Early Modern England 1485-1714: A Narrative History (27 page)

Read Early Modern England 1485-1714: A Narrative History Online

Authors: Robert Bucholz,Newton Key

Most of Mary’s advisers and many of her subjects seem to have wanted her to marry an English peer. But the queen, wanting to solidify England’s place in the Catholic and European world, more comfortable with her Spanish heritage than her English roots, chose, instead, her cousin, the son of the Holy Roman emperor and heir to the Spanish Empire, Philip, king of Naples (1527–98; reigned in Naples from 1554, in Spain from 1556). This choice was immediately opposed by most of the Privy Council and Parliament. More ominously, it seemed to be unpopular with Mary’s people as well. In January 1554 Sir Thomas

Wyatt

(1521?–54) led 3,000 men, mostly from Kent, toward London. Their goal was, at the very least, to prevent the Spanish marriage and, possibly, to displace Mary in favor of her younger sister, Elizabeth. Lacking an army of her own, Mary appealed to her subjects’ loyalty in an eloquent speech at London’s Guildhall, rallied the royal guards, and crushed the rebels. Wyatt and about 90 followers were executed. So were Lady Jane Grey and Guildford Dudley, for their very existence was thought to incite rebellion. Princess Elizabeth also came under suspicion and was lodged in the Tower. But Elizabeth had been careful to avoid overt involvement in the plot or to leave evidence of disloyalty to her sister, and so Mary felt her hands tied. Still, the new queen had demonstrated characteristic Tudor tenacity and ruthlessness in the first major crisis after her accession. In the end, like a good Tudor, she got her own way. The marriage to Philip took place at Winchester Cathedral in July 1554. Her next move, the restoration of Catholicism, would be even more controversial and difficult to accomplish.

Catholic Restoration

The break with Rome had come through parliamentary legislation. The mending, if it was to have any popular support or long-term success, would also require parliamentary cooperation. But the nobles and gentlemen who sat in Parliament had a great deal to lose by such a restoration: all their lovely and profitable monastic lands. In October 1553 that assembly agreed to revoke the religious legislation of the previous reign. Gone were the Prayer Book and Act of Uniformity. But Parliament would do nothing positive to restore Catholicism until they knew what was to become of the monastic lands. In 1554 Reginald, Cardinal Pole (1500–58), an English Catholic exile, returned from the continent to serve as both papal legate and Mary’s chief religious adviser. He negotiated an agreement whereby the pope granted a dispensation allowing their present owners to keep the monastic lands. In return, Parliament consented to reunite with Rome and reenacted the heresy laws in January 1555. Thus the pope’s concession on monastic lands allowed Mary to achieve her immediate goal of parliamentary restoration of Roman Catholicism as the state religion of England. But in the long term it meant that the dissolved monasteries, convents, almshouses, schools, and hospitals – the most attractive and socially significant side of institutional Catholicism – would not be restored. Mary encouraged the new founding of such establishments, but a shortage of money and time on the throne limited her success. The institutional presence of the Catholic Church would never recover.

In its absence, all Mary could do was to restore previously deprived Catholic bishops like Gardiner and Tunstall, mandate the revival of Catholic worship in churches, require her subjects to attend mass on Sunday, and persecute those who refused to comply. In fact, the Marian restoration of Catholicism did achieve some success. Many churches, particularly in remote areas, had failed to embrace Protestant reform, or had stored or buried their rood crosses and screens, statues, and images in anticipation of Catholic revival. Many English men and women returned to the old ways eagerly, or at least without a murmur.

