Eclipse (12 page)

Authors: Nicholas Clee

While visitors were arriving in large numbers, Epsom needed to provide more than salty water to keep them amused. It staged athletics competitions, in which the grand folk watched their footmen race. There were concerts and balls, hunting and gambling; and there was horseracing. The first mention of the sport in the local archives is a sad one: the burial notices for 1625 include the name of William Stanley, âwho in running the race fell from the horse and brake his neck'. The next record helps to explain why Oliver Cromwell banned horseracing: in 1648, during the English Civil War, a group of Royalists met on the Downs âunder the pretence of a horse race ⦠intending to cause a diversion on the King's behalf'. The sport got going again immediately after the Restoration, and Charles came, with mistresses, before transferring his sporting activities to Newmarket. A poet called Baskerville recalled a visit by Charles, in lines worthy of the master of bathos William McGonagall:

Next, for the glory of the place,

Here has been rode many a race â

King Charles the Second I saw here;

But I've forgotten in what year.

By the early eighteenth century there were regular spring and autumn race meetings at Epsom. Another piece of doggerel portrays the scene:

On Epsom Downs, when racing does begin,

Large companies from every part come in.

Tag-rag and Bob-tail, Lords and Ladies meet,

And Squires without Estates, each other greet.

Bets upon bets; this man says, âTen to one.'

Another pointing cries, âGood sir, tis done.'

Less polite in tone was this reflection on Epsom and its neighbouring towns:

Sutton for mutton, Carshalton for beeves [cattle],

Epsom for whores, Ewell for thieves.

A rather better writer, Daniel Defoe, also observed the scene: âWhen on the public race days they [the Downs] are covered with coaches and ladies, and an innumerable company of horsemen, as well gentlemen as citizens, attending the sport: and then adding to the beauty of the sight, the racers flying over the course, as if they either touched not or felt the ground they run upon; I think no sight, except that of a victorious army, under the command of a Protestant King of Great Britain, could exceed it.'

55

Epsom had horseracing, gambling and whoring, as well as incursions during race meetings by pleasure-seeking Londoners;

what, Dennis might have reflected if he had used twenty-firstcentury idioms, was not to like? He took lodgings in the town, and looked round for a house to buy.

It would not be his first property. For unclear motives, in 1766 Dennis had bought a house about six miles from the centre of London, in the village of Willesden, paying £110 to a Mr Benjamin Browne. He found his Epsom house, on Clay Hill,

56

some time in 1769, and that year he borrowed £1, 500 against three properties: Clay Hill; a house in Clarges Street, Mayfair, where a Mr Robert Tilson Jean was living; and a house in Marlborough Street, Soho, where Dennis was living, conveniently next door to Charlotte's brothel. Dennis arranged this loan from Mr John Shadwell, giving him in return an annuity of £100; he repaid the sum in 1775. The evidence suggests that he was constantly exposing himself, financially, and that bloodstock purchases and gambling setbacks would occasionally leave him naked. Charlotte, too, was apt throughout her life to get into financial difficulty, although by the end of the 1760s her affairs were thriving. She had opened up a new establishment at a prestigious address off Pall Mall, and she was turning it into the most celebrated serail in London.

Dennis was buying horses as well as property. His name appeared for the first time, as subscriber and owner (and as âDennis Kelly'), in the 1768

Racing Calendar

, the book recording the Turf results of that year. The entry gave no hint of the triumphs to come. Dennis owned a single horse, Whitenose, who ran in a single race (the previously mentioned one at Abingdon), and came last. The winner of the £50 prize was Goldfinder, later to play a small role at the end of Eclipse's career; third was the chestnut filly belonging to William Wildman.

By the time of publication of the 1769

Calendar

, however, Dennis, now sporting his âO', owned Whitenose, Caliban,

Moynealta and Milksop â the horse rejected by her mother and nurtured by hand at Cumberland's stud. Milksop, formerly owned by a Mr Payne, was little, and specialized in âgive-and-take' races, in which weight was allocated on the basis of height. He proved to be a money-spinning purchase. In 1769, he won £50 races at Brentwood, Maidenhead and Abingdon, meeting his only defeat on his home turf at Epsom. He won at Epsom in 1770, and also at Ascot, Wantage and Egham. But by then Dennis owned another horse, who, living up to his name, put the others in the shade.

Eclipse ran his trial against the opponent supplied by Dennis a few days before he was due to contest his first public race. Such trials were common, as a means of getting horses fit and of assessing their abilities. They were popular with the touts â gamblers and their associates who would invade gallops and racecourses in search of intelligence. Sir Charles Bunbury, first head of the Jockey Club and owner of horses who competed against Eclipse, disliked the practice. âI have no notion of trying my horses for other people's information, ' he grumbled.

Trials have gone out of fashion, but the acquisition of inside information never has. Nowadays, journalists and other âworkwatchers' scrutinize horses on the gallops, and stable staff earn a few bob to add to their ungenerous incomes by disclosing news about their charges. This horse is so speedy that he is catching pigeons in exercise, they might report; this one has suffered a setback and will not be fully fit on the day; this one will not be âoff' (primed to do his best) for his next race, but is being laid out for a later contest. By the time horses get to the racecourse, the betting market is well primed, and offers a fair reflection of their chances of success.

