Authors: Dee Gordon

Essex Land Girls (4 page)

Appreciation and accolades for the members of the WLA came from diverse sources, right up to the very top, but took time to have any effect. Representatives of the WLA visited Buckingham Palace on Tuesday, 19 March 1918, preceded by a procession featuring a hay wagon with two fine horses from an Essex farm (according to the

Chelmsford Chronicle

). The girls were the guests of Lady Denman at a vegetarian luncheon, and were subjected to an informal inspection by Queen Mary.

Seed growers at Bocking Hall Farm, West Mersea, 1918. Note the

armbands in memory of those who lost their lives in the First World War. (Courtesy of Ron Green’s collection at Mersea Museum)

In the summer of 1917, a Women’s Farm Competition was organised by the Hertfordshire and Essex Women’s War Agricultural Committees, and took place in Bishop’s Stortford, just over the Hertfordshire/Essex border, with competitors from a dozen counties in scorching sunshine. An account in the 1 August issue of the

Illustrated War News

reads:

Probably not a few farmers in the country today are wishing that they had not been quite so hasty in letting prejudice against women’s work over-ride their own common sense. [This] competition was not only the biggest, but easily the most successful, demonstration of women’s farm work ever held in the country. From eleven o’clock onwards, women from all parts of England gave practical proof of their skill in all branches of work connected with farming. One is apt to think of farm girls as the picturesque sun-bonneted maidens with whom we are familiar on the musical-comedy stage. But pretty as the sun-bonnets and immaculate prints were, the drab-coloured breeches and gaiters with the covering tunic affected by the girl on the land today are equally attractive if a little less picturesque. But then carting manure, harnessing horses to carts and harrows, hoeing, killing poultry, and milking, are more serious pursuits than usual for the musical-comedy land girl.

The judges of the competition were ‘sturdy farmers from Hertfordshire and Essex, who confessed themselves frankly delighted with the high standard achieved by so many of the competitors’. Events included ‘carting, tilting, laying out manure, driving a cart between rows of pegs that made very little allowance for errors of judgment, hoeing roots, ditching and hedge-trimming, harrowing, harnessing, poultry killing and plucking, and milking strange cows embarrassed at the publicity of the ordeal, with as much coolness and absence of fuss as if they had never done anything else’. The workers were described as ‘sunburnt and freckled, attractive and picturesque’ striding about ‘in their workmanlike get-up with their hair tucked away under a wide-awake [a hat with brim and low crown, wittily so called because it didn’t have a nap …], a handkerchief, or a sunbonnet’. There are references to the range of backgrounds of the girls – ‘university women, domestic servants’ – and to the ‘very small’ percentage of women who relinquish the work ‘on account of physical incapacity to carry it on’.

In spite of the hazards of the work, one Land Army Girl in Essex managed to do more serious damage simply by falling off her bicycle in September 1919. This was Rose Thorne, aged 22, living then at Broomfield Road in Chelmsford. She sustained a fractured leg, a nasty injury, which was reported in the

Essex Newsman.

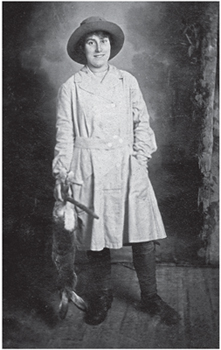

Alice Walker

, born towards the end of the nineteenth century, was at Langdon Hall near Dunton, working in domestic service like so many of her age, at the outbreak of war. She broke away from this environment by signing on as a Land Army Girl and worked at local farms: primarily, it seems, Blue House Farm and latterly Rose Farm, in Laindon. Although from a rural area, she had no farming experience, and worked with the animals, learning to milk the cows and churn the butter, all by hand. She also learned to shoot local vermin, a threat to the food crops, including rabbits – as evidenced by this image of her in uniform complete with shotgun. (‘Excess rabbits’ were mentioned at Norsey Wood, Billericay, in the minutes of one of the 1918 meetings of the Agricultural Executive Committee.) Alice’s experiences gained her a husband, because in 1919 she married the farmer’s son, George Walker, and the couple lived and farmed out of Rose Farm. Her memories were passed to her great-niece, Margaret King from Benfleet, who actually saw the butter churn as a youngster but wasn’t able to turn the handle.

Alice Walker (née Stenning), in the Laindon area, 1917. (Courtesy of Edmund King)

Another Land Army Girl at Blue House Farm was Lynette Ashley. Her story is recounted in

Laindon in the Great War

. Starting time for Lynette was apparently 4.30 a.m., with a walk across the fields while eating large slices of bread and jam. Her main task was getting the herd of cattle in for milking in time for the 7 a.m. train to London, delivered by horse and cart to Laindon Station at breakneck speed. At calmer moments, with the cows chewing the cud, falling asleep caused her an occasional scare in case the herd had wandered off.

Born in 1895,

Doris Robinson

recorded an account (for the Imperial War Museum) of working ‘for a strange man’ on a ‘farm in Loughton’ after just two weeks’ training at Little Baddow. Here she ‘looked after seven jersey cows, 400 hens, goats and ducks’ on her own! There were some extra staff employed ‘at haymaking’ but there were ‘no days off, even on Christmas day’ when she was ‘given mouldy fruit as a Christmas gift’.

