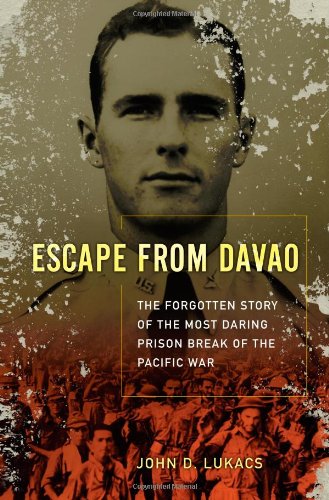

Escape From Davao

Authors: John D. Lukacs

Tags: #History, #General, #Military, #Biological & Chemical Warfare, #United States

The Forgotten Story of

the Most Daring Prison Break

of the Pacific War

ESCAPE

from

DAVAO

John D. Lukacs

Simon & Schuster

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.simonandschuster

Copyright © 2010 by John D. Lukacs

Al rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book

or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Simon & Schuster Subsidiary Rights Department,

1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020

First Simon & Schuster hardcover edition June 2010

SIMON & SCHUSTER and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases,

please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at

1-866-506-1949 or [email protected].

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event.

For more information or to book an event contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com.

Designed by Paul Dippolito

Manufactured in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Lukacs, John D.

Escape from Davao : the forgotten story of the most daring prison break of the Pacific war / John D.

Lukacs.—1st Simon & Schuster hardcover ed.

p. cm.

1. World War, 1939–1945—Prisoners and prisons, Japanese. 2. World War, 1939–1945—

Philippines—Davao City. 3. Prisoner-of-war escapes—Philippines—Davao City—History—20th century.

4. Escaped prisoners of war—United States—Biography. 5. Escaped prisoners of war—Philippines—

Davao City—Biography. 6. Davao City (Philippines)—History, Military—20th century. 7. Philippines—

History—Japanese occupation, 1942–1945.

8. World War, 1939–1945—Underground movements—Philippines. 9. Guerril as—

Philippines—History—20th century. 10. Soldiers—United States—Biography. I. Title.

D805.P6L85 2010

940.54’7252095997—dc22 2010003238

ISBN 978-0-7432-6278-1 (ebook)

ISBN 978-1-4391-8043-3 (ebook)

To the memory

of my father,

John F. Lukacs

Contents

Author’s Note

PART I • WAR

1

Ten Pesos

2

A Long War

3

The Raid

4

God Help Them

PART II • HELL

5

The Hike

6

Goodbye and Good Luck

7

A Rumor

8

The

Erie Maru

9

A Christmas Dream

10

A Big Crowd

11

The Plan

12

Cat-and-Mouse

PART III • FREEDOM

13

A Miracle

14

Another Gamble

15

Unexplored

16

Little Time to Rest

17

A Story That Should Be Told

18

Duty

19

Greater Love Hath No Man

20

Legacies

21

Conditional Victory

Acknowledgments

Notes

Bibliography

Index

I had tried to put into words some of the things that I have experienced and observed during

these past months, but I fail to find words adequate to an accurate portrayal. If any American

could sit down and conjure before his mind the most diabolical of nightmares, he might

perhaps come close to it, but none who have not gone

[

through

]

it could possibly have any

idea of the tortures and the horror that these men are going through.

—MAJ. WILLIAM EDWIN DYESS, AUGUST 16, 1943

ESCAPE

from

DAVAO

Author’s Note

A verse from a poem written by Lt. Henry G. Lee, a junior officer in the Philippine Scouts, precedes each chapter. Lee, a native of Pasadena, California, was captured by the Japanese after the fal of Bataan in April 1942 and endured the infamous Bataan Death March.

Throughout the ordeal of his captivity, Lee wrote approximately thirty poems in two canvas-wrapped notebooks. These notebooks were unearthed beneath the site of the Japanese prison camp cal ed Cabanatuan in 1945. Lee had buried his works before departing the Philippines on an unmarked prison ship that was sunk by U.S. warplanes in December 1944. Lee was kil ed when the second hel ship he was aboard, the

Enoura Maru

, was also bombed and sunk in Takao Harbor, Formosa, on January 9, 1945.

