Emperor of Japan: Meiji and His World, 1852’1912 (74 page)

Read Emperor of Japan: Meiji and His World, 1852’1912 Online

Authors: Donald Keene

Tags: #History/Asia/General

The deterioration of morals could not be attributed solely to the failure of the new education introduced since the Restoration. But even if the effects of education were not immediate, it was the best cure for the prevailing situation. If the government took the lead in promoting education and remedying the inadequacies of the present system, it was reasonable to hope that Japan would achieve a “civilized” state. It

ō

expressed opposition to any attempt to create a national religion that would combine old and new in consultation with the classics, as this would require the appearance of a sage, and in any case, it was not for the government to control.

It

ō

favored technical education as the way to wean young samurai from the Confucian partiality for empty political arguments which in turn had led to their susceptibility to radical ideas from the West. Practical learning, rather than political discussions, should be the core of education. He concluded by recommending that only outstanding students be allowed to study law and politics.

20

The emperor showed It

ō

’s memorial to Motoda, who recognized it was a serious attempt to amplify the emperor’s views on education and to make up for oversights. However, he continued, the views expressed in the memorial suggested that It

ō

did not perfectly understand the emperor’s wishes. Motoda asked to be authorized to prepare a reply, and when he did, it was to reject It

ō

’s views completely. He insisted that the Four Books and Five Classics of Confucianism must be the core of education, followed by works of national learning that treated ethics and, only at the end, Western books. It

ō

had said that one should not expect immediate results from education, but Motoda asked what would happen in the future if the foundations were not laid today. It

ō

had urged that no national religion be established, at least at this time, but Motoda demanded when a more appropriate time would be. Even European countries had national religions. Since ancient times, Japan’s advances had been achieved by revering the heavenly ancestors and adopting Confucianism. “The national religion of today is none other than a return to the past.”

21

Motoda was pleased, however, that a minister of education had been appointed. The position, long vacant, had recently been assigned to the councillor Terashima Munenori in addition to his regular duties. He hoped that the emperor would communicate to Terashima his wishes on education. The emperor sent for Terashima the next day and gave him Motoda’s two essays, It

ō

’s memorial, and the draft bill on education passed by the Genr

ō

-in.

22

The new educational bill was in forty-seven articles. It prescribed opening schools at every level from elementary to university. Government elementary schools were to be established in every village and town except where satisfactory private schools already existed. In those places that lacked the means to establish schools, touring professors would be provided. A child’s education would last for eight years, from the sixth to the fourteenth year. Parents or guardians would be responsible for sending the children to school. Although loopholes in the act permitted parents to get around this obligation, it came close to mandating compulsory education for all Japanese children, a sign of the importance attached to education by the government, despite its chronic lack of funds.

The educational system that emerged from the revisions to the 1872 school system was not a success. The new system that had been laboriously constructed during the past seven years was thrown into confusion, and there was a marked decline in educational standards. The liberalization intended to free education of the straitjacket of bureaucratic administration resulted in a laissez-faire policy that did not appeal to members of the government or the emperor. Accordingly, Tanaka Fujimaro was replaced as minister of education, and his successor, K

ō

no Togama, who had accompanied the emperor on visits to schools in the countryside, was dismayed by what he observed. He therefore decided to reform the education law by strengthening the central and regional officers’ authority.

23

In December 1880 the Genr

ō

-in approved a modified educational law providing that morals (

sh

ū

shin

) would rank at the top of all subjects taught.

24

From about this time, Meiji seemed to assume a noticeably more conservative outlook. Motoda’s influence is apparent in the emperor’s insistence on Confucian values in education. Of course, each generation tends to contrast the feckless youth of its own time with the uncomplicated but sincere young people of the past. But the shift in educational policy suggests that even though the government was dedicated to progress and the propagation of practical learning, it was not content merely with lamenting the loss of old-fashioned morality but was ready to compel the young to submit to tradition. As Asukai Masamichi wrote, “The route to the Rescript on Education of 1890 had been opened.”

25

Portrait of Emperor Meiji. This photograph, the earliest taken of Meiji, shows him in traditional robes and headgear.

Courtesy the Yokohama Archives of History

Portrait of Emperor K

ō

mei. This official portrait reveals nothing of K

ō

mei’s personality.

Courtesy the Collection of Senny

ū

-ji

Portrait of Emperor K

ō

mei. The intense expression on K

ō

mei’s face contrasts with his placid appearance in the earlier portrait.

Portrait of Empress Haruko, posthumously known as Sh

ō

ken. Unlike the emperor, the empress did not object to having her photograph taken.

Courtesy Charles Schwartz, Ltd.

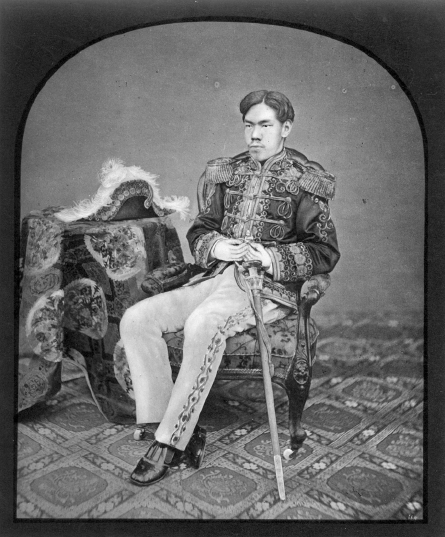

Official portrait of Emperor Meiji. This photograph was taken specifically in order to exchange it with photographs of foreign monarchs sent to the emperor. Meiji’s hair has been cut, and the beginnings of a mustache and beard are evident. Meiji continued to wear this old-fashioned uniform long after it had disappeared from Europe.

Courtesy Charles Schwartz, Ltd.

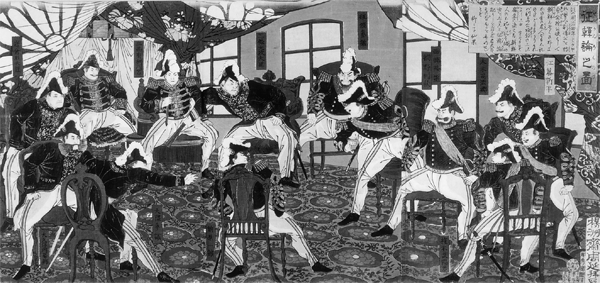

The advisability of an invasion of Korea (

seikan

) being disputed by members of the cabinet. Print by Hashimoto Chikanobu (1877). The figure to the upper left is probably Meiji. Others portrayed in this print include Saig

ō

Takamori, Iwakura Tomomi, Sanj

ō

Sanetomi, Itagaki Taisuke, Et

ō

Shimpei, and

Ō

kubo Toshimitsu.

Courtesy the Kanagawa Museum

Portrait of Saig

ō

Takamori. Print by Suzuki Toshimoto (1877). Saig

ō

’s mustache and beard, not found in most portraits of him, probably represent the artist’s guesswork.

Courtesy the Kanagawa Museum