Early Modern England 1485-1714: A Narrative History (3 page)

Read Early Modern England 1485-1714: A Narrative History Online

Authors: Robert Bucholz,Newton Key

Thinking about historical characters as real people faced with real choices, fighting real battles, and living through real events should help you to make sense of the connections we make below and, we hope, to see other connections and distinctions on your own.

The following text is, for the most part, a narrative, with analytical chapters at strategic points to present information from those subfields (geography, topography, social, economic, and cultural history) in which many of the most recent advances have been made, but for which a narrative is inappropriate. That narrative largely tells a story of English politics, the relations between rulers and ruled, in the Tudor period (1485–1603, chapters 1–5) and the Stuart period (1603–1714, chapters 7–10). Chapter 1 includes a brief narrative of the immediate background to the accession of the Tudors in 1485, the Conclusion, a few pages on the aftermath of Stuart rule from 1714. We believe, and hope to demonstrate, that the political developments of the Tudor–Stuart period have meaning and relevance to all inhabitants of the modern world, but especially to Americans. We also believe that a narrative of those developments provides a coherent and convenient device for student learning and recollection. Finally, because we also think that the economic, social, cultural, religious, and intellectual lives of English men and women are just as important a part of their story as the politics of the period, we will remind you frequently that the history of England is not simply the story of the English monarchy, or its relations with Parliament. It is also the story of every man, woman or child who lived, loved, fought, and died in England during the period covered by this book. Therefore, we will stop the narrative to encounter those lives at three points: ca. 1485 (Introduction), 1603 (chapter 6), and 1714 (Conclusion).

In order to provide a text which is both reader-friendly and interesting, we have tried to deliver it in prose which is clear and, where the material lends itself, not entirely lacking in drama or humor (with what success you, the readers, will judge). In particular, we have tried to provide accurate but compelling accounts of the great “set pieces” of the period; quotations which will stand the test of memory; and examples which enliven as well as inform while avoiding as much as possible the sort of jargon and minutiae that can sometimes put off otherwise enthusiastic readers. Again, this is all part of a conscious pedagogical strategy born of our experience in the classroom.

That experience has also caused us to realize the importance of “doing history”: of students and readers discovering the richness of early modern England for themselves through contemporary sources; making their own arguments about the past based on interpreting those sources; and, thus, becoming historians (if only for a semester). For that reason, we have also assembled and written a companion to this book entitled

Sources and Debates in English History, 1485–1714

(also published by Blackwell). The preface to that book indicates how its specific chapters relate to chapters in this one (see also chapter notes at the end of this book).

A word about our title and focus. One might ask why we called our book

Early Modern England,

rather than

Early Modern Britain?

After all, one of the most useful recent trends in history has been to remind us that at least four distinct peoples share the British Isles and that the English “story” cannot be told in isolation from those of the Irish, the Scots, and the Welsh. (Not to mention continental Europeans, North Americans, Africans, and, toward the end of the story, Asians as well.) We agree. For that reason the text contains significant sections on English involvement with each of the Celtic peoples (as well as some discussion of England’s relationship to the other groups noted above) in the early modern period, all of which are vital for our overall argument. But we believe that it is the English story that will be of most relevance to Americans at the beginning of the twenty-first century. We believe this, in part, because it was most relevant to who Americans were at the beginning of their

own

story, in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. We would argue, further, that English notions of right and proper behavior, rights and responsibilities, remain central to national discourse in both Canada and the United States today. Important as have been the cultural inheritance of Ireland, Scotland, and Wales to Americans, the impetus for the inhabitants of each of these countries to cross the Atlantic was always English, albeit often oppressive. Moreover, brutal and exploitative as

actual

English behavior has often been toward these peoples, the

ideals

of representative government, rule of law, freedom of the press, religious toleration, even a measure of social mobility, meritocracy, and racial and gender equality which some early modern English men and women fought for and which the nation as a whole slowly (and often partially) came to embrace, are arguably the most important legacy to us of any European culture.

Finally, as in our own classes, we look forward to your feedback. What (if anything!) did you enjoy? What made no sense? Where did we go on too long? Where did we tell you too little? Please feel free to let us know at earlymodernengland@ yahoo.com. In the meantime, there is an old, wry saying about the experience of “living in interesting times.” As you will soon see, the men and women of early modern England lived in

very

interesting times. As a result, exploring their experience may sometimes be arduous, but we anticipate that it will never be dull.

