Equilateral (10 page)

Authors: Ken Kalfus

He says quickly, to the astronomer, “We’ve already conceded that we won’t be done by June the seventeenth. The Flare will be delayed. Most of the Equilateral may be excavated this summer, but I can assure you, Sanford, that for there to be any possibility of completing it at all, by any date, then stoppages and sabotage must be put down.”

Thayer objects: “We haven’t conceded June the seventeenth.” Ballard waves at his declaration. “For all intents and purposes—”

“It’s six weeks away!”

Ballard welcomes the opportunity to speak bluntly. “None of the sides are more than three-quarters excavated, Thayer, and less than half the area has been surfaced. You’ve been out to the sites. You’re aware of the obstacles. As for Side AB—you can see from here that we’ve made progress on the line segment radiating from the Vertex, but the excavations around mile one hundred haven’t begun yet. Taking this into account, I’d say that the entire undertaking is hardly more than fifty percent complete.”

“Fifty percent!” Thayer cries. Miss Keaton flinches, suddenly aware of the argument.

Thayer has known there were delays, but he never believed the Equilateral was this far behind schedule. “How can it be?

What have the men been doing for the last two years? We won’t be done for maximum elongation.”

“As I’ve said, Sanford.”

Thayer tries to collect himself. He turns his back from the scaffold, past Miss Keaton, deliberately not looking at her. He recalculates the problem: the current progress of the excavations, the number of men required, the amount of material needed.

“So …” the astronomer begins, speaking into the vacant air. “We have to increase pitch output. Let’s have new manufactories built at the side midpoints. We’ll assign fresh crews to Side AB, at miles one hundred, one-twenty, and one-sixty; men should be dispatched from Point B as well.”

Ballard replies, “If only we had them. If only they’d work like honest English navvies.”

Thayer nods and gazes again into the plain as the new men arrive at Point A from unmarked points, aspiring to apply their muscle to the soft, liquid sands. But no, it’s a desert mirage. The Equilateral’s being snatched from his grasp by thuggery, by illiteracy, by superstition, and by indolence.

He levels a hard stare at Miss Keaton.

The secretary quickly responds: “There were problems while you were ill. I’ve tried to keep you informed.”

She has in fact been scrupulous in her accounting of the excavations. Nothing was withheld, though he was often insensible when she read him the reports.

Ballard waits a moment, to let Thayer’s anger ripen.

Then the engineer says, “The forces arrayed against us have strengthened themselves, in the ranks of the fellahin and beyond.

The mullah of Jerusalem has issued an edict against the Equilateral. It’s

haraam

. Parliament’s angry about the delays. They’ve threatened an investigation into the Concession’s finances. That’s why we’re taking desperate measures.”

“No, of course, I understand,” Thayer says, his face gone pale. “But I won’t give up June the seventeenth, not at any cost. When would we set off the Flare if not on the seventeenth, when it will mean the most and be most unambiguously observed? Do whatever is necessary.”

The canal-builders, in the course of their history, must have also contended with brutes who would have scuttled their race’s progress. The construction of the water transport system on which life on the Red Planet depends would have required fierce determination. It would not have been put off by bourgeois morality. Rebellions would have been subdued, perhaps with force. Vast wars would have roiled the globe’s surface. They would have included the mechanized butchery that has accompanied our own military strife, augmented by more advanced and more gruesome weaponry. So Mars will not judge us harshly. The planet’s history will show that conflict was ended only through the application of the universal laws of evolution and natural selection, when the superior and inferior specimens of the Martian race diverged into separate species, as is inevitable on Earth. A race of savants and a race of slaves, with breakable necks or not.

Δ

The fellahin are assembled. On this occasion no one speaks to them. The men know they’ve come for the hangings, and the

reasons for the hangings are no more mysterious than their spades, the sun, or their thirst. The condemned stand above the crowd, at the edge of the platform, not looking at the fellahin, nor paying attention to each other. Perhaps they resent sharing the stage. In the minute before the nooses are drawn tight, their swarthy faces darken further. The lights in their eyes have already gone out when the empty sacks, which once contained flour, the wholesome odor of which occupies their nostrils, are lowered.

