Escape From Davao (20 page)

Authors: John D. Lukacs

Tags: #History, #General, #Military, #Biological & Chemical Warfare, #United States

The welcome from the 1,000 Americans already present at Dapecol was cold, too. “To them,”

observed Grashio, “we seemed like poor relations.” Having arrived from the prison camp at Malaybalay in Bukidnon Province comparatively clean and wel clothed, with food, footlockers, and even a library, these POWs had experienced none of the cruelty and deprivations that the Luzon POWs had.

Eventual y, the “country club

boys” from Mindanao extended compassion to their countrymen—with curious results. One gave a tin of sardines to a skeletal newcomer only to watch him turn and sel it. They could not understand what primitive survival instincts their country cousins from Cabanatuan had resorted to.

Only a man who had been through what they had—or one who had been on Bataan—could have understood. Marooned on Mindanao, Leo Boelens had spent the past six months at Malaybalay trying to fix the problem of boredom. He played poker, wrote poetry, repaired cigarette lighters, and read voraciously, taking a particular interest in titles such as Dumas’s

The Count of Monte Cristo

. Unlike many of his complacent comrades, Boelens had begun arranging a mental schematic for movement months earlier. “[Fili] Pinos going over hil ,” he wrote in his diary on May 13. “I think over plans of going.”

But he stayed, and was reunited with Dyess and Grashio in Dapecol. While giving Dyess a shave, he learned what had transpired in his absence: “The tales they tel about the Death March from Bataan to O’Donnel ,” Boelens recal ed.

Though their current predicament seemed to be more hopeless than the last, Boelens was glad to be among friends. Abandoned by their government, a source of embarrassment for their countrymen, and unwanted by the Japanese, these bastards had no choice but to stick together.

The benefits of hewing a penal colony out of the wilds of Mindanao, as Paulino Santos saw it in the early 1930s, were many. Santos, the pioneering director of the insular government’s Bureau of Prisons, believed that not only would a prison plantation reduce overcrowding at Manila’s Bilibid Prison, it would also check the suspicious expansion of the Japanese in Mindanao.

Davao City had been occupied, economical y speaking, by the Japanese long before the arrival of the Imperial military, ever since Issei entrepreneurs had bought out coconut plantations built by American ex-servicemen—veterans of the Spanish-American War and the Philippine Insurrection—to grow abaca, the fibrous hemp plant used to make rope. By the eve of the war, the Japanese, comprising nearly 20

percent of the total population of Davao Province, control ed the hemp industry—and consequently the local economy—and were poised for a wider invasion. Success of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, after al , depended on access to the resource-rich hinterlands of Mindanao and al the gold, chrome, manganese, iron, oil, lumber, copra, and fruit contained there. So it was Santos’s prescient desire for a large, physical barrier that precipitated the creation of the Davao Penal Colony thirty miles north of “Davaokuo” in 1932. With its own hospital, railroad, and power plant, as wel as living quarters for 1,000 inmates and a staff of administrators and their families, Dapecol was essential y a self-sustaining city some 140 square miles in size.

Much of the colony’s substantial acreage consisted of fields and paddies tended by colonos, as inmates were known. But regardless of their penitential labors, few colonos entertained hope of leaving Dapecol. Since their ranks included some of the commonwealth’s most violent criminals—most were serving life sentences for murder—Dapecol was designed as an ultra-maximum-security prison along the lines of Devil’s Island, the infamous, reputedly escape-proof colonial jail in French Guiana, and Alcatraz.

Dapecol was surrounded by an impenetrable swamp that served as an intimidating deterrent to any escape plan. Stretching for nearly twenty miles in al directions, the swamp was a mosquito-infested miasma. Although tribes of headhunters reportedly frequented the area, little else but giant insects, poisonous snakes, and Philippine crocodiles lived in the swamp. The colonos and inhabitants of fringe barrios who combined Spanish Catholicism with indigenous beliefs perpetuated the myth that the bog was an evil, supernatural entity. Myth or not, despite the fact that there was no fence ringing the colony’s outer perimeter, not a single colono was believed to have escaped from Dapecol in the camp’s ten-year existence.

