Eclipse (5 page)

Authors: Nicholas Clee

Charles James Fox, the brilliant Whig politician, whose girth and features at the age of thirty-three were evidence of his self-indulgence. A reckless gambler and womanizer, he ended up happily married to Elizabeth Armistead, a former ânun' at the establishment of Charlotte Hayes's forerunner, Mrs Goadby.

This anecdote comes from Theodore Cook's

Eclipse and O'Kelly

, published in 1907, and the standard work on the great horse and his owner. Cook observed, âPhilosophic foreigners might well have imagined that England was little better than a vast casino from one end of the country to the other.' The Duke of Queensberry (âOld Q'), a notorious rake, once bet someone that he could convey a letter fifty miles in an hour. He won by inserting the letter into a cricket ball and hiring twenty-four men to throw it to one another around a measured circle.

Horsemen not only raced, they also contrived more exotic equestrian activities on which they and their circle could bet. On 29 April 1745, Mr Cooper Thornhill rode from Stilton in Cambridgeshire to London, from London back to Stilton, and from Stilton back to London again, covering the two hundred-plus miles in eleven hours, thirty-three minutes and fifty-two seconds. âThis match was made for a considerable sum of money, ' reported William Pick in his

Authentic Historical Racing Calendar

(1785), âand many hundred pounds, if not thousands, were depending on it.' More fancifully, Sir Charles Turner made a âleaping match' with the Earl of March for 1, 000 guineas: Sir Charles staked that he would ride ten miles within an hour, and that during the ride he would take forty leaps, each of more than a yard in height. He accomplished the feat âwith great ease'. At Newmarket in June 1759, Mr Jenison Shafto backed himself to ride fifty miles in under two hours, and came home in one hour, forty-nine minutes and seventeen seconds. âTo the great admiration of the Nobility and Gentry assembled, he went through the whole without the least fatigue, ' Pick noted. For an even more gruelling challenge, Shafto commissioned a Mr Woodcock to do the riding on his

behalf. He made a match with Mr Meynell for 2, 000 guineas that Woodcock would ride a hundred miles a day for twenty-nine consecutive days, using no more than one horse a day. Woodcock started early each morning, his route illuminated by lamps fixed on posts. His only crisis came on the day when his horse, Quidnunc, broke down after sixty miles; he had to requisition a replacement and start again, and he did not cover the 160-mile total until eleven o'clock that night. But he went on to complete his schedule.

Gambling was not only a sport for grandees. The middle classes and the lower orders loved it too. Horse race meetings, cricket matches, boxing matches and cock fights all offered wagering opportunities, both at the main events and at various side shows â stalls and tables with dice, cards and roulette wheels. There was a national lottery, raising money for such causes as building bridges across the Thames, with a draw staged as a dramatic spectacle at Guildhall. You could â as you cannot today â place side bets on what numbers would appear, paying touts who were called âMorocco Men' after the leather wallets they carried.

There were many gaming houses in London. Like brothels, they operated openly, but suffered occasional crackdowns. The

Gentleman's Magazine

reported one such incident: âJustice Fielding [London magistrate, and half brother of novelist Henry], having received information of a rendezvous of gamesters in the Strand, procured a strong party of guards who seized forty five at the tables, which they broke to pieces, and carried the gamesters before the justice, who committed thirty nine of them to the gatehouse [overnight prison] and admitted the other three to bail. There were three tables broken to pieces ⦠under each of them were observed two iron rollers and two private springs which those who were in the secret could touch and stop the turning whenever they had any youngsters to deal with and so cheated them of their money.'

These venues were both dodgy and the haunts of people of

all classes. They were therefore ideal settings for Dennis O'Kelly, who was by now a master âblackleg'. The origin of this term is obscure, although it may have come from the black boots that were the standard footwear of professional gamblers; or possibly the derivation was the black legs of the rook, a word that also meant sharpster. Another term was âGreek', first used to indicate a wily character by Shakespeare. Whatever the derivation, Dennis personified the meaning: a person practised in the art of cheating others out of their money. His assiduous apprenticeship âhad reduced to a system of certainty with him, what was neither more or less than a matter of chance with his competitors'.

