Essence and Alchemy (23 page)

Read Essence and Alchemy Online

Authors: Mandy Aftel

In sixteenth-century London, wealthy women bathed and gossiped together in “stews,” sitting in water as hot as they could stand while herb-infused water was piped in from below. By the eighteenth century, perfumed baths had become popular among patricians and prostitutes alike. They were prepared with milk or almond paste, or even champagne, for its luxuriously stimulating effects. For perfuming and stimulating the genitals, there were two kinds of perfumed baths, a dry one on a bed of flowers in a heated tub, and a real bath in a tub of warm water, to which handfuls of violets and wild thyme were added.

From the accounts, the single-sex baths often sound sexier than the coed arrangements. Women bathing together can create a tone of indolent sensuality or precoital preening, invoking the atmosphere of the harem. Even secondhand, the description of a mid-nineteenth-century Turkish women's bath

124

by an Englishwoman whose husband was stationed in that country is sensual in the extreme: “She described vividly how she was initially hypnotized by the atmosphere, the pall of dense, sulfurous steam that almost suffocated her, the sharp, savage cries of the slaves echoing round the domes, the muffled laughter and whispered conversations of their mistresses.” She recalled “the overwhelming effect on her of nearly three hundred half-naked women, draped in fine linen so wet it clung to their bodies; busy slaves stripped to the waist, arms crossed, balancing on their heads piles of embroidered and fringed towels; groups of pretty girls laughing and chattering as they ate confectionery and drank iced fruit juice and lemonade; children playing together. And later, women reclining on sofas as slaves enveloped them in warm linen, poured essences on their hair, and sprinkled their face and hands with perfumed water.”

124

by an Englishwoman whose husband was stationed in that country is sensual in the extreme: “She described vividly how she was initially hypnotized by the atmosphere, the pall of dense, sulfurous steam that almost suffocated her, the sharp, savage cries of the slaves echoing round the domes, the muffled laughter and whispered conversations of their mistresses.” She recalled “the overwhelming effect on her of nearly three hundred half-naked women, draped in fine linen so wet it clung to their bodies; busy slaves stripped to the waist, arms crossed, balancing on their heads piles of embroidered and fringed towels; groups of pretty girls laughing and chattering as they ate confectionery and drank iced fruit juice and lemonade; children playing together. And later, women reclining on sofas as slaves enveloped them in warm linen, poured essences on their hair, and sprinkled their face and hands with perfumed water.”

Still, being naked with the same sex doesn't match the erotic tension of men and women bathing together half clad, at least in the image conjured by a description of a visit to Baden-Baden

125

in the

mid-fifteenth century: “The men wore short drawers and the women loose, low-necked wraps. Walking round the gallery above the woman's pool, the Italians threw down coins for the prettiest, so that when they bent to pick them up, their gowns gaped open revealing all their charms.”

125

in the

mid-fifteenth century: “The men wore short drawers and the women loose, low-necked wraps. Walking round the gallery above the woman's pool, the Italians threw down coins for the prettiest, so that when they bent to pick them up, their gowns gaped open revealing all their charms.”

Solo bathing is an altogether different experience, hearkening back to the rich, painfully pleasurable melancholy evoked by water in nature, as by a favorite sad song. “I always experience

126

the same melancholy in the presence of dormant water,” Bachelard writes, “a very special melancholy whose color is that of a stagnant pond in a rain-soaked forest, a melancholy not oppressive but dreamy, slow and calm. A minute detail in the life of waters often becomes an essential psychological symbol for me. Thus, the odor of water mint calls forth in me a sort of ontological correspondence which makes me believe that life is simply an aroma, that it emanates from a being as an odor emanates from a substance, that a plant growing in a stream must express the soul of water.”