The only reference she made to her uniform was to the armbands she wore, but she refers to her ‘lodgings with the carpenter and his wife, paying them 18

s

per week out of my £1 per week pay’, with another 3

d

payable for insurance. These lodgings were described as a ‘large house with nowhere to wash except in the cowshed’, but she stayed there for two years until marrying in 1917. She ‘enjoyed working with animals’ and ‘rode a pony, using a sack, not a saddle’. Originally from Rochdale, Doris had decided that the WLA was easier than nursing – her original choice, but with ‘too many questions’ she couldn’t answer!

She spoke of the ‘bath in the greenhouse’ and the danger of ‘climbing ladders’ and the pain of chilblains as a result of the cold. Although ‘left to my own devices’, she was not unhappy because she ‘was surrounded by creatures … I even enjoyed rounding up the ducks’.

Annie Russell

from Little Horkesley was born in 1903 and lived on the family farm at Boxted, where she helped out as a very young member of the WLA. Her daughter felt she was well suited to the tough tasks involved, and in an interview for the Southend

Echo

(30 July 2014), described Annie as ‘very good with horses’. She learnt to plough ‘as well as any man with a team of two heavy horses’. Her father, the farm bailiff, would trust no one else to ‘hold a horse’ if it needed medical treatment. ‘The most important duty she had was to drive the pony and trap to North Station, Colchester, to collect the rations for the German prisoners of war who had been sent to work on the farm.’ Apparently, ‘her father always knew if she had whipped the horse up the hill on her way home, and she would get into a lot of trouble for this’. Annie could ‘lay a hedge, prune fruit trees, rotate crops’, knew all about harvesting, was aware of the importance of deep drained ditches to keep the land in good condition, and the conservation of the rainfall to avoid flooding. Although fond of animals, she could ‘wring a chicken’s neck and hit a rabbit on the back of the head’.

Annie Russell (née Balls), aged around 14, in Boxted area,

c.

1917 (Courtesy of Pauline Taylor)

A very detailed account was produced by Southampton Museum in 1983 for an oral history project. This was provided by

Olive Crosswell

from Great Baddow who joined the Land Army at nearby Chelmsford between 1917 and 1918. She received her training ‘on the job’, i.e. on the farm.

One of the first things she learned was how to milk a cow, and she points out that if you were ‘the first to go’ then you were working with a ‘dry cow’ and this made it even more difficult for someone with no experience, and resulted in swollen arms and wrists. If you managed to get a froth on the milk, that meant you were ‘doing well’. She remembers one cow kicking the ‘first lot of good milk’ into the gully, to her obvious dismay. Milk had to be put through the cooler (which looked to her like a washboard), and into a separator to divide the cream and milk. Turning the butter churn was one of the best jobs, achieving gorgeous results.

Apart from the milking, Olive was involved in general farm work and was moved around a lot, though most of the farms she remembers were in Essex. She cut hay and tied it into stooks from around 6 a.m. to 10 a.m., following this up with muck spreading and feeding the horses and/or cows, depending on the farm. She also used a harvester and a big scythe for cutting edges (dangerous work it seems), and loaded up the pony carts. When one such pony got himself stuck in a gate, the farmer swore at her, and she felt that he (and others) were not happy with being fobbed off with Land Girls rather than ‘proper’ farm workers. One farmer also objected to her being given a glass of milk, declaring that it should have been water. But the nastiest incident she remembers was more painful: the time she went flying through the door to the cow-house yard and ended up on her rear, bursting one of several unpleasant boils! This put her in bed for the afternoon, and she had to explain the embarrassing experience to her overseer when she didn’t turn up to feed the pigs, who had begun protesting in a very noisy fashion. The wound was bound up in a strip torn from her chemise and she was at work the next morning.

Olive admitted that she did occasionally need help from the few men that were left working on the farms. For instance, when in Bentley (there are two Bentleys in Essex, but which one is not defined) she had been trying to get a pony into its trap when it broke away. Her hair ribbon flew off as she struggled to hang on, but passing workers stood with their arms out and the pony stopped and calmed down, a literally hair-raising experience. ‘At least it wasn’t the stallion,’ she recalls, ‘he was kept for breeding, and was a very noisy animal which I had to feed.’ The same pony, named Punch, refused to increase his pace when going downhill; he would be completely oblivious to any of the rural noises around him but a piece of fluttering paper could frighten him and then he would pick up speed inordinately.

At one farm, Olive also had to tend a couple of goats, one male and one pregnant female. She claims that seeing the birth of that goat put her off having a baby of her own! It was not unusual for two people to have to hold down one goat before it would stand still long enough to be milked.

She also worked on a market garden in Essex, described as being ‘opposite a Royal Artillery Camp’ (of which there were several) and was amazed to see a woman farmer who smoked and rolled her own. She had ‘never seen a lady smoking’ before. She hung on to a black cigarette given to her by one of the troops while at the market garden and she still had it in the 1980s. An advantage of this particular job was that she was able to take home – i.e. to her billet – spring onions and radishes, and also give some to the soldiers in the camp. A disadvantage was scrubbing the plant pots in cold water in the winter. Another memory was: