Early Modern England 1485-1714: A Narrative History (31 page)

Read Early Modern England 1485-1714: A Narrative History Online

Authors: Robert Bucholz,Newton Key

Once again, a demand from Scotland posed a dilemma for the English queen. On the one hand, Mary was a kinswoman and a fellow monarch, unjustly deposed by her subjects. On the other hand, she was an accused murderess, a Roman Catholic, and, because of her Tudor blood and Elizabeth’s childlessness, the next heir to the English throne. Elizabeth remembered full well the destabilizing role that she, as princess and heir, had played under Mary Tudor. As she said, “I know the inconstancy of the people of England, how they ever mislike the present government and have their eyes fixed upon that person that is next to succeed.”

10

It was inevitable that Mary Queen of Scots would play the same role under Queen Elizabeth – with two added twists. First, if the religious and diplomatic situation of England deteriorated, plots in her favor might well receive the support of the pope and the Catholic powers. Second, Mary might not be as discreet as Elizabeth had been: given her impulsive nature, there was every reason to believe that she, too, would give active support to any scheme to put her on the English throne. In the end, one of these two women would have to go. The catalyst for that choice would come from Spain.

England and Spain

The situation of the great Catholic powers was more complicated, with regard to England, than might at first appear. For most of the sixteenth century, France had been England’s most consistent and dangerous enemy. Just as English kings had tried to use their base at Calais to aggrandize French territory, so the French had used their Scottish allies to threaten English sovereignty. But by 1568 Scotland was more or less under the control of a Protestant government at peace with England; while France was about to enter a long period of religious and political instability. First, a series of sickly boy-kings of the Valois family ascended the throne, to be controlled, fitfully, by their mother, the Catholic queen regent Catherine de’ Medici (1518–89). As the Valois line dwindled to a weak conclusion under Henry III (1551–89; reigned 1574–89), two other families emerged to challenge for power in France, the Catholic Guises and the Protestant Bourbons. Although France remained a Catholic country, there was an important Huguenot (Calvinist-Protestant) minority, especially in the south and among the noble and merchant classes. Catholics and Protestants fought not only over who should succeed to the French throne after Henry III, but also over whether Huguenot Protestantism should be tolerated at all. That struggle took a dramatic and violent turn on August 24, 1572, St. Bartholomew’s Day, when Catholics launched a surprise massacre of Protestants in Paris. This event affected England in two ways. First, it left France even more bitterly divided than before on the questions of the succession and religious toleration. The ensuing civil conflicts, called the Wars of Religion, eliminated the French threat to England for a generation. Second, the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre provided yet more evidence, in English eyes, of Catholic treachery and cruelty.

Spain was another matter. Thanks to the Habsburg–Tudor alliance that dated back to Henry VII and Ferdinand and Isabella, England and Spain had generally been partners in earlier sixteenth-century conflicts. The Anglo-Spanish alliance, renewed by Mary, survived even the more-or-less Protestant religious settlement of 1559: so long as France remained strong and aggressive, Spain relied on England to help protect its valuable possessions in the Netherlands. But as the French began to decline into disunity and Spanish power grew in the 1560s, cracks began to appear in the edifice of Anglo-Spanish friendship.

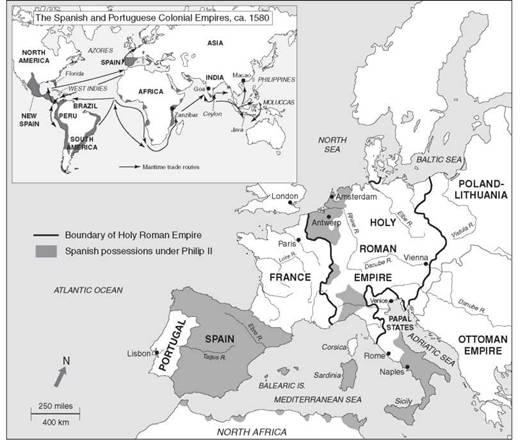

England and Spain divided in part because of the very wealth and power that otherwise made the Spanish such attractive allies. Thanks to the Habsburg genius for advantageous marriages, the discoveries of Columbus, and the conquests of captains like Hernán Cortez (1485–1547) and Francisco Pizarro (ca. 1471–1541), Philip II ruled an empire that included not only Spain but most of Southern Italy, the Netherlands, and all of Central and South America, apart from Portuguese Brazil (see