11

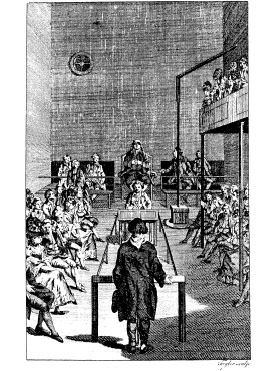

Sir John Fielding, the âBlind Beak of Bow Street', presiding at Bow Street Magistrates' Court. Dennis O'Kelly came before Sir John following a fight at the Bedford Arms; and escaped with a fine, thanks only to the intercession of a friend.

Opportunities for making a profit were everywhere â even on his feet. Dennis, on achieving a level of affluence, wore gold buckles on his shoes, while also owning a pair of buckles made of pinchbeck, an alloy that resembles gold. If he wore the gold ones, he kept the pinchbeck buckles in his pocket, and vice versa. In company, one of his companions would strike up a discussion about whether the Count's buckles were gold, and encourage the pigeon (dupe) to bet on the question. Dennis would simply perform a bit of sleight of hand, no doubt during some distracting activity initiated by the companion, to produce the buckle that would take the bettor's money.

He continued to get into trouble. At the Bedford Arms, he won money from an American officer who, probably with good reason, suspected that chicanery had taken place, and refused to pay. There were scuffles, and eventually Dennis came before Sir John Fielding.

12

Sir John was inclined to be harsh, but Dennis was rescued by the actor, playwright and fellow Fleet graduate Sam

Foote, who persuaded the magistrate to accept a fine. Dennis's relief, according to

Nocturnal Revels

, was overwhelmed by his sense of ill treatment.

âBy Jasus, ' he exclaimed, licking his wounds at Tom's CoffeeHouse, âhe [the American officer] has ruined my character, and I will commence an action against him.'

âPoh, poh, ' said Foote, âbe quiet. If he has ruined your character, so much the better; for it was a damn'd bad one, and the sooner it was destroyed, the more to your advantage.'

Mortifyingly, this riposte earned hearty laughter from Tom's clientele. Dennis had to prove that he was a sport by laughing too, especially as he was in Foote's debt.

At least he had the good spirits to rise to this challenge. His cohorts at the gambling centres of London included Dick England, in whom good spirits were entirely absent. England was a version of Dennis with the charm removed, and brutality added. Like Dennis, he was an Irish expatriate. Emerging from an âobscure, vulgar and riotous' quarter of Dublin, he took an apprenticeship to a carpenter; but the only manual activity for which he showed an aptitude was fighting. Like Dennis, he became the protégé of a businesswoman â his was a bawd. England was rumoured to be involved in highway robbery, and when one of his companions was found shot at the scene of a crime he decided that it was time to decamp to London, setting himself up at a house of ill repute called the Golden Cross. He soon rose in the world, to an address in Piccadilly, where he acquired a manservant, a pair of horses and a smattering of French. There was an awkward moment when his former mistress, who âcould not boast of a single attribute of body or mind to attract any man who had the use of his eyes and ears',

13

turned up on his doorstep, but he got rid of her with a hefty pay-off. Back in Dublin, she used the money to drink herself to death.

Contemporary magazines offer various dismal accounts of the outcomes of England's tricks. At the rackets courts, he cultivated the Hon. Mr Damer, a decent player, before going off to Paris in search of a better one, hiring him to play regularly against Damer, and instructing him to start off by losing. He pretended to back Damer; and Damer, encouraged by the support and by belief in his superiority, backed himself as well â thereby losing up to 500 guineas at a time. With debts of (according to

The Sporting Magazine

) 40, 000 guineas, Damer threw himself upon the mercy of his father, but despaired of getting help. Even while his father's steward was on the way to town with the money, Damer was in Stacie's hotel, sending out for five prostitutes and a fiddler called Blind Burnett. He watched them cavort for a while, put a gun to his temple, and fired.