126

the same melancholy in the presence of dormant water,” Bachelard writes, “a very special melancholy whose color is that of a stagnant pond in a rain-soaked forest, a melancholy not oppressive but dreamy, slow and calm. A minute detail in the life of waters often becomes an essential psychological symbol for me. Thus, the odor of water mint calls forth in me a sort of ontological correspondence which makes me believe that life is simply an aroma, that it emanates from a being as an odor emanates from a substance, that a plant growing in a stream must express the soul of water.”

The addition of scent is a link to the synesthetic experience of water in nature that has followed the bath into the privacy of the household and into the bather's consciousness. Perfume heightens the aura of beauty and sanctuary, adds another layer of sensuality that holds you captive. While luxuriating in a scented bath, you can't do anything. You begin to breathe more deeply. Your consciousness disperses into the water and the moist, warm air, much as the fragrance does. You become lost in thought, you lose track of time. The scent of the bath wafts up, surrounding you like a memory. A sheen of oil on the surface of the water recalls a childhood fascination with oil in puddles. You see that it mirrors the colors of the rainbow. You watch how it lies on the surface, unable to merge with the water but adrift upon it. You are reminded of your own essential alonenessâseparate from the water but immersed in it, in transition from one state to another, here and not hereâbut it no longer seems a loneliness.

When you step out of the bath, the scent clings to your body. This fragrant veil accompanies you into the waking world or into your dreams, much like a dream itself. For hours afterward, the flow of your body in space releases scent, reminding you of the bathâand of the alchemy of the bathâwhere all things are possible and none of them need be done. It is enough simply to be.

Â

Â

H

ere are a couple of bath oil blends. The first is an uplifting, stress-reducing blend of fruity and flowery top and middle notes; the second is a relaxing blend of earthy base notes, 15-ml) bottle, preferably one with a screw-on dropper. In order to make best use of the oils, wait until the tub is full, then add a dropperful (around 40 drops) and swish the water around with your hand.

ere are a couple of bath oil blends. The first is an uplifting, stress-reducing blend of fruity and flowery top and middle notes; the second is a relaxing blend of earthy base notes, 15-ml) bottle, preferably one with a screw-on dropper. In order to make best use of the oils, wait until the tub is full, then add a dropperful (around 40 drops) and swish the water around with your hand.

BATH BLEND 1

Â

2 ml (80 drops) bitter orange

2 ml (80 drops) bergamot

2 ml (80 drops) ylang ylang

2 ml (80 drops) geranium

2 ml (80 drops) bois de rose

2 ml (80 drops) bergamot

2 ml (80 drops) ylang ylang

2 ml (80 drops) geranium

2 ml (80 drops) bois de rose

Â

BATH BLEND 2

Â

1 ml (40 drops) labdanum

3 ml (120 drops) benzoin

1 ml (40 drops) patchouli

3 ml (120 drops) clary sage

3 ml (120 drops) bergamot

3 ml (120 drops) benzoin

1 ml (40 drops) patchouli

3 ml (120 drops) clary sage

3 ml (120 drops) bergamot

Here are some more suggestions for scenting the bath:

â¢

Refreshing:

pine needle, sweet orange, lemon, lime, petitgrain, rosemary, juniper berry, fir needle

Refreshing:

pine needle, sweet orange, lemon, lime, petitgrain, rosemary, juniper berry, fir needle

â¢

Calming and relaxing:

cedarwood, chamomile, clary sage, marjoram, neroli, rose, sandalwood, vetiver, ylang ylang

Calming and relaxing:

cedarwood, chamomile, clary sage, marjoram, neroli, rose, sandalwood, vetiver, ylang ylang

To make bath salts: Combine ¾ cup of epsom salts (sold in drugstores to soothe aching muscles) with ¼ cup each of sea salt and baking soda (or just use epsom salts for the full amount). Add 3 ml (120 drops) of essential oils or one of the above blends. Mix well and place in an airtight container. Let the salts absorb the fragrance for one week before using. This is enough for four to six perfumed baths.