One would assume that Dennis, with his gambling interests, wanted to keep this trial quiet. If so, he failed: Eclipse's early biographers report that touts, no doubt members of Dennis's circle, travelled down from London to see Eclipse in action. But, like

Wildman (reputedly) at the Cranbourne Lodge auction, they arrived too late. Scanning the Downs for a chestnut with a white blaze, and unable to spot one, they asked an elderly woman, who was out walking, whether she had seen a race. The woman replied that âshe could not tell whether it were a race or not, but that she had just seen a horse with white legs, running away at a monstrous rate, and another horse a great way behind, trying to run after him; but she was sure he would never catch the white-legged horse, if they ran to the world's end'. The touts returned to the capital. By that evening, the prowess of Eclipse was the talk of Munday's coffee house.

51

The English Triple Crown. Nijinsky was the last horse to achieve this feat.

52

Medley's obituary in the

Gentleman's Magazine

in 1798 stated that the sum had come from the Jockey Club.

53

Dennis would covet today's stud earnings. Fifty guineas, Eclipse's initial fee, is the equivalent of about £6, 000 today. Montjeu's covering fee is 125, 000 euros â and he covers a hundred mares in a season.

54

One local history spoils the story by telling us that Dr Nehemiah Grew of the Royal Society had made the discovery some thirty years earlier.

55

Defoe's lines give you an idea of the atmosphere in which, a few years later, the Protestant Prince William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland, would be greeted as a hero for destroying the Catholic Jacobites.

56

Now West Hill.

O

N WEDNESDAY

, 3

MAY

1769, Dennis O'Kelly set out on horseback for the two-mile journey from Epsom to the racecourse on the Downs. An imposing man in his mid-forties, Dennis wore a thick overcoat, which emphasized his increasing bulk; perched on his bewigged head, above blunt features tending to fleshiness, was a battered tricorn hat. Observers would have sympathized with the beast of burden beneath him. Dennis was on his way to watch the Noblemen and Gentlemen's Plate, a good but not top-class contest open to horses who had not previously won £30, and carrying a £50 prize. He may already have backed Mr Wildman's Eclipse; he certainly fancied that the afternoon would offer further betting opportunities. But his interest in Eclipse would not be satisfied by betting alone.

The racecourse was roughly at the site it occupies today, with a finishing straight running from near Tattenham Corner â the downhill bend on the Derby course â and stretching towards the rubbing-house, now the site of the Rubbing House pub. At about this time, a Frenchman called Pierre-Jean Grosley visited Epsom while researching a book called

A Tour to London (1772), in which he described the scene:âSeveral of the spectators come in coaches, which, without the least bustle or dispute about precedency, were

arranged in three or four lines, on the first of those hills; and, on the top of all, was a scaffolding for the judges, who were to decree the prize.' Some courses, such as Newmarket, were marked by posts. When Charles I visited Lincoln races in 1617, he ordered that rails be set up a quarter of a mile from the finish, âwhereby the people were kept out, and the horses that runned were seen faire'.

57

At Epsom, there were no barriers. The crowd towards the finishing post pressed forward from either side, allowing only a slender passage for the racers. There was no betting ring either, on this or on any other course; gamblers congregated at betting posts, shouting out the prices of horses they were prepared to back or lay. The betting post was Dennis's first port of call.

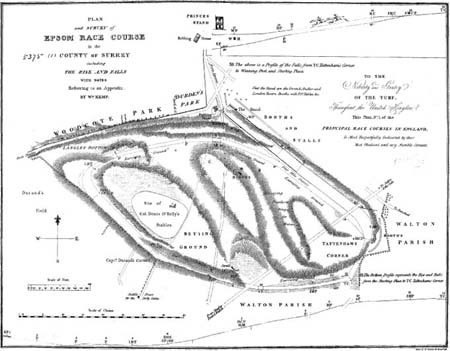

This map of Epsom racecourse shows Dennis O'Kelly's stables inside the course. The course now runs inside the site, and Downs House. Eclipse's first race may have started from near Banstead, off the map to the right.

When he arrived, he realized that the blacklegs from Munday's coffee house had got wind of Eclipse's ability, as Eclipse was the only horse in the race that anyone wanted to back. In response, his odds had contracted severely, and no layer was prepared to take bets on him at longer than 4-1 on. In other words, you would have to bet £4 to win £1; or, to put it another way again, if a horse trading at that price were to compete in five races, the betting says that he would win four times and lose only once. Eclipse had, the betting said, an 80 per cent chance of victory. Those are extraordinary odds for a debutant, and they did not interest Dennis. He had another idea for making money on the race.

Meanwhile, Eclipse's groom, John Oakley, was walking his horse to the start, four miles away in Banstead. The field were due off at 1 p.m., and Oakley was to ride. This doubling up as groom and jockey was normal. Until the early eighteenth century, owners â from Charles II, winning by âgood horsemanship', down â often rode their own horses in matches. Otherwise, they employed stable staff, who were not yet recognized as âtrainers' or âjockeys' (the latter term might mean, as it did in the context of the Jockey Club, anyone associated with the Turf).

The riding groom was a humble figure. But a groom from Oakley's era who managed to transcend the role was John Singleton, who worked for the Marquis of Rockingham. After Singleton had ridden the Marquis's Bay Malton to victory at Newmarket over a field including Herod, Rockingham commissioned for him an engraved gold cup, gave him several paintings showing him mounted on the stable's best horses, and generally treated him âmore as a humble friend than as a servant'. Singleton went on to acquire several farms and stables â a rare ascent. But it was not until the next generation, when the roles of trainer and rider split into specialities, that jockeys became noted figures, and even so they remained lower in social rank than training grooms had been. It is a class structure that persists. Jockeys such as Frankie Dettori in Britain and Garrett Gomez in the US may be jet-setting millionaires, but they are nearer in status to stable lads and lasses than they are to the leading trainers.