But others did not. Devoted Protestants, or those for whom Catholic practices were new, strange, or threatening, would not cooperate. Mary responded, first, by purging the universities and the clergy of Protestants. She ejected some 2,000 priests for preaching Protestant ideas or, more usually, for taking wives: the latter was virtually the only clear, outward sign of Protestantism. This amounted to about one-quarter of the priesthood, a deficit which Catholic seminaries on the continent could not soon fill. Some of the displaced clergy joined the 800 men and women who fled abroad to Protestant centers such as Frankfurt and Geneva, where they imbibed reformist ideas at the source and waited for the next reign. For those Protestants – clergy or laymen – who could not leave and would not recant, Mary and Pole had one last remedy: burning at the stake. They began on February 4, 1555 with John Rogers, a translator of the Bible into English. They continued in Oxford with the burning of three prominent Protestant clergymen: Hugh Latimer, bishop of Worcester (ca. 1485–1555), and Nicholas Ridley, bishop of London (ca. 1502–55), in October; and Archbishop Cranmer in March 1556. It is said that, as the fires were being lit, Latimer called out: “be of good comfort, Master Ridley, and play the man. We shall this day light such a candle, by God’s grace, in England, as I trust shall never be put out.”

8

But clergymen were only the most prominent victims. Mary’s regime burned 237 men and 52 women as heretics, mostly at Smithfield market, London in just under four years. Some were mere adolescents; the majority came from humble backgrounds, which rendered the burnings even less popular than they would otherwise have been. The Spanish ambassador warned, ominously, that the fires of Smithfield would prove a public relations nightmare for the Catholic side.

And so it has proved. Mary’s burning of nearly three hundred of her subjects for their religious beliefs cannot help but strike the sane modern observer as barbaric. But the operative word in the above sentence is “modern.” Mary and most of her contemporaries thought differently from us. Few would have understood the idea that two individuals could disagree about religion and still be both good people and good subjects. Rather, as we have seen, there was a long tradition in England, and in Europe generally, of believing that one’s own religion was the One True Faith; anyone who held opinions at odds with that faith was a heretic, in league with the Devil, and a profound menace to the salvation of other souls. Any ruler who allowed religious pluralism in his realm was acquiescing in his subjects’ eternal damnation and promoting more immediate chaos here on earth: according to the Protestant William Cecil, Lord Burghley (1520/1–98), “that state co[u]ld never be in safety, where there was toleration of two religions.”

9

Once this is understood, Mary’s reasoning becomes clear: she had to cut out the cancer of Protestantism before it spread. To fail to do so would imperil her reign, her religion, and the immortal soul of every man, woman, and child in England. Henry VIII understood this and put Lutherans and others to death. Elizabeth would understand it too, executing about the same number of Catholics as her sister did Protestants. (But she did so reluctantly, mainly for reasons of state, and over a much longer period of time.)

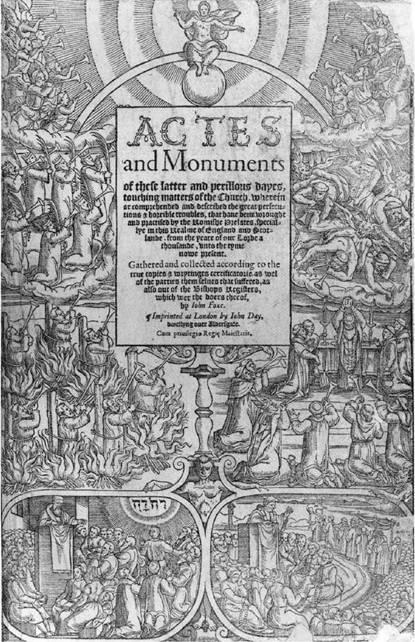

So why do we remember this Tudor as “Bloody Mary”? Because history is written by the victors and Mary’s Catholic restoration would not outlive her brief reign. After her death, the story of the Protestant martyrs would be indelibly imprinted in English religious and historical consciousness, mainly through the writings of John Foxe. Foxe’s

Acts and Monuments,

popularly known as the

Book of Martyrs,

was to be the most popular book in English, after the Bible, for a hundred years. It painted a vivid and lasting picture of martyrs’ courage and “the great persecutions [and] horrible troubles, that have been wrought and practiced by the Romish prelates [bishops]”