Aromatics of the Gods Perfume and the Soul

Thou lovest righteousness, and hatest wickedness: therefore God, thy God, hath anointed thee with the oil of gladness above thy fellows. All thy garments smell of myrrh, and aloes, and cassia, out of the ivory palaces, whereby they have made thee glad.

â

Psalms 45:7â8

Psalms 45:7â8

127

127T

HE OLDEST ROLE of scent, predating its use as a cosmetic, is as a vehicle to the realm of the spirit. And why not? Smell has always been recognized as the most ethereal of the senses. Perfumes are here but not here, of substance and of air, literally conjured out of spirit. Fleeting but embedded in memory, they embody both the evanescent quality of earthly existence and the possibility of eternity. As perfume seems to be the soul of the flower, so the spirit in man has seemed, in all ages, to be the elusive, immortal essence of his mortal body. All that is sacred in the human seems to be most poignantly hinted at in perfume.

The earliestâand most universal and enduringâuse of aromatics in religious rites seems to have been to burn them, for purification, communication with the spirit world, inspiration, and transport of the soul. It lies at the heart of religious practices in nearly every

sect and nationality. The word

perfume

itself comes from the Latin

per fumum,

meaning “through smoke.” Sending up offerings to the gods, in the form of animal sacrifice and incense, was a way to honor the gods for the gifts they had bestowed. Evidence for the use of incense has been found in King Tut's tomb, on ancient figurines of goddesses from the Indus Valley, and in Minoan graves on Crete. An inscription by the pharaoh Ramses II in the grand temple of Ammon at Karnak reads, “I have sacrificed thirty thousand oxen to you, with the highest quantities of herbs and the best perfumes.” Incense is burned in Buddhist ceremonies and as homage to Muslim and Catholic saints alike. Frankincense is a nearly universal ingredient, but other fragrant resins and gums have also been used.

sect and nationality. The word

perfume

itself comes from the Latin

per fumum,

meaning “through smoke.” Sending up offerings to the gods, in the form of animal sacrifice and incense, was a way to honor the gods for the gifts they had bestowed. Evidence for the use of incense has been found in King Tut's tomb, on ancient figurines of goddesses from the Indus Valley, and in Minoan graves on Crete. An inscription by the pharaoh Ramses II in the grand temple of Ammon at Karnak reads, “I have sacrificed thirty thousand oxen to you, with the highest quantities of herbs and the best perfumes.” Incense is burned in Buddhist ceremonies and as homage to Muslim and Catholic saints alike. Frankincense is a nearly universal ingredient, but other fragrant resins and gums have also been used.

The spirals of odorous smoke rise up, so it is instinctive to look upon them as paths to the heavens, speeding one's prayers of exaltation and devotion. The scented smoke that wafted through the temple was also believed to repel harmful spirits and attract good influences. Aromatics were burned in attempts to communicate with the spirit world as wellânot just to send a message but to elicit a response. The priest or priestess, seer or magician, might cover head and face with a cloth to trap the fragrant fumes, inhale them, and grow intoxicated. Inspired in this way, the soul was said to leave the body and travel in a kind of dream state to other realms.

Hindu perfumer

Anointing with fragrant oils and unguents is an equally universal ritual practice, and nearly as old. Myrrh is set down in Exodus as one of the main ingredients of the holy anointing oil of the Jews, along with cassia and cinnamon. Oil of myrrh and other essences figured importantly in the yearlong purification of women as ordained by Jewish law, the ordeal Esther had to undergo before she was presented to King Ahasuerus and won his favor. Sacred objectsâark, candlesticks, altarâas well as people were anointed.

