Evolution (10 page)

With a sudden stab of loss, Listener hurled her spear into the ocean. It disappeared into the water’s glimmering mass.

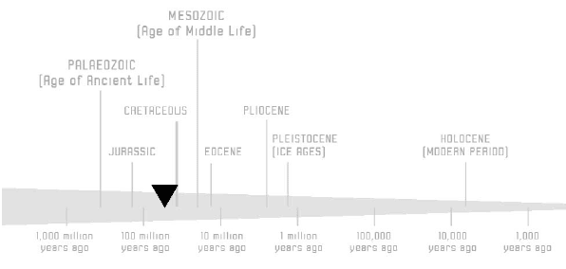

North America. Circa 65 million years before present.

Once interplanetary impacts had been constructive, a force for good.

Earth had formed close to the brightening sun. Water and other volatiles had quickly boiled away, leaving the young world an empty theater of rock. But the comets, falling in from the outer system, delivered substances that had coalesced in that cooler region: especially the water that would fill Earth’s oceans, and compounds of carbon, whose chain-based chemistry would lie at the heart of all life. Earth settled down to a long chemical age in which complex organic molecules were manufactured in the mindless churning of the new oceans. It was a long prelude to life. It would not have come about without the comets.

But now the time of the impacts was done, so it seemed. In the new solar system, the remaining planets and moons followed nearly circular orbits, like a vast piece of clockwork. Any objects following more disorderly paths had mostly been removed.

Mostly.

The thing that now came out of the dark, its surface of dirty slush sputtering in the sun’s heat, was like a memory of Earth’s traumatic formation.

Or a bad dream.

In human times, the Yucatan Peninsula was a tongue of land that pushed north out of Mexico into the gulf. On the peninsula’s northern coast there was a small fishing harbor called Puerto Chicxulub (

Chic-shoe-lube

). It was an unprepossessing place, a limestone plain littered with sinkholes and freshwater springs, agave plantations, and brush.

Sixty-five million years before that, in the moist age of the dinosaurs, this place was ocean floor. The plains of the Gulf of Mexico were flooded up to the foothills of the Sierra Madre Oriental. The shallow Yucatan Peninsula itself lay under nearly a hundred meters of water. The sediments that would later form Cuba and Haiti were part of the deep seafloor, yet to be lifted by fault movements to the surface.

In an age dominated by warm shallow seas, drowned Chicxulub was an unremarkable place. But it was here that a world would end.

Chicxulub is a Mayan word, an ancient word coined by a lost people. Later, when the Mayans were gone, nobody would know for sure how it translated. Local legend said it meant the Devil’s Tail.

In its last moments the comet flew in from the southeast, passing over the Atlantic and South America.

In bright, shallow waters the huge ammonite cruised.

This sea-bottom hunter, the size of a tractor tire, looked something like a giant snail, with an elaborately curved spiral shell from which arms and a head protruded cautiously. As it had grown, it had extended its shell’s spiral structure, gradually moving from one chamber outwards to the next; now the linked, abandoned chambers were used for buoyancy and control.

The ammonite moved with surprising grace, its upright spiral cutting through the waters. And it scanned its surroundings with wide intelligent eyes.

The sunlit sea was crowded, translucent, full of rich plankton. Some of the creatures here— oysters, clams, many species of fish— would have been familiar to humans. But others would not: there were many ancient species of squid, the ammonite itself— and, dimly visible as shadows passing through the blue reaches of the deeper ocean— giant marine reptiles, mosasaurs and plesiosaurs, the dolphins and whales of the age.

As the daylight gathered, more of the ammonite’s kind were rising, to hang like bells in the translucent water.

But the ammonite spotted movement on the seabed. It descended quickly, sensory tentacles pushing out of its shell. By sight and feel it quickly determined that the scuttling, burrowing thing in the gritty sand was a crab. More arms slid out of the shell and wrapped around the crustacean, tiny hooks on each arm helping to secure their grip. The crab was pulled easily away from the soft seabed. A heavy birdlike beak protruded, and the ammonite bit through the crab’s shell, between its eyes. It injected digestive juices into the shell, and began to suck out the resulting soup.