But something is wrong with the mechanism or the way one of the nooses has been tied or placed, and though the door drops cleanly, punctuated by a dramatic concussion when it hits the underside of the platform, the man on the right dangles alive from his rope for a full minute. His companion has obediently gone slack, his toes pointing to the ground, but the second man kicks his feet with force and precise direction, as if at a stubborn mule, while he suffocates. The carpenter-executioner looks on helplessly and turns to Thayer for guidance. Thayer can only glance away, embarrassed.

The fellahin don’t object to the hangings and they’ve brought a certain holiday anticipation to the affair. The doomed man’s struggle, however, commences a low-pitched humming within the audience. The murmurs spread among the fellahin and build as the prisoner audibly chokes. Thayer recognizes the hum as kin to the protesting drone that has accompanied the excavations from the insertion of the first spade. He hasn’t identified it before. After making one last violent exertion, which twists his body as if he’s trying to slip it through a closing doorway, the man finally expires. Justice has been done, but not without recalling

the failures of equipment and personnel that have compromised the Equilateral so far.

Δ

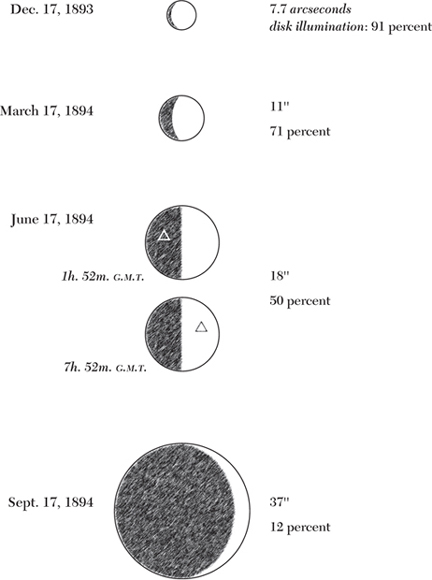

The Earth is an elusive subject for the telescopes of Mars, showing phases just as Venus, Mercury, and the moon exhibit in ours. When the full daylit face of the Earth is visible, our planet always lies on the other side of the sun, a tiny object lost in the solar glare. As the Earth catches up with Mars, increasing its apparent size, our sphere shows the Red Planet more and more of its nighttime side. At maximum elongation, June the seventeenth, the portion of the Earth facing Mars will be half lit; only for a few of the following weeks, after the minutes in which the Flare blazed from Egypt’s night shadows, will the daytime lands be sufficiently well placed to show their new equal-sided triangle. By October, when the two planets are closest, the surface of the Earth will not be visible to Mars at all.

Each civilization must wait its turn to view the other.

No one conveys the order to have the gallows removed and it remains in place after the fellahin return to work. By chance the device has been installed in the single unobstructed location where it may be seen from anywhere in Point A, from the door to the hammam, from the pitch factory, from the mosque, from the windows of the commissary, from the dormitories, and from the observatory. Thayer finds it several hundred yards before him, at the end of a long allée of tents, the moment he exits his quarters.

The astronomer listens to the camp at work. Machines are being fired up and men perform their assigned labors, but this afternoon, several days after the hangings, their reverberations reach him subdued. They’re accompanied by an undertone, the same distant strain of discontent that he recognized several days ago.

He wonders again how the inhabitants of Mars will read the Equilateral’s difficult history. With their moral development so far advanced, the severe measures taken against the laborers may remind them of their own vanishingly remote, shamefully medieval past. They may judge man too savage to conceive of friendship with him, nor imagine any sort of profitable exchange at all.

Apparent size and phases of the Earth as seen from Mars, 1894.

Δ

The sun’s forced march toward its solstice point brings longer days and greater heat, shattering records that were set in the desert the first summer of operations. The fellahin demonstrate commensurately amplified lassitude. There are more cases of sunstroke, or at least claims of sunstroke, the excavators dropping their spades and falling to the ground theatrically. Thayer receives daily accounts from the work sites. Crews employing hundreds of fellahin seem to be immobilized at mile 105 on Side AB, digging out the same sand every day.

“What’s wrong with them?” Thayer cries in frustration, dropping his fist on Ballard’s latest report. “Do they want to remain at mile one hundred five? Do they believe they’ve found Paradise there?”