Chrism

128

is a consecrated oilâusually olive oil to which balsams and spices have been addedâthat is used in various Christian rites, including baptism and confirmation, anointing the deceased, and ordaining bishops and priests. “Medieval legend held that the chrism came directly from the scented exudations of the Tree of Life in the Garden of Eden and therefore partook of its vivifying power,” writes cultural historian Constance Classen, noting that the origin of the belief is a statement in the apocryphal Book of Enoch that the “sweet odor” of the Tree shall enter into the bones of the chosen, and they shall live a long life. Thus chrism was thought to confer on those who were baptized with it a degree of spiritual if not physical immortality.

128

is a consecrated oilâusually olive oil to which balsams and spices have been addedâthat is used in various Christian rites, including baptism and confirmation, anointing the deceased, and ordaining bishops and priests. “Medieval legend held that the chrism came directly from the scented exudations of the Tree of Life in the Garden of Eden and therefore partook of its vivifying power,” writes cultural historian Constance Classen, noting that the origin of the belief is a statement in the apocryphal Book of Enoch that the “sweet odor” of the Tree shall enter into the bones of the chosen, and they shall live a long life. Thus chrism was thought to confer on those who were baptized with it a degree of spiritual if not physical immortality.

Quite early in history, anointing became a prerequisite for holiness. Priests and kings were ceremoniously anointed on the occasion of their elevation to positions of divine authority. British royalty are still crowned with full Christian rites, including being anointed with the same amber-colored blend of rose, orange blossom, jasmine, cinnamon, benzoin, civet, musk, ambergris, and sesame oil that has been used since the ascension of Charles I.

Anointing the body was an obligatory part of the initiation ceremonies and magic festivals of most primitive peoples. Most of them

believed that sacred oil was a divine substance that imparted its supernatural qualities to the wearer when it was rubbed on the body. A headhunter, for example, might anoint his head with fragrant oils after he had captured his first trophy, to reinforce his bodily strength.

believed that sacred oil was a divine substance that imparted its supernatural qualities to the wearer when it was rubbed on the body. A headhunter, for example, might anoint his head with fragrant oils after he had captured his first trophy, to reinforce his bodily strength.

To speak of any of these practices as religious rites is in a sense a mischaracterization. All of them derive from a time when body, mind, and spirit were seen as indivisible and were ministered to as such by priests, sorcerers, and shamansâamong whom it was also impossible to differentiate absolutely. Aromatic spices and herbs were seen as magical preparations that addressed a person's psychological and spiritual as well as physical ailments in what we would call a “holistic” fashion. A prime example of such a panacea is

kyphi,

the famous ancient Egyptian perfume composed of as many as sixteen ingredients, including cardamom, spikenard, cinnamon, saffron, frankincense, myrrh, raisins, wine, and honey.

Kyphi

could be dissolved in water and swallowed as a remedy, or burned as incense in an offering to the gods. It was reputed to cleanse the body, soothe the spirit, sweeten the breath, restore powers of imagination, induce sleep, and make one receptive to dreams.

kyphi,

the famous ancient Egyptian perfume composed of as many as sixteen ingredients, including cardamom, spikenard, cinnamon, saffron, frankincense, myrrh, raisins, wine, and honey.

Kyphi

could be dissolved in water and swallowed as a remedy, or burned as incense in an offering to the gods. It was reputed to cleanse the body, soothe the spirit, sweeten the breath, restore powers of imagination, induce sleep, and make one receptive to dreams.

There was a sacred dimension to the healing arts, and early medicine in turn was bound up in magic, spells, and prayers. Disease was looked upon as a disharmony between the spirit world and the human world. Scented oils were employed for the expulsion of demons and became an adjunct of preventive medicine. Priests functioned as perfumers, formulating and blending aromatics and ointments for the rich, who alone could afford them.

