Equilateral (8 page)

Authors: Ken Kalfus

The logic of the excavations is drawn from confirmed theory.

Like Darwin’s species, the planets gain new attributes and lose others depending on conditions in their environment. Astronomers will catalogue these characteristics sometime in the next century, but one lesson that has already been learned, from observation through this century’s best instruments, is that it’s in the nature of planets to lose their water as they age. The Earth and its closest neighbors provide striking illustrations of the principle. The youngest of the three, oceanic Venus, is shrouded by clouds and most likely lacks a single island of dry land from one pole to the other. As may be seen through even a small telescope, Mars between the ice caps is almost totally waterless, on the verge of extinction. Our home planet Earth, older than the second sphere from the sun but more youthful than the fourth, is delicately poised in what Thayer calls the

terraqueous stage, its surface contested by vast seas and immense continents.

If life typically rises from a planet’s aquatic depths, then Venus most likely hosts primitive organisms similar to the algae and plankton that dominated Cambrian Earth. Mars is then home to the most evolutionally developed fauna, capable of adapting to its harsh, arid climate.

These considerations imply that the driest of the three planets, Mars, should boast the oldest, most storied, most advanced civilization. As the construction of its planet-girdling canals demonstrates, Mars has progressed far beyond mankind in the sciences and in technology. If men have operated steam engines for two hundred years, the engineers of Mars have employed them for two hundred thousand, continuously making refinements. They may have raised towers that reach the edges of the planet’s attenuated atmosphere; they may have perfected airships and other vehicles, railed or not, that can cross the ruddy globe in hours. As we can observe, they’ve developed agricultural techniques that produce bountiful crops in lands far more desiccated than the Western Desert.

We may observe that morals are another trait subject to the forces of evolution. Human history shows that ethical practices ensuring a race’s survival and well-being are naturally promoted, while malign behaviors are inexorably discarded. In the course of Earth’s past two thousand years the principles of right and wrong have been bred into the Anglo-Saxon races, which have come to dominate the planet. In their native lands contracts are honored in letter and spirit. Girls grow into ladies

with innate modesty, blessed by the sanctity of marriage. The Golden Rule has triumphed on both sides of the Atlantic. So has industry, sobriety, and self-possession.

Mars is home to a race in which the forces of natural selection have enjoyed further millennia to secure positive social traits. To judge from the planetary cooperation that must have been required to build the canal network, selflessness is imbued deeply within the Martian character. We may imagine then that Martian ethics, the product of many centuries’ further wisdom, reflection, and natural selection, have far exceeded our own—though those scruples can’t be identified in advance by the most refined, kindest man on Earth, trapped in his own species’ intermediate stage of moral development.

Thayer asserts that when we behold Mars, we’re witnessing the manifestation of Darwin’s theories on the grandest planetary scale. In demonstrating that Earth’s terraqueous state is but a phase of planetary evolution, Mars permits us a vision of our own future, existential and moral. Our planet too is destined to lose its oceans and great lakes. Earth’s orbit runs closer to the sun, so our sphere will become even hotter and drier than Mars. The deserts will spread like an infection, until water becomes as precious for us as it is for our neighbors. What will civilized man do in that event? Following the Arab’s example, he may fall into dissolution, unable to survive the climactic transformation. He may turn barbarous, atavistic, and idle. He may forget the sciences and arts that he invented, just as the Arab lost his mastery of mathematics and astronomy.

Or he may choose not to. After proving his capabilities in excavating the Equilateral, man will be ready to learn from

Mars how to assemble the social, spiritual, and material resources necessary to survive a dehydrating planet. Mars may well be the force that makes us truly civilized, truly kind to each other, wise, prudent, responsible to the natural world, courageous in facing our global challenges, and, paradoxically, truly human. Contact and communication with Mars must be the next step in human evolution. This is what Thayer believes and what he has told his audiences.

The heat demands that they travel after the sun goes down. Two lines of camels transport the swaying, muttering fellahin. He rides among them, dozing in his Bedouin saddle. Every so often the beast’s missteps jolt him awake, and Thayer is momentarily surprised to find himself there, the animal beneath him skeletal, sinewy, and hideous. The dead country is hideous too. No token of intelligence lies within his sight …

… Until he lifts his head. The Milky Way spills across the sky in a riot of light, its component stars rampaging from Sagittarius to Cassiopeia. Thayer wishes that he was already returned to Point A, where he can open the observatory. The plodding steps of his dromedary reminds the astronomer that on his own planet man lives as solitary as an anchorite on a wave-battered rock. His only companions are the animals over which he holds dominion: he can ride them, he can harness them, he can pet them, he can expect loyalty from some, and he can eat and skin them. But he can’t converse with them, not profitably.

Yet each of these stars may illuminate a world on which dwell creatures no less conscious than man; they may enjoy an intelligence and an appreciation of existence more advanced

than our own, perhaps far more advanced. Their worlds may have been in contact since men lived in caves. The sky may be congested with intellects and as lively and swarming and raucous as the Soho Bazaar on the Saturday before Christmas. We can’t hear their voices, but at this very moment sophisticated minds call to each other across the tangled, overgrown sky: instructing, inspiring, debating, and sharing their joys and sorrows.

The dragoman murmurs, “I believe it has been written so. The Forty-second sura.”

Thayer was unaware that he was speaking. He thought the translator riding alongside him was asleep. The man’s a young Cairene, with a jet-black beard and a neatly pressed galabiya, yet his eyelids are heavy and creased, heightening the typical impression of shiftiness. As dragomen go, he’s been competent enough, though Thayer can’t trust him to render fully what he’s said to the fellahin or what the fellahin have replied.