The war, however, brought about a unique, converse phenomenon: fleeing what was essential y a Japanese prefecture, thousands of Davaoeños seeking food and shelter broke

into

Dapecol. While the Japanese army later evicted most of the evacuees, as wel as nearly 800 inmates (who were transferred to Iwahig Penal Colony on the island of Palawan), a skeleton crew of agricultural agents and 150 colonos was left behind and tasked, according to the orders of Gen. Hideki Tojo, with teaching 2,000 American POWs how to work the colony.

Forcing POWs to labor for the benefit of an enemy’s war effort was forbidden by the Geneva Convention, but Tojo had deemed POW labor essential to the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.

A telegram relayed by the Swiss government to the United States in February 1942 stated that,

“ALTHOUGH NOT BOUND BY THE CONVENTION RELATIVE TREATMENT OF PRISONERS OF

WAR JAPAN WILL APPLY MUTATIS MUTANDIS PROVISIONS OF THAT CONVENTION TO

AMERICAN PRISONERS OF WAR IN ITS POWER.” By definition, the Latin expression

mutatis

mutandis

represents a substitution of terms; the Japanese translation was that Nippon would observe the convention only insofar as it did not clash with the existing Imperial Way. Tojo had communicated this caveat to the generals who had been assigned responsibility for POW camps during a July conference in Tokyo:

In Japan, we have our own ideology concerning prisoners of war, which should natural y make their treatment more or less different from that in Europe or America … you must place the prisoners under strict discipline and not al ow them to lie idle doing nothing but eating freely for even a single day. Their labor and technical skil should be ful y utilized … toward the prosecution of the Greater East Asiatic War.

There was perhaps no better place for an implementation of this ideology, no other corner of the empire where war prisoners could be more secretively hidden away and their labor more effectively exploited with such minimal investment in their welfare and supervision, than the Davao Penal Colony. In fact, Dapecol was so isolated that many POWs had no idea where on earth they were. Some, judging by what their officers and smuggled maps told them, knew their present location only as a point somewhere seven degrees north of the equator.

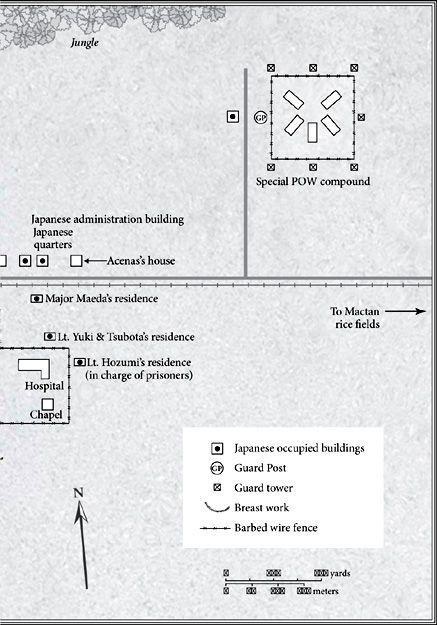

And yet, despite Dapecol’s seclusion and reputation, the Japanese were taking no chances with their American slaves. Inspecting his surroundings, Jack Hawkins found that the prisoners were being housed inside a heavily guarded rectangular stockade sited at the epicenter of Dapecol—a prison yard within a prison. Hawkins’s view, however, was limited to the 72,000-square-foot pen. If he had stood in one of the guard towers that loomed above the thirteen-foot, triple-fenced wal of barbed wire, he could have seen the entire colony in a broad, daylit panorama.

Dapecol was an open, largely treeless compound encircled by an infinite green sea of banana trees and coconut palms. A mile-long main thoroughfare stretched alongside a pair of narrow gauge railroad tracks on a west–east course that ran paral el to the prisoners’ barracks. Lining this road were a number of wooden and nipa structures, mostly warehouses cal ed bodegas, and the colony’s machine shop and diesel power plant. At the first intersection was the northern extension of Zamboanga Avenue, where the Filipino administrators’ homes were located. A row of administration buildings, as wel as guards’

quarters, straddled the main road opposite the basebal diamond, which was adjacent to the POW

compound. Giant, petrified kapok trees anchored the edge of right field while a burbling stream snaked along the left field boundary and through the prisoners’ mess area, separating the POW compound from the Japanese officers’ bil ets. Further east, Dapecol’s main thoroughfare abruptly ended, leaving only the steel rails, which fol owed a tapered furrow into the unfathomable depths of the jungle.