map 8

). That empire supplied the Spanish government with vast wealth, mostly in the form of Mexican and Peruvian silver, mined by Native American and (increasingly) African slaves, and transported across the Atlantic in biannual treasure fleets. This wealth paid for the greatest army in Europe. Elizabeth’s government worried that, given Philip’s devout Catholicism, he might, sooner or later, be tempted to use these resources to take advantage of the presence of Mary Queen of Scots in England. Philip’s government worried that, given the wealth and vulnerability of his empire, English mariners might, sooner or later, be tempted into piracy.

Map 8

Spanish possessions in Europe and the Americas.

In fact, every European power looked greedily upon the Spanish Empire and its trade monopoly. But English sailors actually took steps to break into it. One way to do that was to acquire and sell African captives to Spanish landowners in the New World, who would employ them in slave labor. In 1568 Spanish vessels attacked a “peaceful” English slaving fleet, commanded by John Hawkins (1532–95) and secretly authorized by Queen Elizabeth, at San Juan de Ulúa in the Caribbean. Only two English ships escaped: Hawkins’s and one commanded by a young mariner named Francis Drake (1540–96). Allowing Drake to escape was a big mistake, for he would forever after harbor a deep hatred against Spain. That hatred was fanned by stories that the Inquisition brutally mistreated captured English Protestants, and often sentenced them to hellish conditions as oarsmen in Spanish Mediterranean galleys. (The poetic justice that those conditions were just deserts for the atrocities committed on their African slave cargoes was, of course, lost on all concerned.)

As we shall see, Elizabeth responded to the incident of 1568 by confiscating Spanish ships which blew into English ports and by turning a blind eye to the piracy of men like Hawkins, Drake, and Sir Martin Frobisher (1535?-94). She even granted them privateering commissions which, in effect, allowed them to make their own personal war on the Spanish seaborne empire. Sometimes she invested in their voyages, as did Leicester, Walsingham, and other important courtiers. In 1573

El Draque

(the dragon), as the Spanish called him, daringly raided the isthmus of Panama, netting a cargo worth the phenomenal sum of

£

20,000.

11

In 1577–80 he grew even bolder, sailing his ship, the

Golden Hind,

across the South Atlantic to the east coast of South America, through the Straits of Magellan, up the west coast as far north as California, across the Pacific, around the Cape of Good Hope, and back north to England – plundering Spanish shipping, raiding Spanish towns, and reading to his crew from Foxe’s

Book of Martyrs

all along the way. They became only the second expedition (Ferdinand Magellan, 1480–1521, had commanded the first) and the first Englishmen to circumnavigate the globe. Not that Drake could be sure of a hero’s welcome upon his return: arriving at Plymouth in September 1580, he is said to have asked local fishermen if the queen still lived. If Elizabeth had died and Mary Queen of Scots had succeeded her while he was away, his adventure would have been viewed as piracy and his life and treasure forfeit. But the queen did still live. That spring she knighted him on the deck of the

Golden Hind

– and claimed her cut of treasure, at least

£

264,000. Of course she did this more or less in secret. Publicly, she denounced the depredations of her sailors just as a modern state sponsor of terrorism might do.

Philip knew better, but, in the interest of peace (and the increasingly distant hope that Elizabeth might die or declare herself a Catholic), he decided that Spain could afford to absorb these occasional English pinpricks. The second area of conflict between the two nations was far more serious: Spain’s holdings in the Netherlands (see also

map 9

, p. 143). Charles V had given the Netherlands to Philip, his son, in 1554; two years later Philip ascended the throne of Spain. Despite Spanish-Catholic rule, much of the Low Countries had been attracted to Calvinist Protestantism. In 1566 a group of Dutch and Flemish noblemen, both Catholic and Protestant, led by William of Orange (1533–84, also known as “William the Silent”), formed a league to oppose Spanish influence and, in particular, any future imposition of the Spanish Inquisition on the Netherlands. The following year, Philip attempted to do just that, sending Fernando Alvarez de Toledo, duke of Alva (1508–83), and 20,000 troops to ensure order. Instead, the arrival of the Inquisition backed by the occupying army incited a revolt against Spanish rule which would drag on for decades.

