Escape From Davao (10 page)

Authors: John D. Lukacs

Tags: #History, #General, #Military, #Biological & Chemical Warfare, #United States

Motoo Nakayama. Nakayama, angered that King did not have the authority to surrender al of the Fil-American forces in the Philippines, was truculent and condescending. He was further insulted when, after demanding King’s sword, he learned that the general had left his saber in Manila. King convinced Nakayama to accept his pistol instead, but was unable to convince the Japanese to agree to his plan to use USFIP trucks to transport the surrendered troops to a place of Homma’s choosing. Nakayama refused to address King’s concerns about Japan’s treatment of prisoners, instead issuing only a brief, nebulous reply.

“The Imperial Japanese Army are not barbarians.”

Ed Dyess was seeing otherwise. He had been resigned to gather his squadron and surrender in an orderly fashion, but that was before he watched enemy planes strafe the unarmed troops waggling bedsheets, towels, and other makeshift surrender flags. The piercing, frightened cries of civilians and children, heard above the thunder of shel fire and bombs, rang his ears in a “symphony of despair.”

Dyess first considered joining the guerril as rumored to be operating in Luzon, but the distance was too great. He also knew that Americans could not take to the hil s without quinine to protect themselves from malaria. Peering through the smoke-fil ed haze suspended above Mariveles Bay, he saw hundreds of desperate men—some swimming, others paddling on rafts or clinging to oil drums, crates, and various pieces of debris—struggling toward Corregidor, but he could not, in good conscience, order his men into the oil-slicked, shark-infested waters.

Time, however, ran out on Dyess and his men. The Japanese army had metastasized across Bataan, closing al possible escape routes. Near Little Baguio, Dyess’s car found three enemy tanks blocking the road. Nervously, the pilots thrust their hands into the air, waving white handkerchiefs. A Japanese soldier motioned them forward, but, noticing their sidearms, quickly halted them. Frantical y unholstering their

.45s, the Americans again raised their arms. As the ranking officer, Dyess was punished for the transgression in a torrent of scalding Japanese and blows to his face. “The jig certainly was up,” wrote Dyess.

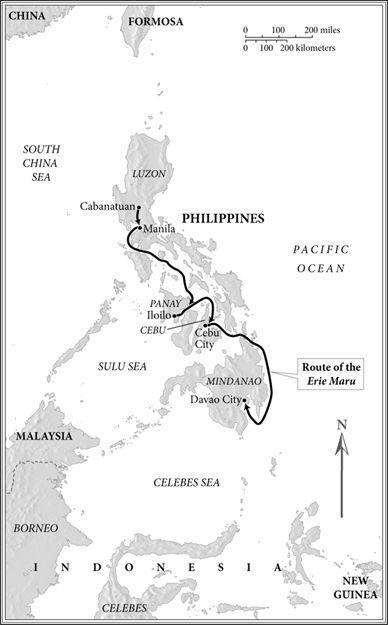

Luckily for the passengers of the Duck, now skidding across Manduriao Field with an empty gas tank, Carlos Romulo’s briefcase had not been a casualty of the airborne purge. Searchlights from Japanese ships had sparkled the sky above Cebu Harbor, forcing Romulo to produce a map of secret airfields, thus landing them here, two miles northwest of Iloilo, at dawn. They blinked in disbelief while gazing upon the flowers, green rice fields, and efflorescent splendor of an Iloilo untouched by war. And then the Victory Restaurant, a tiny shack on the field just opened for breakfast, came into focus.

While downing eight fried eggs and six cups of coffee, Romulo watched Barnick finish eleven eggs, bacon, and biscuits. Boelens ate four orders of ham-and-eggs. One passenger guzzled ten cups of fresh hot coffee. With each guilty bite, they saw the gaunt faces of friends left behind on Bataan.