10

(see

plate 6

). It thus shaped the black legend of “Bloody Mary” and reinforced the English association of Catholicism with bigotry and cruelty. Take, for example, Foxe’s moving relation of the burning of Archbishop Cranmer. Cranmer was given numerous opportunities to recant his Protestantism. In general, the regime much preferred recantation to execution, especially in Cranmer’s case because he had been the point man for much of Edward’s reformation. Faced with the prospect of death at the stake, the archbishop wavered, agreeing in six separate documents to the papal supremacy and the truth of Roman Catholic doctrine. But when he was brought to St. Mary’s Church on March 21, 1556 to repudiate his Protestantism publicly, he recanted his recantations, saying to the congregation: “[a]nd forasmuch as my hand offended, writing contrary to my heart, my hand shall first be punished there-fore; for, may I come to the fire, it shall be first burned. And as for the pope, I refuse him, as Christ’s enemy, and antichrist, with all his false doctrine.” Foxe continues:

And when the wood was kindled, and the fire began to burn near him, stretching out his arm, he put his right hand into the flame, which he held so steadfast and immoveable (saving that once with the same hand he wiped his face), that all men might see his hand burned before his body was touched. His body did so abide the burning of the flame with such constancy and steadfastness, that standing always in one place without moving his body, he seemed to move no more than the stake to which he was bound; his eyes were lifted up into heaven, and oftentimes he repeated “this unworthy right hand,” so long as his voice would suffer him; and using often the words of Stephen, “Lord Jesus, receive my spirit,” in the greatness of the flame he gave up the ghost.

11

Plate 6

J. Foxe

, Acts and Monuments

title-page, 1641 edition. © British Library Board. All rights reserved

.

Foxe’s vivid accounts of the Protestant martyrs sank deep into the religious, historical, and cultural consciousness of the English people. Given the shortage of Catholic priests, the brevity of Mary’s reign, and her succession by the Protestant Elizabeth, it would be their story which would be remembered. Over the course of the next century, as the English faced Catholic plots at home and invasions from abroad, Foxe’s tales of Mary’s cruelty would convince his readers that God had chosen them to be an elect Protestant nation, defying the infernal power of the cruel Catholic anti-Christ.

But Foxe would have labored in obscurity if Catholicism had won. It might have done so with time. Mary needed a long reign, a Catholic heir, or a powerful ally to provide military support for her counter-reformation. The dénouement of her tragedy was that she failed in the first and fixed her hopes on Spain for the other two.

Foreign Policy and the Succession

Unfortunately, marriage with Philip proved unhappy for both Mary and her subjects. Mary loved her husband and thought it her duty to submit to him. Philip, on the other hand, seems to have seen the marriage as a purely political and diplomatic affair, viewing his wife as his subordinate and her kingdom as community property. Mary, desperate for an heir, experienced a false pregnancy in the winter of 1554–5. In January 1557 Philip, now king of Spain and looking for something else from his marriage, declared war on France, insisting upon England’s support. England, still gripped by economic crisis and lacking a serious military force, was ill-prepared for war. Both Parliament and the Privy Council opposed involvement but Mary, supported by court aristocrats anxious for adventure and ever the dutiful wife, obeyed her husband. In the end, England had nothing to gain and Calais to lose.

The English had once possessed a great empire in France (see

map 5

, p. 35). By 1557 the last tiny outpost of that empire was the port of Calais. Given Parliament’s failure to vote adequate sums of money for the war and Philip’s refusal to divert Spanish troops to help his English allies, it was inevitable that Calais would be taken by the French, who launched a successful surprise attack in January 1558. Calais’s strategic importance was minimal. But psychologically it was crucial, for it was the last reminder of past English greatness on the continent and of their most heroic monarchs’ feats of arms. Its loss was a devastating blow and, for many, a sadly appropriate symbol of Mary’s reign, her blind love for her husband, her Spanish ancestry, and her religion. While this was not entirely fair, legend has it that even Mary herself was haunted by this disaster: according to apocryphal report, she is supposed to have said “when I am dead and opened you will find Calais lying in my heart.”

12