Evacuee Boys (25 page)

Authors: John E. Forbat

These periods were interspersed with team games requiring quick thinking, lots of running and jumping and the absolute favourite – British Bulldog. With boys’ ages ranging from 11, through to hefty 17- and 18-year-olds nearly ready for military call-up, the game started with one boy in the middle of the hall and everybody else at one end. On the signal, we had to run to the other end and try to avoid being caught and lifted off the ground by the one in the middle. Once thus caught, we remained in the middle and helped to stop the rush on the next signal to run back. Each catch involved a lively struggle and gradually the number of runners reduced ’til eventually a last one remained, to brave the gauntlet through the whole troop barring the way in the middle. This would be one of the biggest, toughest lads and, by the time I was 16 or so, I prided myself on getting through more than once. Mother fulfilled the all-too-frequent duty of resuscitating my uniform to patrol inspection standards.

Like most boys, I was sometimes late for school. Everybody was late sometimes and at assembly, after the headmaster had announced who had been killed in the previous night’s raids, the late boys were paraded for their punishment. As a Jewish boy, I was excused attending assembly without suffering any cultural or other traumas. When I became a prefect, and it was customary for prefects to take turns at reading the lesson, I joined in and read from the Old Testament. I still demurred from joining in the prayers and, sitting on the prefects’ bench, the other kids joined in the joke when they saw my hymnbook held accidentally-on-purpose upside down.

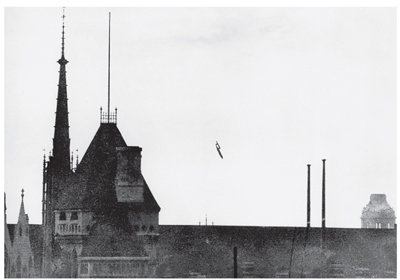

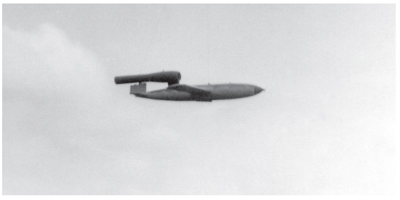

Doodlebugs over the Law Courts, London. (By kind permission of Mr Phillip Jarrett)

I must have been 15 when the doodlebug flying bombs began to rain down at all hours. One of the first passed right over our heads as Andrew and I were cycling into Kent one Friday evening for one of our many weekend Scout camps. The A2 ran dead-straight south-east and the throaty ramjet roared ever louder as it approached to fly, rather low, directly overhead. Flak was bursting all around it – quite a spectacular show – ’til the shrapnel started to bounce off the pavement around us and we ducked into a doorway, later burning our fingers collecting the hot shards.

On the way home on Sunday, we passed the Streatham house of a good friend who was old enough to have been called up for Service. Their front door was missing and all their windows were blown in, so Mrs Randall asked us to go to her sister who lived near us in London, to tell her they were OK. We got back onto our bikes and passed the cause of the Randalls’ damage – a whole block of houses flattened by a single doodlebug, leaving little more than a big crater. We cycled on past our flats towards the Randalls’ relatives in Hammersmith and, racing north as the sirens wailed, we heard another throaty roar rapidly approaching. We had been trained to wait until the engine cut, then to lie down in the gutter with our hands covering our heads. The doodlebugs then pitched down to dive onto wherever they were pointing. It cut out very close to us, so we leapt off our bikes, dived for the kerb and waited.

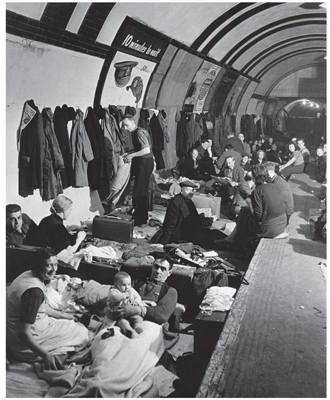

A great mushroom cloud rose where it had hit in the next street and we got back up. Before we could pass on the Randalls’ message, Andrew, who had started medical school by then, tarried to render first aid. In the months while the doodlebug campaign persisted, the air-raid sirens sounded just about every few minutes. Most people ran into air-raid shelters – often down into the Underground, where at night many slept on the platforms – but as many doodlebugs came during the day as at night. Our flats had a big basement that was used as a shelter, we boys only used it to practice our table tennis, however, and it was otherwise unused. As Mother found out only after the war was over, being up on the roof was more exciting during air raids.

The frequency of air-raid warnings got so high that taking heed would completely prevent all normal activity and, for the first time in my school days, I determined

never

to be late. No way was I going to let Hitler dominate my life any longer! Air-raid warning or not, I rode to Sloane school and thumbing my nose at Hitler, without fail arrived on time every day. When the V2 rockets began to fall from their trajectory into space, there was no warning and no way to hide anyway. Once you heard the explosion – followed by the whine of its supersonic arrival – it was obvious that some other poor bastard had bought it.