Conditions were spartan, but Dapecol was an improvement over Cabanatuan. Spigots and wel s provided plenty of water for drinking, bathing, and laundry. There were three large, peculiarly ornate latrines. Just outside the fence, to the right front row of the barracks facing north, was a kitchen and mess hal . There were nine barnlike barracks al otted to the POWs on the basis of rank, starting with enlisted men in Barracks One and progressing to field-grade officers in Barracks Nine. In each, between 150 to 200 men were sardined into fifteen-foot intervals of space cal ed bays. There were approximately sixteen bays per barracks, eight on each side. The Marines had laid claim to a section in the rear corner of Barracks Five cal ed Bay Ten. Hardened by the Darwinian, dog-eat-dog existence at Cabanatuan, Hawkins was caught off guard by the friendly prisoner staring at him from across the aisle.

“How ya doin?” inquired the stranger, extending his hand. “My name’s Sam Grashio.”

“Jack Hawkins,” he replied, noticing Grashio’s wings. “I see you’re a flier.”

“Yep, I was in Ed Dyess’s squadron. Twenty-first Pursuit. Do you know Dyess?”

“Yes, I just met him on the ship the other day,” replied Hawkins. “Fine fel ow, isn’t he?”

“You bet he is; finest in the world. There’s nothing the boys in the Twenty-first wouldn’t do for Ed.”

Grashio then mentioned that he was going to fil his canteen, and offered to do the same for Hawkins.

Hawkins handed his over with no hesitation—something he would not have done at Cabanatuan, a place where there was little honor even among thieves. He couldn’t quite put his finger on it, but he sensed that there was something different about Grashio.

For the circumspect, close-knit Marines, only time would tel if Grashio was someone who could be trusted with more than a canteen. And time, as any colono could tel them, seemed to stand stil at the Davao Penal Colony.

Before dawn, brassy bugle cal s blasted across the colony, commencing a tedious routine that would be replayed nearly every morning of every day throughout the next two months. After a breakfast of rice flavored with oleomargarine and starchy, carbohydrate-rich cassava roots, the prisoners were stood at attention, forced to salute the Rising Sun flag—the “flaming asshole,” it would come to be cal ed—and counted out for work details. It was an egalitarian system; almost every POW—even the sick and near-crippled, as wel as aging officers—was mustered.

Once a detail reached its manpower requirement, it joined the others marching out into the rising daylight. Prisoners went to the bodegas, and to the garage. Others were assigned latrine duty, to chop firewood, or to repair roads and fences. Many labored in the orchards—which overflowed with lemons, limes, papaya, bananas, coconuts, star apples, and jackfruit—or the south fields ful of cassava, camotes, corn, peanuts, and sugarcane. Plowers were introduced to a herd of ornery Brahma steers while yet further south thousands of clucking chickens welcomed those assigned to the poultry farm.

Most climbed aboard rickety flatcars hitched to a smal diesel engine waiting on the narrow gauge track. With a jerk, the tiny, overburdened train—it was soon christened the “Toonervil e Trol ey,” in honor of the popular cartoon strip—rol ed away, clicking past abaca and banana groves into a dank jungle where monkeys cavorted. Twenty minutes later, the passengers disembarked at the Mactan rice fields and plunged, barefoot, into the watery squares to plant, weed, or reap the rice crop. Rice was Dapecol’s

“cash crop” and much of the colony’s labor pool and acreage—depending on the season, between 350

and 750 prisoners and as many as 600 paddies—was devoted to its cultivation. The rice detail was undoubtedly the dirtiest, most demanding, and perhaps the most dangerous. The sunken paddies were fil ed with cobras and rice snakes, but an invisible predator cal ed

Schistosoma japonicum

, a parasite that penetrated sores and cuts, would prove to be their most sinister enemy.

Just beyond Mactan, POWs hauled wet gravel in five-gal on cans from a creek bed onto flatcars.

Seven miles down the rail line, others grunted and pul ed in two-man teams fel ing mahogany behemoths with long buck saws. The trunks of these ironlike hardwoods were so wide that when lying on their sides some were tal er than the lumberjacks. The giant logs were shipped by train to the Japanese outpost at Anibogan and then floated downstream on the Tuganay River to the same saw mil whose pier the

Erie

Maru

had tied up to.