Not long after the sumptuous breakfast, they gathered around a radio. Romulo recognized the voice as that of one of his assistants with the Voice of Freedom, Philippine Army 3rd Lt. Norman Reyes. Reyes’s voice quivered amid the crackling static:

Good evening everyone, everywhere. This is the Voice of Freedom broadcasting from somewhere in the Philippines. Bataan has fal en. The Philippine-American troops on this war-ravaged and bloodstained peninsula have laid down their arms. With heads bloodied but unbowed, they have yielded to the superior force and numbers of the enemy…. Al the world wil testify to the almost superhuman endurance with which they stood up until the last in the face of overwhelming odds…. Men hedging under the banner of unshakable faith are made of something more than flesh, but they are not made of impervious steel. The flesh must yield at last, endurance melts away and the end of the battle must come. Bataan has fal en, but the spirit that made it stand, a beacon to al the liberty loving peoples of the world, cannot fail.

With tears in his eyes, Romulo looked away. Though a quiet man who favored an economy of words, Leo Boelens was the only one in the group capable of a response.

“God help them.”

HELL

CHAPTER 5

The Hike

There was a blazing road that had no end

Eight thousand captives—not a single friend …

Friday, April 10, 1942

East Road, Bataan Province, Philippine Islands

The story seemed too far-fetched, too irrational—too disquieting—to be true. According to a witness recounting the story in savage detail for Ed Dyess, an American officer was being searched by a Japanese three-star private. “Al at once he stopped and sucked in his breath with a hissing sound,”

Dyess was told. The soldier had found a crumpled wad of yen, a seemingly trifling offense. But Japanese logic dictated that a prisoner in possession of currency, Rising Sun flags, or any Japanese objects must have taken the items from the body of a dead Japanese. The price for such dishonorable behavior, Dyess learned, was steep.

The Japanese officer supervising the shakedown forced the American to his knees, unsheathed his sword and raised it above his head. “There was a swish and a kind of chopping thud, like a cleaver going through beef,” said the witness. “The captain’s head seemed to jump off his shoulders. It hit the ground in front of him and went rol ing crazily from side to side between the lines of prisoners.” The headless body, spurting blood, flopped forward and the dust at the prisoners’ feet coagulated into scarlet mud. The dead man’s hands opened and closed “spasmodical y.” The executioner then hovered over the body, wiping his sword clean, before strutting off. The private, after col ecting the deceased’s possessions, continued down the line. “Now, as never before,” seethed Dyess, “I wanted to kil Japs for the pleasure of it.”

Dyess had been simmering ever since his first, foreboding encounter with the Japanese near Little Baguio, but his blood had real y begun to boil when he and the remnants of the 21st Pursuit were assembled near Mariveles the fol owing morning. The sun had burned off the dawn mist, revealing a mob scene of vehicles, refugees, surrendered American and Filipino soldiers, and swaggering Japanese troops. “A Philippines Times Square,” recal ed one American. The POWs were corral ed in sun-splashed staging areas and forced to stand at attention. Some Japanese soldiers, similarly exhausted and hungry, offered cigarettes or food from their

bento

boxes. But few were in a magnanimous mood. They had not conquered Bataan quickly or with impunity; by late April, roughly 40,000 patients suffering from everything from malaria to combat wounds would fil Japanese hospitals. And though they despised their adversaries taking so long to surrender, their ful fury was reserved for a greater affront: the fact that the Americans and Filipinos had al owed themselves to be captured at al .

According to the code of Bushido—“The Way of the Warrior”—in which al Japanese personnel had been indoctrinated, the paradoxical, paramount goal of life was death in al its glorious fealty and finality.

One who surrendered, therefore, defied his destiny of death, betrayed his emperor, his country, his family, and his comrades. In essence, he betrayed

yamato damashii

—the very soul of Japan.

In the oppressive heat, the Japanese had searched the POWs, ostensibly for weapons or items of military intel igence value, but real y for loot. They worked efficiently and forcibly, taking jewelry, Parker bal point pens, Zippo lighters, and American cigarettes. The Japanese had a fancy for wristwatches—many strutted around, their forearms decorated with a half-dozen Timexes, Hamiltons, and Elgins.

Malicious guards shredded photographs of prisoners’ loved ones. One seized a pair of eyeglasses, smashed the lenses, and walked away, leaving the prisoner to grope around. Another furiously tugged at a West Point ring on an officer’s swol en finger. Undaunted, he held the man’s hand to the trunk of a tree and, with one, swift slice from a bolo—a Philippine machete—separated both the ring and the finger from the American. Determined not to let his Randolph Field ring become a Japanese souvenir, Dyess defiantly hurled his into Manila Bay. Sam Grashio, taking his cue, tore up a photograph of his wife before the Japanese could do so. “There stil was plenty of fight left in us,” said Dyess. “We were prisoners, but we didn’t feel licked.” Their fighting days were finished but, as time would tel , they could il afford to surrender their fighting spirit.