As particles of meat diffused in the water, more ammonites came sliding in.

But the ammonite with the crab saw a shadow moving above, a shadow with a snout and fins, silently sliding, rapidly resolving. It was an elasmosaur; a marine reptile, a kind of plesiosaur with an immensely long neck. Abandoning its kill, the ammonite ducked into its shell. The opening in the shell was immediately sealed off with a heavy cap of hardened tissue.

The elasmosaur fell on the ammonite, pushed its shell over, and clamped its powerful jaws around the narrowest part of the spiral. But it could not break through. After breaking a cluster of teeth, the elasmosaur dropped the shell, letting it drift back to the ocean floor. Frustration and pain seethed in its one-dimensional awareness.

The ammonite had endured violent shaking, but it was safe in its armored home.

But one immature ammonite had not been so wary. It tried to flee, its jets pushing it this way and that.

The elasmosaur took its consolation kill well. Its teeth sliced expertly across the spiral shell at the place where the body was attached to the inner surface. Then it shook the shell hard until the ammonite, still alive, tumbled out into the water, naked for the first time in its life. The fish-lizard took its prize in a single gulp.

Now the elasmosaur spotted a cloud in the water. It plunged in without hesitating.

The cloud was a shoal of belemnites, thousands strong. The little squid had gathered for protection, and their defensive systems, of sentries and ink and shimmying, deceptive movements, were usually effective even against predators as fast as this elasmosaur. But they had been caught out by this creature’s angry lunge. They darted away, venting ink furiously at the immense invader, or even leaping out of the ocean altogether and into the comet-bright air. Still, hundreds of them died: each a pinpoint of awareness, each of them in its way unrepeatable and unique.

Meanwhile, cautiously, the crab-killer ammonite had opened its shell once more. A tube of muscle protruded from the opening, and a high-pressure stream of water pulsed out, jetting the ammonite up and into the blue waters. It had lost the crab. But no matter. There was always another kill to make.

So it went. It was a time of savage predation, in the sea as on land. Mollusks hunted ammonites, boring through shells, poisoning prey animals, and firing deadly darts. In response, bivalves had learned to bury themselves deep in sediment, or had evolved spines and massive shells to deter attackers. Limpets and barnacles had forsaken the deep sea, colonizing shallow environments on the shore where only the most determined of hunters could reach them.

Meanwhile, the seas teemed with predatory reptiles. Carnivorous turtles and long-necked plesiosaurs fed on fishes and ammonites— as did pterosaurs, flying reptiles who had learned to dive for the riches of the ocean. And huge, heavy-jawed pliosaurs preyed on the predators. Measuring some twenty-five meters long, with jaws alone some three meters long, their sole stratagem to rip and shake their prey apart, the pliosaurs were the largest carnivores in the history of the planet.

The rich Cretaceous oceans teemed, enacting a three-dimensional ballet of hunter and hunted, of life and death. It had been so for tens of millions of years. But now a bright light was building above the glimmering surface of the ocean, as if the sun were falling from the sky.

The ammonite’s eye was drawn upwards. The ammonite was smart enough to feel something like curiosity. This was new. What could it be? Caution prevailed: Novelty usually equated to danger. Once more the ammonite began to withdraw into its shell.

But this time even its mobile fortress could not protect it.

The comet punched through Earth’s atmosphere in fractions of a second. It blasted away the air around it, blowing it into space, leaving a tunnel of vacuum where it had passed.

The ammonite was trapped right under the comet’s fall. It was as if a great glowing lid closed across the sky. Its substance immediately vaporized, the ammonite died. So did the belemnites. So did the elasmosaur. So did the oysters and clams. So did the plankton.

The ammonites had stalked the oceans of the Earth, spawning thousands of species, for more than three hundred million years. Within a year, none of them would be left alive, none. Already, in these first fractions of a second, long biographies were being abruptly terminated.

