Eclipse (2 page)

Authors: Nicholas Clee

Dennis arrived in the capital with the qualification only of being able to write his own name. He spoke with a strong accent, which the

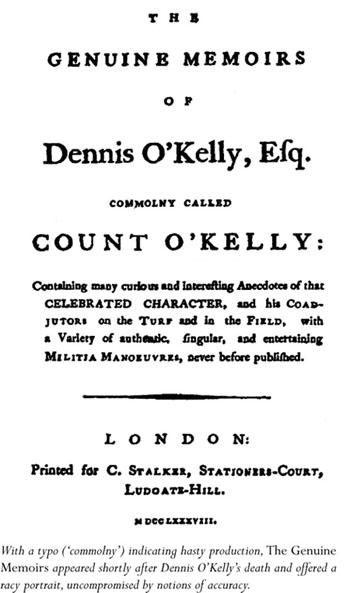

Genuine Memoirs

characterized as âthe broadest and the most offensive brogue that his nation, perhaps, ever produced', and âthe very reverse of melody'. (Various contemporary chroniclers of Dennis's exploits delighted in representing his speech,

peppering it with liberal exclamations of âby Jasus'.) He was five feet eleven inches tall, and muscular, with a rough-hewn handsomeness. He was charming, confident and quick-witted. He believed that he could rise high, and mix with anyone; and, for the enterprising and lucky few, eighteenth-century society accommodated such aspirations. âMen are every day starting up from obscurity to wealth, ' Daniel Defoe wrote. London was a place where, in the opinion of Dr Johnson's biographer James Boswell, âwe may be in some degree whatever character we choose'. Dennis held also a native advantage, according to the coiner of a popular saying: âThrow an Irishman into the Thames at London Bridge, naked at low-water, and he will come up at WestminsterBridge, at high water, with a laced coat and a sword.'

In the

Town & Country

version of Dennis's early years in London, he relied immediately on his wits. Dennis, the ingenious D.L. reported, took lodgings on his arrival in London at a guinea a week (a guinea was £1 1s, or £1.05 in decimal coinage), and began to look around for a rich woman to marry. Needing to support himself until the provider of his financial requirements came along, he decided that gambling would earn him a living, and he frequented the tables at the Bedford Coffee House in Covent Garden and other smart venues. In the convivial company of fellow Irish expatriates, he played hazard â a dice game. Very soon, his new friends took all his money.

âBy Jasus, ' Dennis said to himself, âthis is t'other side of enough â and so poor Dennis must look out for a place again.' (âD.L.' had some fun with this story.) He got a position as captain's servant on a ship bound for Lisbon. Sea journeys were hazardous, but could be lucrative if they delivered their cargoes successfully. Dennis was lucky, and got back to London with sufficient funds to support a second stab at a gambling career. This time he avoided hazard, and his expatriate chums, and stuck to billiards.

Another new friend promoted his marital ambitions, suggesting that they form a partnership to court two sisters, each of

whom had a fortune of £1, 000 a year. It was the work of a week. The partners did not want their marriages to be legally binding, so they hired John Wilkinson, a clergyman who specialized in conducting illegal ceremonies at the Savoy Chapel (and who was later transported for the practice). Before the honeymoon was over, Dennis had managed to persuade his friend to entrust his new wealth to him. Then he absconded. He spent time in Scarborough, attended the races at York, and cut a figure in Bath and in other watering-places. It was some time before he returned to London, where he found, to his satisfaction, that his wife â with whom he had no legally binding contract â had become a servant, and that his former friend had emigrated to India. They could not touch him.

However, Dennis again struggled to earn his keep. The genteel façade that was necessary in the gambling profession was expensive to maintain. And he still had a lot to learn. In order to dupe âpigeons', as suckers or marks were known, he employed a more experienced accomplice, with whom he had to share the proceeds. Before long, Dennis fell into debt again.

Version two of Dennis's story, from the

Genuine Memoirs

, has come to be the more widely accepted. In this one, he made use of his physical prowess. Leaving behind several creditors in Ireland, he made his way to London and found a position as a sedan chairman. Sedan chairs, single-seater carriages conveyed by horizontal poles at the front and back, were the taxis of the day. There were public, licensed ones, carried by the likes of Dennis and his (unnamed) partner; and there were private ones, often elaborately decorated and carried by men who were the antecedents of chauffeurs. The chairs had hinged roofs, allowing the passenger to walk in from the front, and they could be brought into houses, so that the passenger need not be exposed to the elements. Dennis, who was never shy or deferential, took advantage of the access to make himself known above and below stairs:âMany and oftentimes, ' the

Genuine Memoirs

reported, âhas he carried great personages, male and female, whose secret histories have been familiar to his knowledge.'

The Covent Garden Morning Frolick

by L. P. Boitard (1747). Betty Careless, a bagnio proprietor (a bagnio was a bathing house, usually a brothel too), travels to work in a sedan chair. Hitching a ride, without a thought for the poor chairmen, is one of her lovers, Captain Montague. Dennis O'Kelly was the âfront legs' of a chair.

The physical burdens were the least of the trials of the job. Chairmen carried their fares through London streets that were irregularly paved, and pockmarked with bumps and holes. There was dust when it was dry, and deep mud when it was wet. The ingredients of the mud included ash, straw, human and animal faeces, and dead cats and dogs.The winters were so fierce that the Thames, albeit a shallower river than it is now, sometimes froze over. Pipes burst, drenching the streets with water that turned rapidly to ice. Illumination was infrequent, as the duty of lighting thoroughfares lay in part with the inhabitants, who were not conscientious; people hired âlink-boys' to light their journeys with firebrands. In daylight, too, it was often hard to see far ahead: London smogs, even before the smoky Victorian era, could reduce visibility to a few feet.There was intense, cacophonous noise: carriages on cobbles; horses' hooves; animals being driven to market; musicians busking; street traders shouting.