Flanked by soldiers wearing tropic field caps with cloth sun flaps, prisoners began marching out of Mariveles, three or four abreast, in long, mosaic columns of blue, khaki, and olive drab. They moved up the steep grade of the serpentine East Road, its white, partial asphalt surface cratered and shimmering with heat waves, their eyes widened to a bewildering panorama. Guided by rays of sparkling sunlight filtering down through the jungle canopy, they passed twisted old banyan trees grotesquely splintered by shrapnel. The mangled metal hulks of fire-gutted vehicles, some licked by dying flames, littered the battle-scarred landscape. Swarming with hordes of insects, decaying bodies clogged ditches and thickets of bamboo and ipil-ipil. The impenetrable wal s of steamy emerald jungle receded, revealing a hissing, crackling funeral pyre of corpses, timber, and cogon grass. Clouds of acrid, brooding smoke, mixed with the pungent perfumes of cordite and rotting flesh, wafted across the peninsula.

But it was no sightseeing tour—the pace was maddening. Successive sets of impatient, time-conscious guards incessantly spurred the prisoners forward with unintel igible Japanese and commands of “Speedo! Speedo!” Growing progressively more frustrated, they breached the language barrier with pricks and puncture wounds from their bayonets. Prisoners were also punished for their lethargy with fists, clubs, and rifle butts, and had no choice but to absorb the blows and trudge on in silent misery.

Talking consumed energy, of which they had little. It also produced a need for water, of which they had even less, despite the artesian wel s scattered about the war-torn jungle wasteland.

Even rest breaks, which were few and far between, sapped vital energy. With a flash of their steel bayonets, the guards would occasional y prod the columns of gaunt, stubble-bearded prisoners off the East Road, usual y to make room for the never-ending convoy of Imperial Army tanks, trucks, and troops slithering through the smoldering jungle. As if by design, the Japanese chose canebrakes, fields, or vacant lots that offered little or no protection from the searing rays of the soul-scorching sun. There the men would sit, sometimes for hours, and for seemingly no good reason, enduring what they would cal the sun treatment—brutal sessions of prolonged exposure that left them mental y, physical y, and spiritual y drained.

The passing motorized processions stirred ashen clouds of powder, which settled upon the prisoners, lending a spectral appearance to the shuffling masses. Near Little Baguio, Dyess and Grashio watched in horror as the Japanese swept sick and wounded prisoners from Field Hospital No. 1 into the march.

For nearly a mile, these men—some of whom were amputees—hobbled along, their bloody field dressings unraveling with each excruciating step. Grashio saw one legless Filipino dragging himself forward with his arms. “I can never forget the hopelessness in their eyes,” Dyess would write.

While most of these hapless prisoners inevitably and perhaps merciful y fel victim to bul ets and bayonets—groups of guards cal ed “buzzard” or “clean-up” squads trailed the columns—some met more gruesome fates. One wobbly, disoriented patient, flung into an onrushing column by a cruel guard, was struck down in a grotesque crush of metal, rubber, bones, and flesh. In the subsequent procession of squealing steel treads and tires, his clothes—al that remained of the man’s existence—were embedded into the oil-slicked thoroughfare. One prisoner, Sgt. Mario “Motts” Tonel i of the 200th Coast Artil ery, a former standout footbal player at the University of Notre Dame and with pro footbal ’s Chicago Cardinals, recal ed the sound of hundreds of hooves rumbling the ground like an earthquake. A raucous troop of cavalrymen soon gal oped past, a Rising Sun flag flapping in their midst. Tonel i spied a barely discernible object bobbing above the ensign and the loud, jumbled mass of horses and humanity. Abruptly, it came into ful , horrific view: a mutilated human head, skewered atop a pike and veiled with a swarm of fat black blowflies and maggots crawling from vacant eye sockets and nostrils. “We’re in trouble,” Tonel i would say.