Early Modern England 1485-1714: A Narrative History (7 page)

Read Early Modern England 1485-1714: A Narrative History Online

Authors: Robert Bucholz,Newton Key

Below this level, the country was dotted by numerous market towns ranging in population from a few hundred to one thousand. Abingdon, then in Berkshire, and Richmond in Yorkshire are good examples. Such towns served relatively small rural areas, perhaps 6 to 12 miles in radius. Here, farmers would bring surplus grain or carded wool to sell to merchants who would see to its wider distribution. These towns were not very urban: they consisted of only a few streets, a market square, and the surrounding land, which most townsmen farmed to supplement their income from trade. On market days and some holy days their populations would swell. Otherwise we would barely recognize them as towns.

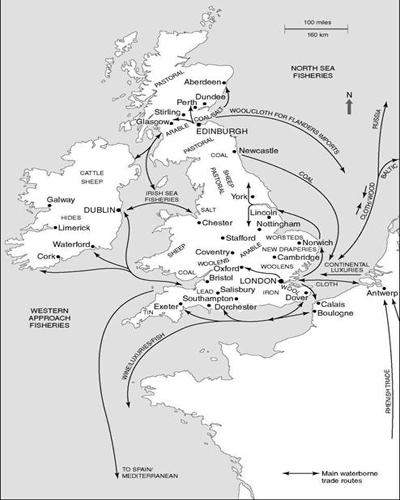

Map 3

Towns and trade

.

Most English men and women lived in the countryside – not in cities or even towns, but in settlements of, perhaps, 50 to 300 people. Let us imagine that, in our quest to know the English people in 1485, we have undertaken to meet them in their natural habitat, the English village. Admittedly, villages would be few and far between in this still underpopulated country, especially in the North, West Country, and East Anglia, where most people lived in more isolated settlements. If we sought out the greatest concentration of villages, in the southeast, we would notice, first, a belltower, probably Norman in style, indicating a church (see

plate 1

). In fact, the only buildings of note, probably the only ones built of stone, would be this church, a grain mill, and, perhaps, the manor house of the local gentleman or lord. The church reminds us of the centrality of religion and parish life to the villagers in 1485; the mill reminds us of the importance of grain-based agriculture; and the manor house, of a social hierarchy based on who owned land and who did not.

The church’s denomination would be what we would today call Roman Catholic; the Reformation was a half-century in the future and no other faiths were tolerated.

8

If we were to watch, unobserved, for a week or a month, we would see a parade of villagers pass through its doors not only on Sunday morning, or even on holidays, but on weekdays as well. For the church was not only the religious center of the village but its social center. Many villagers belonged to guilds and fraternities dedicated to particular saints or devotions or charities. Later, when pews were added in the sixteenth century, where a family sat or kneeled indicated its relative status in the community, the most prominent near the altar at the east end, the less important towards the back. Christenings, weddings, and funerals – that is, every important rite of passage – were commemorated here. Villagers also centered their celebrations of holidays (“holy days”) at the church. By the late medieval period some 40 such annual holidays interrupted the work week. On Sundays and “holy days,” all gathered at the church to hear mass (in Latin) and a homily (in English), during which congregants not only received spiritual instruction but also heard from the priest all the “official” news which the king, the bishop, or the landlord wanted them to know. After all, in 1485 there were no newspapers, no radio, no television. The monarch’s proclamations were printed, but often in the hundreds or, at most, in the several thousands, hardly enough to blanket the country’s 9,000-plus parishes. In any case, the vast majority of the rural population was illiterate. The Sunday sermon was, apart from the occasional traveler, the only source of outside news. After mass, there was likely to be a “church ale” in the church hall or village common at which villagers ate, drank, played sports like camp ball or stoolball (forerunners of football/soccer and cricket), chatted up members of the opposite sex, and shared the unofficial news purveyed in village rumor and gossip.

Plate 1

Diagram of an English manor. The Granger Collection, New York

.

After the excitement of the day, the villagers would return to their homes. A more substantial villager, say a yeoman, would live in a stone farmhouse in the North, a wooden one in the South. But at the end of the Middle Ages most villagers lived in one- and two-room huts or shacks, made of “wattle and daub” – essentially, mud, animal manure, straw – anything that would hold together within a timber frame.

9

They had one wooden door and few windows – for windows let in the cold. These would be covered by thin horn or greased paper. If we were to enter one of these hovels, it would take our eyes some time to adjust to the darkness, first because of the lack of windows, and second because, in the center of the beaten mud floor, would be a smoking hearth. This would be the family’s main source of heat and implement for cooking. Its smoke was vented through a hole in the thatched roof. Looking about the room, there might be a few pots and pans, some tools, a candle holder with some candles, a chest, a table and a few stools, and some articles of clothing. Bags of flock or straw served as mattresses. The entire family lived in these one or two damp, drafty rooms with very little privacy from each other and, often, but a thin wall to separate them from their livestock. This would consist of perhaps a cow, certainly a sheep. The milk, cheese, wool, and, very occasionally, meat they provided would be crucial to keep the family fed and solvent, especially during bad times. Conversely, the death of the family’s animals could spell economic disaster, so it was as important to shelter them as it was to house the family itself.