Robert Bucholz

Newton Key

Acknowledgments

No one writes a work of synthesis without contracting a great debt to the many scholars who have labored on monographs and other works. The authors are no exception; our bibliography and notes point to some of the many historians who have become our reliable friends in print if not necessarily in person. We would also like to acknowledge with thanks our own teachers (particularly Dan Baugh, the late G. V. Bennett, Colin Brooks, P. G. M. Dickson, Clive Holmes, Michael MacDonald, Alan Macfarlane, the late Frederick Marcham, and David Underdown), our colleagues, and our students (whose questions over the years have spurred us to a greater clarity than we would have achieved on our own). A special debt is owed to the anonymous readers for the press, whose care to save us from our own errors is much appreciated – even in the few cases where we have chosen to persist in them. We have also benefited greatly from our attendance at seminars and conferences, most notably the Midwest Conference on British Studies, and from hearing papers given by, among others, Lee Beier, Ethan Shagan, Hilda Smith and Retha Warnicke. For advice, assistance, and comment on specific points, we would like to thank Andrew Barclay, Fr. Robert Bireley, SJ, Barrett Beer, Mary Boyd, Regina Buccola, Eric Carlson, Erin Crawley, Brendan Daly, Carolyn Edie, Gary DeKrey, David Dennis, Alan Gitelson, Bridget Godwin, Michael Graham, Mark Fissel, Jo Hays, Roz Hays, Caroline Hibbard, Theodore Karamanski, Carole Levin, Kathleen Manning, Eileen McMahon, Gerard McDonald, Marcy Millar, Paul Monod, Philip Morgan, Matthew Peebles, Jeannette Pierce, James Rosenheim, Barbara Rosenwein, James Sack, Lesley Skousen, Johann Sommerville, Robert Tittler, Joe Ward, Patrick Woodland, Mike Young, Melinda Zook, and the members of H-Albion. We are grateful for the support, advice, and efficiency of Tessa Harvey, Brigitte Lee, Angela Cohen, Janey Fisher, and all the staff at Wiley-Blackwell. We have also received valuable feedback from students across the country and, in particular at Dominican University, Eastern Illinois University, Loyola University, the University of Nebraska, and the Newberry Library Undergraduate Seminar. Our immediate family members have been particularly patient and accommodating. We would especially like to thank Laurie Bucholz for keeping this marriage (not Bob and Laurie but Bob and Newton) together. For this, and much more besides, we thank them all.

Conventions and Abbreviations

| Citations | Spelling and punctuation modernized for early modern quotations, except in titles cited. |

| Currency | Though we refer mainly to pounds and shillings in the text, English currency included guineas (one pound and one shilling) and pennies (12 pence made one shilling). One pound ( £ ) = 20 shillings (s.) = 240 pence (d.). |

| Dates | Throughout the early modern period the English were still using the Julian calendar, which was 10–11 days behind the more accurate Gregorian calendar in use on the continent from 1582. The British would not adopt the Gregorian calendar until the middle of the eighteenth century. Further, the year began on March 25. We give dates according to the Julian calendar, but assume the year to begin on January 1. Where possible, we provide the birth and death dates of individuals when first mentioned in the text. In the case of monarchs, we also provide regnal dates for their first mention as monarchs. |

| BCE | Before the common era (equivalent to the older and now viewed as more narrowly ethnocentric designation BC, i.e., Before Christ). |

| BL | British Library. |

| CE | Common era (equivalent to AD). |

| Fr | Father (Catholic priest). |

| JP | Justice of the peace (see Glossary). |

| MP | Member of Parliament, usually members of the House of Commons. |

Introduction: England and its People, ca. 1485

Long before the events described in this book, long before there was an English people, state, or crown, the land they would call home had taken shape. Its terrain would mold them, as they would mold it. And so, to understand the people of early modern England and their experience, it is first necessary to know the geographical, topographical, and material reality of their world. Geography is, to a great extent, Destiny.

This Sceptered Isle

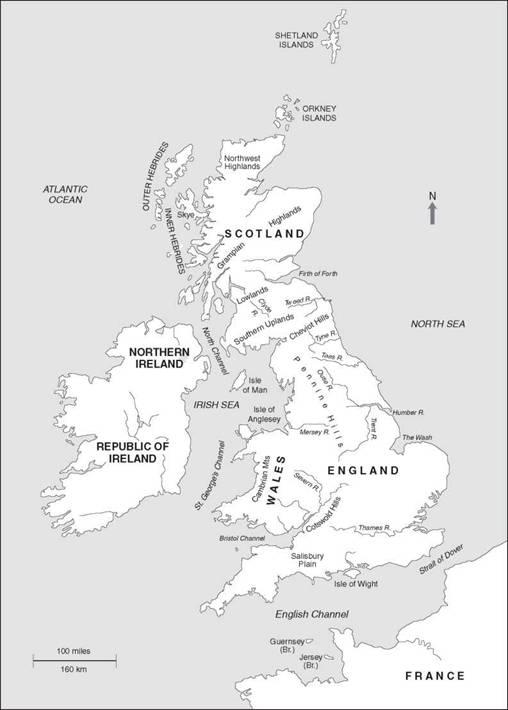

The first thing that most non-British people think that they know about England is that it is an island. In fact, this is not strictly true. England is, rather, the southern and eastern portion of a group of islands (an archipelago) in the North Sea known as the British Isles (see

map 1

). While the whole of the archipelago would be ruled from London by the end of the period covered by this book, and while the terms “Great Britain” and “British” have, at times, been applied to that whole, it should never be forgotten that the archipelago is home to four distinct peoples, each with their own national histories and customs: the English, the Irish, the Scots, and the Welsh.

1

This book will concentrate on the experience of the first of these peoples. But because that experience intertwines with that of the other three, the following pages address their histories as well.

While the English may share their island, they have always defined themselves as an “island people.” That fact is crucial to understanding them, for an “island people” are bound to embrace an “island mentality.” One place to begin to understand what this means is with a famous passage by England’s greatest poet, William Shakespeare (1564–1616):

This royal throne of kings, this sceptr’d isle,

This earth of majesty, this seat of Mars,

This other Eden, demi-paradise:

This fortress built by Nature for herself

Against infection and the hand of war;

This happy breed of men, this little world,

This precious stone set in the silver sea,

Which serves it in the office of a wall,

Or as a moat defensive to a house,

Against the envy of less happier lands:

This blessed plot, this earth, this realm, this England. (

Richard II

2.1)

Map 1

The British Isles (physical) today

.