The chairmen slalomed through this chaos with the ruthlessness of modern bike messengers. They yelled âBy your leave, sir!', but otherwise were uncompromising: a young French visitor to London, taking his first stroll, failed to respond to the yells quickly enough and was knocked over four times. Chairmen could set a fast pace because the distances were not huge.A slightly later view of the city from Highgate (the print is in the British Library) shows the built-up area extending only a short distance east of St Paul's (by far the most imposing landmark) and no further west than Westminster Abbey.To the north, London began at a line just above Oxford Street, and ended in the south just beyond the Thames. Outside these limits were fields and villages. The chairmen carried their customers mostly within the boundaries of the West End.

Dennis was in St James's when he met his second significant patroness (after the Dublin coffee house owner). Some three

hundred chairs were in competition, but this November day offered plenty of custom: it was the birthday of George II. Horsedrawn coaches could make no progress through the gridlocked streets, and the chairmen were in demand. A lady's driver, frustrated on his journey to the palace (St James's Palace was then the principal royal residence), hailed Dennis from his stalled vehicle. Dennis leaped to the lady's assistance, accompanying her to his chair and scattering the onlookers who had jostled forward to view such a fine personage. He âacted with such powers and magnanimity, that her ladyship conceived him to be a regeneration of Hercules or Hector, and her opinion was by no means altered when she beheld the powerful elasticity of his muscular motions on the way to the Royal residence. Dennis touched her ladyship's guinea, and bowed in return for a bewitching smile which accompanied it.'

2

You may conclude that this mock-heroic description is an acknowledgement that the story is preposterous. But the eighteenth century was a period of great social, and sexual, intermingling. In some ways (ways that Dennis would learn about, but never respect), the class structure was rigid; in others, it mattered little. Important men conducted open affairs with prostitutes and other humble women, and from time to time married them. Not so many grand women took humble men as lovers, but a few did. Lady Henrietta Wentworth married her footman. Adventurous sex lives were common. âMany feminine libertines may be found amongst young women of rank, ' observed Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, the renowned letter writer. Lady Harley was said to have become pregnant by so many lovers that, the historian Roy Porter recorded, her children were known as the âHarleian miscellany'.

The day following Dennis's encounter with Lady â (the

Genuine Memoirs

gives no name or initials), he was loitering outside White's Chocolate House, musing on her smile, when an elderly woman asked him the way to Bolton Row in Piccadilly. She offered him a shilling to escort her there. When they arrived, she invited him in from the cold to take a drink. The mistress of the house greeted Dennis and asked him whether he knew of any chairmen looking for a place. âYes, Madam, ' Dennis answered, âan' that I do: I should be very glad to be after recommending myself, because I know myself, and love myself better than any one else. 'Well, then, the woman replied, he should go to the house of Lady â in Hanover Square, mention no name, but say that he had heard of the vacant position. âGod in heaven bless you, ' Dennis exclaimed, draining his substantial glass of brandy.

The next morning, Dennis dressed himself as finely as he could, and presented himself in Hanover Square. He made the right impression, got the job, at a salary of £30 a year, and started work the next day. Standing in the hall, self-conscious in his new livery and excited at this access to grandeur, he looked up to see his mistress descending the staircase. She was of course the same Lady â whose teasing smile had occupied his thoughts since their journey to the palace. But she offered no hint of recognition. She hurried into her chair, making it known that she wished to be conveyed to the Opera House. Her expression on arrival was more encouraging; and when, at the end of her appointment, she came out of the theatre, she blessed Dennis with another smile, more provocative than before. Taking his hand, she squeezed it gently round a purse. He felt his strength liquefy; a tremendous effort of concentration was required to force his trembling limbs to carry the chair safely home. Alone, he opened the purse, to find that it contained five guineas.

The next day was busy. No sooner had Dennis returned from an errand to the mantua maker (a mantua was a skirt and bodice open in the front) than he was off again to the milliner, and then to the hairdresser, and then to the perfumer. Last, there was

a parcel to deliver to Bolton Row â specifically, to the house where he had received the tip-off about his job.

Again, he was invited in, but this time ushered into a back parlour, where â as the

Genuine Memoirs

described the scene â a giant fire was roaring and where the only other illumination came from four candles. Dennis sat himself close to the blaze, the delicious heat dispersing the cold in his bones. A young woman, with shyly averted face, brought him a tankard of mulled wine. He drained half of it in a gulp. More warmth suffused him; he did not want to move from this room. He looked at the girl, who for some reason was loitering by the door, and got a general impression of comeliness. He asked her what she was called. She replied obliquely: she had been asked to entertain Mr Kelly

3

until her mistress should return, âand indeed I am happy to be in your company, Sir, for I do not like to be alone'.

This was promising, Dennis thought. âUpon my soul, ' he asserted, âI am equally happy, and wish to be more so. Come sit by me.'

The girl approached, sat, and turned towards him. She was Lady â. They fell on each other; bodices, and other garments too, were ripped. As evening turned to night, and as the fire subsided, they enjoyed mutual happiness. At last, Lady â said she must leave. Exchanging her servant's clothes for her usual ones, and leaving Dennis with another purse, she sought her coach, which had been waiting a few doors away.

Dennis, more dazedly, reassembled his attire. Returning to the workaday world was a wearying prospect. But there was another surprise, less welcome, in store. The door of the parlour opened, and the old woman whom he had conducted to the house three days earlier entered. You have done well for yourself, she observed; such fortune would never have befallen you had it not

been for my assistance. No doubt you would want to reward me accordingly â my mistress and I depend on taking advantage of such eventualities. Your mistress gave you a purse earlier, and, as a man of honour, you should share it.