Once again, Elizabeth faced a dilemma. Should she support Philip as her ally and fellow monarch and, in so doing, allow the Dutch rebels to wither away? Or should she support her fellow Protestants, and risk undermining the Great Chain of Being, disrupting trade, and inviting war with Spain? Toward the end of 1568 she was pushed to a decision after bad weather and privateers forced a Spanish fleet carrying

£

85,000 in gold bullion for Alva to shelter in English ports. The Spanish, assuming that Elizabeth would seize the bullion, arrested the English merchants trading in the Netherlands and impounded

their

ships and goods. This, combined with the news of the attack on Hawkins’s fleet noted above, gave the queen an excuse to fulfill Spanish expectations by confiscating the bullion in retaliation. It should be obvious that rising levels of distrust and duplicity between the two powers were destroying their alliance, despite the absence of overt acts of war. Henceforward, the queen secretly supplied the rebels with money and offered a safe haven in English ports to Dutch privateers, known as “the sea-beggars.” In public, she condemned the revolt just as modern states do when they fund proxy wars. Philip was not fooled. In response, he closed the port of Antwerp, England’s main cloth entrepôt in Europe, for five years. He did not want war any more than Elizabeth did, but events seemed to be moving in that direction. In any case, the presence of a Catholic minority and, from 1568, a Catholic heir in England meant that two could play at Elizabeth’s game: Philip II began to wage a secret war of his own.

Plots and Counter-Plots

In the late 1560s the pope began to encourage an English Catholic revival. As we have seen, the Roman Catholic Church had responded slowly to the Reformation. That response, sometimes referred to as the Counter-Reformation, was formulated at the Council of Trent, which met, on and off, from 1545 to 1563 in Trent, Italy. This assemblage of churchmen pursued a thorough inquiry into Catholic dogma and practice. In the end, it rejected most of Luther’s doctrinal and structural criticisms of Catholicism. It reaffirmed the efficacy of the seven sacraments and good works, transubstantiation, Purgatory, even the granting of indulgences. Organizationally, it reasserted the authority of the pope and bishops and the sanctity and celibacy of the priesthood. On the other hand, the council tacitly conceded Luther’s point about corrupt churchmen. It called for reforms of pluralism, absenteeism, and in the education and behavior of priests. The establishment of the Society of Jesus, or Jesuits, in 1540 is yet another sign of the Church’s desire to reinvent itself. This order of priests, supremely well educated and organized according to military discipline by a former soldier, Ignatius of Loyola (1491–1556), was well equipped to engage in theological controversy, preaching, missionary and pastoral work in order to combat what Catholics saw as Protestant heresy. And they targeted England.

By the late 1560s, the small group of English Catholic priests who refused to conform to the new religious settlement was dying out – and so was Roman Catholicism. In 1568 Fr. William Allen, a Catholic exile (1532–94), sought to remedy the shortage of priests by founding a seminary for the training of English Catholic clergy at Douai, France. In 1579 the Jesuits founded another such seminary at Rome. From the mid-1570s a steady stream of seminary priests began to filter back into England and Wales. In 1580, Allen arranged the first Jesuit mission to England in the persons of Frs. Edmund Campion (1540–81) and Robert Persons (1546–1610). Their avowed purpose was to maintain the preaching and teaching of Catholic doctrine in order to preserve the English Catholic minority in its faith, not to convert Protestants, nor to foment rebellion against Elizabeth. But the actual record of these early missionary efforts is ambiguous. In the 1560s and 1570s the largest concentrations of Catholics in England were to be found in the remote North and Welsh Marches, often among fairly isolated and humble communities. Yet, the seminary priests concentrated their activities in the Southeast, ministering to aristocratic Catholic families who could provide a chapel and, if needed, a place to hide. They seem to have believed that the only hope for a Catholic restoration lay with the powerful and wealthy gentry of the South, not the peasants of the North and West. This may help to explain, first, why Catholicism continued to die out among the general populace and, second, why these religious missionaries soon found themselves embroiled in plots against the throne.