It took a long while for these allied traditions to sort themselves into separate strands, and occultists, perfumers, physicians, and religious practitioners continued for some time to draw upon their common origins. “Throughout the sixteenth

129

and seventeenth centuries very many occultists continued to use aromatics as their pagan forbears had done before them,” writes Eric Maple, an expert on magic and perfume. “There were, however, certain areas of activity where the professions of magician and perfumer tended to overlap. A perfumer's shop in seventeenth-century Paris was apparently almost indistinguishable from the chamber of a sorcerer. It was often decorated with dried mummies and stuffed ibises, perhaps as a reminder to the fashionable clientele that aromatics had once been a highly developed subtlety of Egyptian magic. Most perfumers must have been well aware of the close connection between sexual allure and the occult, for they illuminated their establishments with special lamps which cast an eerie glow over the scene.”

129

and seventeenth centuries very many occultists continued to use aromatics as their pagan forbears had done before them,” writes Eric Maple, an expert on magic and perfume. “There were, however, certain areas of activity where the professions of magician and perfumer tended to overlap. A perfumer's shop in seventeenth-century Paris was apparently almost indistinguishable from the chamber of a sorcerer. It was often decorated with dried mummies and stuffed ibises, perhaps as a reminder to the fashionable clientele that aromatics had once been a highly developed subtlety of Egyptian magic. Most perfumers must have been well aware of the close connection between sexual allure and the occult, for they illuminated their establishments with special lamps which cast an eerie glow over the scene.”

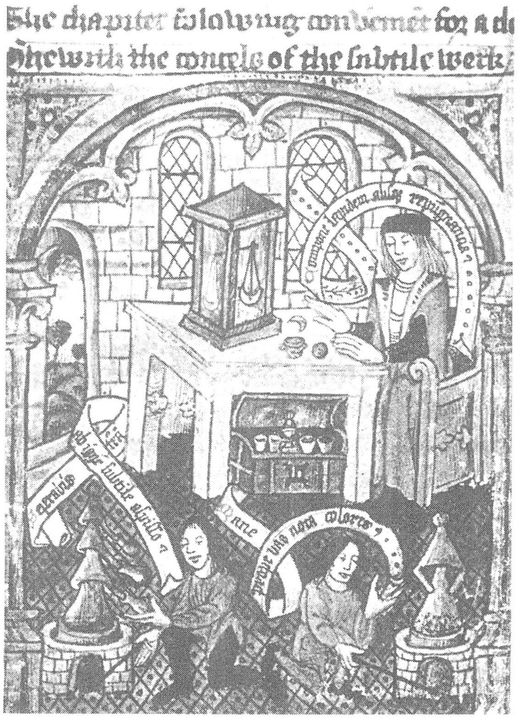

Medieval English perfumer's shop, with stills

A

ccording to Plutarch, the river Lethe emitted “a delicate and suave exhalation of strangely voluptuous odors, causing an intoxication like that achieved by becoming drunk on wine.” Paradise is described in tradition after tradition as a place filled with exquisite odors. In other words, beautiful scent has long been considered not only a pathway to but an emanation of the sacred. As we have noted, this belief has led people to scent their places of worship, often in ingenious ways, like the Arabs who mixed musk with mortar so that their mosque might exhale a divine and everlasting scent.

ccording to Plutarch, the river Lethe emitted “a delicate and suave exhalation of strangely voluptuous odors, causing an intoxication like that achieved by becoming drunk on wine.” Paradise is described in tradition after tradition as a place filled with exquisite odors. In other words, beautiful scent has long been considered not only a pathway to but an emanation of the sacred. As we have noted, this belief has led people to scent their places of worship, often in ingenious ways, like the Arabs who mixed musk with mortar so that their mosque might exhale a divine and everlasting scent.

The gods and goddesses of many religions are represented as spreading perfume, an effluence of their divine grace and loveliness. Krishna is said to exude the odor of celestial flowers. Hippolites, in one of the tragedies of Euripides, exclaims, “O Diana, I know that thou art near me, for I have recognized thy balmy odor.” In fact, some authorities on ancient religions say that the object of using incense in worship was to impart the odor of the god.