“The Prophet,” the dragoman says, taking note of Thayer’s confusion. “The verse in the Quran: ‘And one of His signs is the creation of the heavens and the Earth and what He has spread forth in both of them of living beings.’”

“I doubt that applies,” Thayer snaps. “Mohammed was an illiterate trader nine hundred years before Copernicus. He couldn’t have been aware of life on other planets.”

When the dragoman bows, his head vanishes behind the hood of his cloak. “I’m certain you’re correct, Effendi. What I know of the Quran and what the Quran may yet reveal are to each other only as a fragment of a grain of sand compares to a desert far greater than the one we traverse tonight.”

They ride for a while and Thayer, irritated, observes that the

dragoman’s asleep again, if he was ever awake. In the moment before the Arab interrupted his thoughts, Thayer almost heard the celestial intercourse above his head—if not the actual words, then its beat and hum, its susurrations and sibilations.

On his own planet the man of intelligence is the loneliest creature of all. Thayer rides in a caravan of the illiterate and the ignorant, the faithless and the fanatical, for whom the waking state and the unconscious hold no important distinction, across a wasteland in which nine hundred thousand similarly shallow souls, dispersed in their rugs and buried in their trenches, drowse while their mouths work soundlessly in their slumbers, their muscles twitch, and their dreams remain incoherent.

He raises his head again and his eyes fill with starlight.

A pit about forty feet deep has been opened in the trench on Side AC at mile 191, near Sitra. A pyramid assembled from blocks of stone stands partially uncovered within the hole, its apex only a few feet above the plane of the side’s excavations.

Thayer walks with care along the circumference, the Greek foreman at his side. The pyramid’s unweathered, neatly fitted stones are coolly luminous, nearly transparent. One of the cubes near the top has been removed, leaving a black space through which snakes a rope ladder.

The foreman says, “This is an important discovery, sir. No one has found anything like it so far west of the Nile. Other pyramids may be buried nearby.”

The monument is an ideal form made real, hewn from the rough, amorphous, uncooperative, imperfect, inexact Earth. Thayer nods at the ladder.

“Your men have gone in?”

“Only to investigate. Nothing was disturbed.”

“Did they reach the base? How deep is it?”

The foreman candidly grins. “They tied six ladders together

before they reached the bottom. Then we removed the ladders and measured the total length. I swear, we could not believe it. The pyramid’s depth is four hundred feet!”

Thayer takes another walk around the structure. Each of the exposed faces appears to be equilateral.

The foreman whispers, “We found treasures, sir: golden bulls, rams of porphyry, papyrus scrolls on which are written the histories of unknown dynasties …”

Thayer does the calculations in his head, estimating that the surface area of the four triangular sides and the square base is about eight hundred thousand square feet. Let’s say each block is four feet deep: then beneath his boots are more than three million cubic feet of stone, transported to this stoneless plain four thousand years ago. The stones, like those of the famous pyramids at Gizeh, would have had to be quarried in the Arabian mountains, transported down the Nile and across the desert, and then assembled to a height greater than St. Paul’s Cathedral—without the use of pulleys or the convenience of wheels, or the luxury of a lever.

“But we did remove one artifact, sir. It’s a kind of toy or device.”

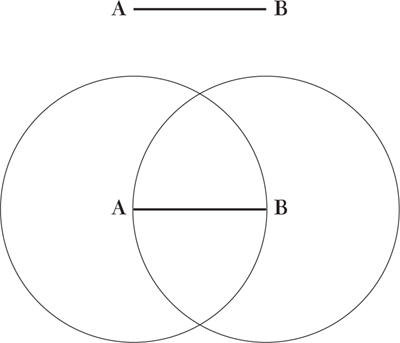

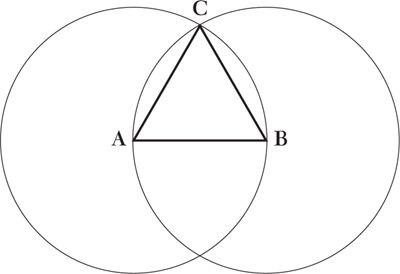

Thayer takes the machine. It’s a simple drafting compass, perfectly preserved, two flat arms of beaten metal hinged at their ends, their other extremities terminating in still-sharp points. A straightedge must have lain beside it. With a straightedge, a man may score a line segment on stone. Taking up the compass, he may then draw two circles around the segment’s end points, each circle the same diameter as the segment. The circles will intersect at two points; each of those points is the

vertex of an equilateral triangle drawn from the segment’s end points, according to the first proposition of Euclid’s first book, composed in Alexandria. The man may then go on to draw lines of equal lengths and manipulate lines and quantities that are unequal. With a straightedge and a compass he may plot further triangles right, acute, and obtuse, and then larger polygons; he may contemplate solid geometry. He may invent quadratic equations. He may survey the lands annually irrigated by the Nile. He may predict the motions of celestial objects. He may create a civilization.

Euclid’s first proposition.

The pyramid must have been seen as an impossible endeavor by the savants of its time, yet the builder had maintained confidence in its completion. He knew that his idea for the monument, whatever the enigma of its purpose, was as perfect as his geometry. If the pharaoh ran short of funds, if the slaves rebelled, if the Nile ran dry and grounded the fleet of barges that were tasked to bring the stones from their distant quarries, the geometry’s integrity would restore the project, compelling flawed men to kneel at the altar of its flawlessness.

“Thank you, but there’s no time to be lost,” Thayer says. “Please bury it again so that we can lay the pitch. We have to finish excavating the segment. My friend, Mars will not wait.”