Several of Lee’s poems appeared in

The Saturday Evening Post

in November 1945 and al were later published in their entirety in a compilation entitled

Nothing but Praise

.

Throughout the book I refer to geographical locations by the name by which they were known at the time.

Thus, the island of Taiwan is cal ed Formosa, its Japanese name.

MONDAY, AUGUST 16, 1943

Washington, District of Columbia, United States

Maj. Wil iam Edwin Dyess, U.S. Army Air Forces, serial number 0-22526, was not official y here. Not in Washington. Not seated in one of the innumerable offices catacombed inside the vast reinforced-concrete bowels of the brand-new Pentagon building. For al intents and purposes Dyess’s presence in the United States was classified. Yet the dark cloak of secrecy, wartime protocol though it was, was perhaps unnecessary. After al , the mere supposition that Dyess was alive was almost unbelievable.

An exhausted apparition in loose, il -fitting khaki, Dyess did not look very much like the dashing hero the newspapers had described him to be, a decorated pilot who wore some of his nation’s highest honors—including both the Distinguished Service Cross and the Distinguished Flying Cross—among the multicolored ribbons pinned to his lean chest. Right now he looked like a man who had been through hel and back, in his case a terrifying real place with a real name—the Japanese-occupied Philippine Islands.

The tal Texan’s classical y handsome face was sunken and weathered, a bronzed mask drained of its youthful vivacity. Withered muscles and wispy, thinning locks of amber hair bore witness to months of malnutrition, grueling slave labor, and the insidious form of torture that he and his comrades cal ed “the sun treatment.”

A literal barefoot prophet, the erstwhile prisoner of war had carried with him throughout his odyssey few possessions: a Half and Half tobacco tin that was his bil fold; a creased, Mobil Oil map of the Philippines; his rusty wings and captain’s bars. The Presbyterian also wore a crucifix and a medal of Saint Christopher—the martyred soldier and patron saint of travelers who, in the mythos of the Catholic church, was the bearer of Christ and heavy burdens—with his dog tags. The holy objects had been given him by a dying pilot from his shattered squadron, the 21st Pursuit. Dyess had knelt by Lt. James May as he choked out his final words: “Ed, take these and wear them. Take them back to the United States when you go.” It was as if May had somehow known that Dyess, unlike so many others on Bataan, would one day return home. Thus far, the items had proved a fitting bequest.

These items were not al that Dyess carried. Frozen in his crystal ine, ice-blue eyes was a catalog of countless, soul-searing images, images that Dyess had purposeful y and painful y carried through his waking hours and fitful dreams, images that could never be permanently laid to rest—images that no eyes should see.

Dyess had returned to the States exactly one week earlier, on Monday, August 9, his twenty-seventh birthday. But there were no throngs of relatives and wel -wishers to welcome him, no popping flashbulbs and reporters waiting to chronicle the pilot’s first triumphant steps on American soil in nearly two years.

Instead, he arrived anonymously in Washington, the only news of his arrival a telegram he had somehow secretly conspired with Western Union to send to his wife in Champaign, Il inois, a few days before.

WILL ARRIVE CHICAGO VIA UNITED AIR LINE 2:30 PM AUG 13. REMAIN 30 MINUTES.

MY PRESENCE IN US SECRET TELL NO ONE NOT EVEN FOLKS.

According to a newspaper account published months later, Marajen Stevick Dyess received “little more than a glimpse of her young husband” that day. And only later, “from a certain room in a certain hotel at a certain time [Dyess] was able to talk to his parents in Albany [Texas] by phone.” It was perhaps the most bizarre, guarded homecoming ever afforded an American war hero.

But mystery had surrounded Dyess since the fal of the Philippines in early 1942. The last word anyone had received from him had been an Easter telegram sent from an overseas wireless station on the Philippine island of Cebu. In the succeeding months, as tales of Dyess’s battlefield bravery began to appear in publications smal and large—from his hometown

Albany News

to the

Fort Worth Star-Telegram

to

Esquire

magazine—Dyess’s legend grew. A correspondent from the

New York Times

, in an article detailing Dyess’s intrepid leadership and battlefield exploits on Bataan, referred to him as the