In Christian tradition, the sweet smell of sanctity was extended to the saints, who were supposed to wear their lovely scent as a badge of their holiness and purity. Teresa of Avila was believed to emit such a powerful fragrance that it perfumed everything she touched.

Saint Polycarp was said to be so steeped in the odor of Christ that it seemed he had been anointed with perfumed unguents. “That the human body

130

may by nature not have an overtly unpleasant odor is possible, but that it should actually have a pleasing smellâthat is beyond nature,” wrote Pope Benedict XIV. “If such an agreeable odor exists, whether there does or does not exist a natural cause capable of producing it, it must be owing to some higher cause and thus deemed miraculous.”

Saint Polycarp was said to be so steeped in the odor of Christ that it seemed he had been anointed with perfumed unguents. “That the human body

130

may by nature not have an overtly unpleasant odor is possible, but that it should actually have a pleasing smellâthat is beyond nature,” wrote Pope Benedict XIV. “If such an agreeable odor exists, whether there does or does not exist a natural cause capable of producing it, it must be owing to some higher cause and thus deemed miraculous.”

The sweet fragrance of the saint was evidence of a special relationship to God. As Annick Le Guérer observes:

It also serves

131

as both a means and an end. Spiritual awareness and asceticism tend to separate a human being from man's baser, animal nature and therefore from the odors linked with corruption and decay. At the same time, the sublimation of organic needs and the elevation of a soul focused totally on the other world enable the saint to partake of the perfume of the Divinity. Both an offering to God and a gift from Him, the odor of sanctity is, for ordinary mortals, a sign of the singular nature of the creature emitting it. Because an odor of sanctity is the special attribute of a person who has renounced the flesh and its desires, however, it is an offering as well. By immolating the body the saint draws nearer to God, but rather than making a blood offering, he or she substitutes the odor of a body sanctified through penitence.

131

as both a means and an end. Spiritual awareness and asceticism tend to separate a human being from man's baser, animal nature and therefore from the odors linked with corruption and decay. At the same time, the sublimation of organic needs and the elevation of a soul focused totally on the other world enable the saint to partake of the perfume of the Divinity. Both an offering to God and a gift from Him, the odor of sanctity is, for ordinary mortals, a sign of the singular nature of the creature emitting it. Because an odor of sanctity is the special attribute of a person who has renounced the flesh and its desires, however, it is an offering as well. By immolating the body the saint draws nearer to God, but rather than making a blood offering, he or she substitutes the odor of a body sanctified through penitence.

In some traditions, even mere mortals are believed capable of attaining the aroma of righteousnessâposthumously, that is, and if they are sufficiently pure of soul. In his

History of Prince Arthur,

Sir Thomas Mallory tells how Sir Lancelot's companions, having found him dead, noticed “the sweetest savor about him.” The Persians thought that perfumed breezes imbued the dead with fragrance as

they approached paradise. Others held that the soul required a beautiful scent in order to break clear of the body and begin its ascent. The Aztecs offered perfumed flowers for four years after death, which was said to be the amount of time it took for a soul to reach heaven.

History of Prince Arthur,

Sir Thomas Mallory tells how Sir Lancelot's companions, having found him dead, noticed “the sweetest savor about him.” The Persians thought that perfumed breezes imbued the dead with fragrance as

they approached paradise. Others held that the soul required a beautiful scent in order to break clear of the body and begin its ascent. The Aztecs offered perfumed flowers for four years after death, which was said to be the amount of time it took for a soul to reach heaven.

Other books

Revenge Wears Rubies by Bernard, Renee

Shelby by McCormack, Pete;

The Sweet Spot by Laura Drake

At the Villa Rose by AEW Mason

The Deepest Water by Kate Wilhelm

The Fuller's Apprentice (The Chronicles of Tevenar Book 1) by Angela Holder

Dreamer by Charles Johnson

The Ruby Talisman by Belinda Murrell

Addicted to Him by Lauren Dodd

The Godson by Robert G. Barrett