England's most notorious swindle, recounted in Seymour Harcourt's

The Gaming Calendar

(1820), was one of his rare failures. While passing some time in Scarborough, he got into company with Mr Daân (hereafter called Dawson),

14

a man of property. At dinner, England refilled Dawson's glass assiduously, softening him up for the card game to follow, but he overdid it, causing Dawson to complain that he was too drunk to play. Sure enough, once the cards came out, he descended into a stupor. The conspirators, though, soon devised a fall-back plan to part him from his money. Two of them wrote notes, one recording âDawson owes me 80 guineas', the other âDawson owes me 100 guineas'; England wrote a note saying, âI owe Dawson 30 guineas'. The next day, he met Dawson, apologized for his drunkenness and rough behaviour of the previous evening, said he hoped he had given no offence, and handed over thirty guineas.

âBut we didn't play, ' Dawson pointed out.

âGet away wit' ye, ' England assured him. âAn' these be your fair winnings an' all.'

What an honest gentleman, Dawson reflected as the pair parted âwith gushing civilities'. Soon after, he bumped into England's companions. Further comparisons of sore heads ensued, and Dawson commented on the civility of their friend Mr England, who had honoured a bet that would otherwise have been forgotten.

âAs you mention this bet, sir, ' one of the companions said, âand very properly observe that it is gentlemanly to honour debts incurred when intoxicated, I hope we may be forgiven for reminding you of your debts to us'; and the fictitious notes were flourished.

âThis cannot be so, ' Dawson protested. âI have no recollection of these transactions.'

âSir, ' came the reply, âyou question our honour; and did not Mr England lately pay you for bets made at the same table?'

Defeated, Dawson promised to pay up the next day.

His own friends came to the rescue. With the help of a fiveguinea gift, they encouraged the waiter at the inn to recall that Dawson had been paralysed by drink, and had not played cards. Dawson, with some contempt, returned England the thirty guineas, adding five guineas as his portion of the supper bill. England and his cronies left Scarborough the next day.

Dennis O'Kelly may have spent some time in Scarborough,

15

but there is no suggestion that he was involved in this attempted theft. He was, though, implicated with England â and fellow blacklegs Jack Tetherington, Bob Walker and Tom Hall â in the ruination of one Clutterbuck, a clerk at the Bank of England. Clutterbuck, as a result of playing with this crowd, fell heavily into debt, attempted to defraud the bank of the sum he needed, was caught, and hanged.

Although the divisions between the classes in the Georgian era were as wide as they always have been, gambling threw together lords and commoners, politicians and tradesmen, the respectable and the disreputable. Some years later, eminent witnesses would testify on Dick England's behalf at his trial for murder. At the rackets courts, England's companion Mr Damer âwould not have walked round Ranelagh [the pleasure gardens in Chelsea] with him, or had him at his table, for a thousand pounds'.

16

One writer referred to âTurf acquaintanceship', and offered the anecdote of the distinguished gentleman who failed to recognize someone greeting him in the street.

âSir, you have the advantage of me, ' the gentleman said. The other man asked, âDon't you remember we used to meet at certain parties at Bath many years ago?'

âWell, sir, ' the gentleman told him, âyou may speak to me should you ever again meet me at certain parties at Bath, but nowhere else.'

17

The fortunes of Charlotte Hayes, too, began to look up on her departure from the Fleet. Her newly won freedom from debtors' prison received ironic celebration in Edward Thompson's 1761 edition of

The Meretriciad

, as she took advantage of the new King's clemency to begin her ascent to the pinnacle of her profession:

See Charlotte Hayes, as modest as a saint,

And fair as 10 years past, with little paint;

Blest in a taste which few below enjoy,

Preferr'd a prison to a world of joy:

With borrow'd charms, she culls th'unwary spark,