Prior to the period of time covered by this book, during the Middle Ages, these villagers would likely have been serfs, that is, unfree laborers who held land from their landlord in exchange for work on his estate. But, in an ironic twist, the Black Death which had been so destructive of human life had broken the chains of serfdom for those who had survived. That is, the dramatic fall in population which followed the epidemic had led to a labor shortage at the end of the fourteenth century. The peasants who were left alive, sensing their advantage, began to demand their freedom from serfdom and their pay in wages. So few peasants remained to do the work of the manor that, if their landlord refused to make concessions, they could always leave him for a master who would do so. At first, medieval landlords resisted. But in the end, the law of supply and demand, which few in the Middle Ages understood and no one had yet named, worked as inexorably on labor as it does on products: peasants were able to commute their serfdom into freedom, their work into wages, to be partly paid back to the landlord in rent. By 1485 most villagers were free tenant farmers; that is, they rented from a great landlord who owned the manor upon which the village was built. The villagers, unlike serfs, were able to leave this relationship if they wished. This forced landlords to try to keep their old tenants or attract new ones by increasing wages and lowering rents: since the time of the Black Death laborers’ wages had doubled from 2 pence a day to 4, while rents in some areas had fallen from the beginning of the century by as much as one-third.

If we had chosen to visit a small hamlet in the rugged North or a fenland (swamp) settlement in East Anglia, the local people might make their living through pastoral (i.e., sheep or dairy) farming; spinning wool, flax or hemp; quarrying; and, of course, poaching in the king’s woods. Those on the coasts survived on fishing and trade. But most villagers in the southeast relied on arable (crop) farming. Near the village would be a plot of common land, where villagers’ animals could be grazed; and individual strips of land, farmed by each tenant (see

plate 1

). Late medieval farmers and estate managers knew about soil depletion and the need for crop rotation, so these strips would be grouped in three different fields. At any given time, one would hold an autumn crop, such as wheat; a second would hold a spring crop, such as oats or barley; and a third would lie fallow. The big tasks of medieval farming – plowing, sowing, and harvesting – would be organized communally, which means that the whole village, including its women and children, participated. Work lasted from sun-up to sun-down, which meant longer hours in summer, shorter hours in harsher conditions in winter. When not aiding their husbands and fathers in the fields, women cooked, sewed, and fetched water. Older children helped by looking after the family’s smaller children and animals. As we have seen, milk and wool could be sold for a little extra income. Another way to make extra money was to turn one’s dwelling into a “public house,” or “pub,” by brewing ale (traditionally a woman’s role).

Perhaps in the center of the manor, perhaps on a hill overlooking the village, perhaps many miles away on another of the landlord’s estates, would be his manor house. He might have been a great nobleman or a gentleman. He might have owned and lived on this one estate, or have owned many manors and lived at a great distance. What is certain is that his control of the manor gave him great power over the villagers. First, the landlord owned most of the land in the neighborhood, apart from that of a few small freeholders. This provided him with a vast income from harvesting crops grown upon it, from mining minerals within it, and, above all, from collecting rents from the tenants who inhabited it. The landlord was also likely to own the best – and often the only – mill for grinding grain and oven for baking it. This provided another means to extract money from his tenants. Control of the land also gave him control of the local church, for he probably named the clergyman who preached there, a prerogative known as the right of

advowson

. He had the further right to call on the services of his tenants in time of war. His local power might lead the king to name him a local sheriff or

justice of the peace (JP)

. This meant that he was not only the king’s representative to his tenants but their judge and jury for many offenses as well. His local importance might, paradoxically, require him to spend time away from his estates, in London. If he were a peer, he sat in the upper house of Parliament, the House of Lords, and acted as a crucial link between the court and his county. If he were a particularly wealthy gentleman (or the son of a living peer) he might be selected by his fellow landowners to sit in the lower house, the House of Commons. One of the few sets of records allowing us insight into a landowning family during the fifteenth century,

The Paston Letters

, shows how little time the Paston men actually spent on their estates in the country (in this case, Norfolk), and how much more of it they spent in London.

10

Admittedly, the same forces which had improved the lot of their tenants were compromising the wealth and power of the landed orders at the end of the Middle Ages. The decline in population had led to reduced demand for the food grown on their land. This produced a fall in prices which cut into their profits. Those profits were further compromised by the high wages that landlords now had to pay to hold onto their tenants. As a result, landowners increasingly abandoned

demesne

farming (that is, relying for profit on the sale of crops grown on that portion of the estate not being rented out) entirely in favor of renting nearly all their land to peasants, who paid a cash rent. These rents, not the food grown, eventually became the chief source of profit to great landowners. But, as we have seen, low population also forced landlords to keep rents low, once again to avoid losing their tenants. So, some landowners went further, abandoning crop farming entirely in favor of sheep farming, which was far less labor-intensive and more predictable, since it was less dependent on the weather. This process, called

“enclosure”

from the need to erect fences across otherwise open farmland in order to restrain sheep, was highly controversial precisely

because

it was less laborintensive. Contemporaries feared that tenants who had previously farmed the land would be thrown off it, thus losing both their jobs and their homes. The Church preached against enclosure, Parliament legislated against it, and socially conscious writers, most notably Sir Thomas More (1478–1535) in

Utopia,

complained that whole villages were being depopulated because of hungry sheep and greedy owners. Historians now question how many peasants were actually thrown off the land, since it had already been depopulated by the Black Death. Rather, enclosure was a strategy for keeping land profitable when there was no one to work it. But in some areas, such as the rich, arable Midlands, extensive enclosure in the sixteenth century did lead to real social problems. In any case, neither legislation nor propaganda was effective in stopping enclosure when a landlord had a mind to do it.