Sheltering from bombing in a West End London Underground station. (Wikimedia Commons/FDR Library, New York)

I wrote more applications, tried with the BBC without success. I listened to some of the Hungarian broadcasts and I did not like them and shared my objections. They thanked me, asked me to follow their broadcasts with attention and to pass on my observations. Since, as an enemy alien I was not allowed to possess a radio, I wrote to the Home Office, asked them to change my enemy alien status, since my every personal interest was tied to the British State, and I enclosed my correspondence with the BBC. One morning, they called me to the police and the officer said: ‘You want a radio?’ I replied that that was a peripheral question, I do not want to be an enemy alien and then I would automatically be able to have a radio. He was very unfriendly, interrogated me in detail about my family and everything else. When he asked about Uncle Eugene, I said he was English. Sarcastically he replied, ‘He is only naturalized British, he will not be English as long as he lives.’ I was upset by the unusual lack of courtesy on the part of the police and when he said I could have a radio if I wanted to, but they would not change my status as enemy alien, I said, thank you, then I do not want a radio either.

By this time, Andrew had finished his preliminary studies at Chelsea Polytechnic and he had to find a place in a medical school. We went from one hospital to another, sent applications with the very best test scores and recommendation from wherever he had studied, but all said that they had no more vacancies. Finally I got [him] an interview with the Dean of the Guy’s Hospital Medical School, who said that they had one position for which there were seven or eight applicants. They would hold an examination and the best would get the place. Andrew took the test and he was among the first twelve for whom there were places. The Dean informed me regretfully, that I should understand that they had to give preference to English applicants. It seemed hopeless for our poor son to be able to continue his studies. The next day there was an unexpected message from University College, where Andrew had also applied, that one of their applicants had withdrawn and they would accept Andrew. This was an unexpected bit of luck and we were now at peace that our son could become a doctor. The college was evacuated to Leatherhead, about an hour from London. Since we did not have money to get him lodgings there, he travelled there daily. As the bombing became lighter and the war was becoming more hopeful, we wanted to bring Johnny home as well, to the regret of his teachers who were very fond of him. I went to the principal of a school in London – it was not free, one had to pay a small tuition fee – and when I showed him Johnny’s report and recommendations from his teachers, he decided that they would admit Johnny for the following term to begin three months later. So, we would all be together again after Christmas.

Poor thing, Mum left the house early to open the Pop Inn and I stayed at home with her mother. Sometimes she cooked my mid-day dinner and I did not like it. She could not cook nearly as wonderfully as Mum, since she, with her precision, was transformed into a most outstanding cook by then. I was prejudiced against her mother’s pride of being Italian. I hated Italians as much as I knew in my feelings since the Italians who were our allies before the First World War, stabbed us in the back, and attacked us and now also, on the other side in the Second World War.

One evening I went home, thinking that Mum would already be there, but she was not. I waited a while, then I went down to the Underground station across the road. One train came after another – without her. When she was not in the last one, I got very anxious. I phoned the Pop Inn, with the knowledge that there would be no reply, since at that time it was usually closed. To my surprise, Uncle Eugene answered. There was something peculiar in his voice and manner of speaking. He said, there was nothing special, but Mum was not feeling well and they put her on the sofa until she felt better. I could not imagine what her trouble could be, I was restless, but Uncle Eugene said that she was better, I should wait at home and he would bring Mum home shortly. I walked up and down like a madman outside the gate, went up to the flat, went down again until at last at 2:30 a.m. a taxi drew up at the by the gate. Uncle Eugene and a strange woman emerged and they lifted Mum out. Uncle Eugene tried to calm me down that there was no trouble. She was deadly pale and could not speak or stand on her feet. That is how we took her upstairs, undressed her and put her to bed. It came out that Mum had collapsed, she had hardly any pulse, her heart was racing like on one occasion before Andrew was born when we were frightened. The three and a half years of excessive work twelve hours daily and sometimes more, standing on her feet the whole day had taken their toll. The woman with her was a stranger, who happened to be in the Pop Inn; since she was a nurse, she took care of her. She stayed the night; the three of us lay dressed in the bed, until slowly she came to herself. Next day the doctor came early in the morning and ordered complete peace and rest. In a few days, with God’s help Mum collected yourself and I decided that she would leave the work at the Pop Inn.

30

July

1944

– from Scout camp near Thorpe, Surrey

My darlings,

Just a line to let you know that I am well. John has not arrived yet (4 p.m.) but I will get him to add a few words when he does.

I was rather late getting here, because I got a puncture on the way, & my attempts to mend it were not successful. I did not walk. I rode on a flat tyre & thus my progress was somewhat slower.

We had quite a bit of sunshine this morning, but it is pouring with rain now. Of course we are quite dry inside the tents. I am writing sitting on the Ambulance Kit as a chair & a patrol-box as a table & the store-tent as my office.

There is no more news as yet, except that I have examined nearly every boy’s chest.

With love to all, with special regards to Noni,

Lots of kisses

Andrew

… continued by John

Dear Mum & Dad,

I arrived O.K. at about 5 o’ clock and I’m having a good time. We play cricket a lot and we are going into Windsor this afternoon probably for swimming.

Cheerio & love to all,

John

![]()