The few dozen meters of water offered the comet nucleus no more resistance than the air. All the water flashed to steam in a hundredth of a second.

Then the comet nucleus hit the seabed. It massed a thousand billion tons, a flying mountain of ice and dust. It took two seconds to collapse into the seabed rocks, delivering in those seconds the heat energy released by all of the Earth’s volcanoes and earthquakes in a thousand years.

The nucleus was utterly destroyed. The seabed itself was vaporized: rock flashed to mist. A great wave pulsed outward through the bedrock. And a narrow cone of incandescent rock mist fired back along the comet’s incoming trajectory, back through the tunnel in the air dug out in the comet’s last moments. It looked like a vast searchlight beam. Around this central glowing shaft, a much broader spray of pulverized and shattered rock, amounting to hundreds of times the comet’s own mass, was blown out of the widening crater.

In the first few seconds thousands of billions of tons of solid, molten, and vaporized rock were hurled into the sky.

On the coastal plain of the North American inland sea, the duckbill herds gathered around the pools of standing water. They hooted mournfully as they clustered and nudged each other. Predators, from chicken-sized raptors upwards, watched stray duckbill young with cold calculation. In one place a crowd of ankylosaurs had gathered, their dusty armor glistening, like a Roman legion in formation.

An orange glow could be seen deep in the south, like a second dawn. Then a thin, brilliant bar of light arrowed into the sky, straight as a geometrical demonstration— straighter, in fact, than a laser beam, for the beam of incandescent rock suffered no refraction as it pushed out through the hole in the Earth’s superheated air. All of this unfolded in silence, unnoticed.

The crocodile-faced suchomimus stalked the edge of the ocean, her long claws extended. Just as she did every day, she was looking for fish. The death of her mate days before was a dull ache, slowly fading. But life went on; her diffuse grief gave her no respite from hunger.

Elsewhere a group of stegoceras was foraging, scattered. These pachycephalosaurs were about as tall as humans. The males had huge caps of bone on their skulls, there to protect their small brains during their earth-shuddering mating competitions, when they would crash their heads together like mountain sheep. Even now two great males were battling, ramming their reinforced heads together, the bony clatter of their collisions echoing across the plains. This species had sacrificed much evolutionary potential to these contests. The need to maintain such a vast protective cap of bone had limited the development of the pachycephalosaur brain for millions of years. Locked in biochemical logic, these males cared nothing for shifting lights in the sky, or the double shadows that slid across the ground.

On this beach it was just another day in the Cretaceous. Business as usual.

But something was coming from the south.

By now the crater was a glowing bowl of shining, boiling impact melt, wide enough to have engulfed the Los Angeles area from Santa Barbara to Long Beach. And its depth was four times the height of Everest, its lip farther above its floor than the tracks of supersonic planes above Earth’s surface. It was a crater ninety kilometers across and thirty deep formed in minutes. But this tremendous structure was transient. Already great arching faults had opened up, and immense landslides, tens of kilometers wide, began to collapse the steep walls.

And the seabed was flexing. The Earth’s deeper rocks had been pushed down into the mantle by the comet’s hammer blow. Now they rebounded, rising up through twenty kilometers, breaking through the melt pool to the surface. The basement rock itself, almost liquefied, quickly spread out into a vast circular structure, a mountain range forty kilometers across, erected in seconds. Meanwhile water strove to fill the pit that had been dug into the ocean floor. And already ejecta debris was falling back onto the crater’s shifting floor, a rain of burning rock. Temperatures reached thousands of degrees— enough to make the air itself burn, nitrogen combining with oxygen to form poisons that would linger for years to come. It was a chaotic battle of fire, steam, and falling rock.

From the impact site, superheated air fled at interplanetary speeds. A great circular wind gushed out from the Yucatan, down into South America, and across the Gulf of Mexico. The shock wave was still moving at supersonic speeds ten minutes later, when it reached the coast of Texas.