“Yes, the desert is strewn with figs and virgins.” The engineer grimaces. “We offer the men instruction. We carefully translate. We account for differences in culture and national development. Still they refuse the lessons.”

Nearly every day brings news of another fatality. Today’s death occurs inside the pitch manufactory: a scaffolding gives way. Six men are trapped in the debris. Besides the fatality, one of the men loses a foot, another an eye, and two claim internal injuries of an unspecified nature. Thayer wonders why there is still scaffolding within the building, which began operation nine months ago. He wonders too how a man can so easily lose a foot; specifically what did the man fall against or into that caused his foot to be severed? In the last two years the Arabs have proven to be as prone to injuries as a circle of elderly society matrons.

Thayer rides to the factory, a three-story brick structure close to the actual Vertex of Sides AB and AC, a confluence of uniformly paved pitch nearly as large as the Point A encampment itself. Inside the building the collapse has left an amount of debris that seems far greater than the mass of the scaffolding and whatever it supported could be. Workers pick through the rubble, choose items, examine them casually, and then return them to the piles. The foreman says it will be a week before the factory is again operational.

The astronomer says, “Make it three days and that’ll be twenty pounds for you, placed directly in your account.”

The foreman doesn’t respond to the challenge.

Thayer climbs a still-intact staircase to the fourth floor, where there’s an open porch. He steps out and sharply draws in his breath. For the first time from that elevation, he views the Equilateral’s pitch-filled lines glistening wetly as they diverge from the Point A Vertex. They vanish toward points exactly sixty degrees apart on the level horizon. The foreman stands beside him, unseeing and indifferent, but Thayer is suddenly electrified, forgetting the haphazard labors going on beneath his feet. Here is the Equilateral made tangible. The pitch’s blackness is stark against the luminosity of sand and sky, the Vertex pavement like a vast hole about to swallow the Earth itself.

When Thayer finally descends, he’s inspired to return to his quarters on foot. He turns his back on the factory shambles and enters the ever-changing city invigorated. Flat stones have been laid down some of the pathways, forming rough streets and boulevards. Despite the standstill in the excavations, Point A seems to have increased in size and in the complexity of its layout, with new neighborhoods tucked into or adjacent to the original industrial sections, proliferating ad hoc alleys and plazas where they were not foreseen. Hovels and low gray tents sprawl into the distance, across the sands. There are men he doesn’t know, Englishmen and Europeans, who are startled to encounter him on the paths, and who bow once they recover themselves. The distinctive music of the closing century resonates throughout the encampment: the steam engine’s roar and the clash of heavy machine parts. A visitor can very well imagine

that the Concession was established for no other purpose than the founding of Point A as a desert metropolis. Minutes after taking his pleasure in the Vertex, Thayer is stirred by the sight of the settlement that has been engendered by his vision, his advocacy, and his unceasing labors.

Yet he’s aware that there’s been further violence. This includes blatant acts of insurrection leveled directly at the Equilateral; as well as strife traveling circuitously from abstruse causes toward obscure ends. Men are slain with pickaxes, with spades, and with knives in close fighting. Perhaps the sun, now penetrating Thayer’s helmet, has something to do with it. Meanwhile, quinine is in short supply at the infirmary and several more water tankers have gone missing. Bedouins are said to be responsible, or looters from the Sudan. Ballard has raised the prospect of water rationing, though consumption among the fellahin is already closely guarded.

In response to the growing disorder, the chief engineer has designated a mud-brick building on Point A’s outskirts as a lockup, according to terms set by the Concession with the Egyptian government. Thayer believes that it’s in another part of the city, but his uncertain footsteps lead him there anyway and, despite his growing fatigue in the heat, he stops to look in. Just inside the doorway, on a straight-backed chair absent a desk, he finds an Egyptian policeman, a Concession employee, smoking a long red-clay chibouk. Upon the astronomer’s entrance, the man abruptly stands at attention, the burning pipe still in his hands. His tunic is unbuttoned. Thayer announces that he wants to view the prisoners. For a moment the policeman remains confused and then, alarmed, he leads him to the back of the jail.