Evolution (7 page)

It didn’t matter. Even if no predator had come this way, her egg would have been destroyed before she could have hatched by a monster even more terrible than a giganotosaur.

Giant was descended from South American stock that had crossed a temporary land bridge into this continent a thousand years earlier.

In a world of slowly separating island continents, the dinosaur fauna had become diverse. In Africa there were archaic-looking long-necked giant herbivores and creatures like hippos with fat, low-slung bodies and powerfully clawed thumbs. In Asia there were small, fast-running horned dinosaurs with noses like parrots’ beaks. And in South America large sauropods were hunted by giant pack-hunting predators; there it was like a throwback to earlier times, to Pangaea. The giganotosaurs had cut their evolutionary teeth hunting the great South American titanosaurs.

Giant was an immature male, and yet he already outmassed all but the very largest carnivores of the era. Giant’s head, in proportion to his body, was larger than a tyrannosaur’s— and yet his brain was smaller. The giganotosaurs were less agile, less fast, less bright; they had more in common with the ancient allosaurs, equipped to kill with teeth and hands, whereas the tyrannosaurs, all their evolutionary energy funneled into their huge heads, specialized in immense, sharklike bites. Where the tyrannosaurs were solitary ambush hunters, the giganotosaurs were pack animals. To bring down a sauropod fifty meters long and weighing a hundred tons, you didn’t need brains as much as raw strength, rudimentary teamwork— and a kind of reckless frenzy.

But, coming across that land bridge into a new country, the giganotosaurs had been forced to confront an established order of predators. The invaders had quickly learned that their takeover of a region could not succeed unless they first mounted a bloody coup against the ruling carnivore.

Which was why this young male giganotosaur was munching slippery tyrannosaur embryos. Resolutely Giant cracked one egg after another. The carefully constructed nest turned into a mess of shattered eggs, scattered moss, and chunks of dismembered chick. Giant was feeding well— and issuing a challenge.

It would be a transfer of power. The tyrannosaur had been the top predator, mistress of the land for a hundred kilometers around, as if the whole elaborate ecosystem was a vast farm run for her benefit. The prey species had come to terms with the formidable presence that lived amongst them: with their armor or weapons or evasive strategies, each of the hunted had reached a point where their losses to predators were not a threat to the endurance of the herd.

Given time, all that would have changed. The impact of the invaders’ hunger would have rippled down the food chain, disturbing creatures large and small, before a new equilibrium could be established. It would have taken longer still for the prey species to learn new behaviors, or even evolve new coping systems or armor to deal with the giganotosaurs.

But none of that would happen. There would not be time for the giganotosaur clan to exploit their triumph. Not in the few hours left.

The nest destroyed, Giant wandered away. He was still hungry, as always.

He could smell putrefaction in the still, misty air. Something huge had died: easy meat, perhaps. He pushed through a bank of tree ferns and emerged into another small clearing. Beyond, through a screen of greenery, he could dimly see the black flank of a young volcanic mountain.

And there, in the middle of the clearing, was a dinosaur— a troodon— standing quite still above a scraping of earth.

Giant froze. The troodon had not seen him. And she was alone; there were none of the watchful companions he associated with the packs of this particular agile little dinosaur.

There was something wrong with the way she was behaving. And that, so the grim predatory calculus of his mind prompted him, gave him an opportunity.

Wounding Tooth should have been able to overcome the loss of a clutch of eggs.

This was a savage time, after all. Infant mortality rates were high; and at any time of life, sudden death was the way of things. This was the world the troodon had been evolved to cope with.

But she could not cope, not anymore.

She had always been the weakest of her brood. She would not even have survived the first days after her hatching if not for the chance decimation of her siblings by a roaming marsupial predator. She had grown to overcome her physical weakness, and had become an effective hunter. But in a dark part of her mind she had always remained the weakest, robbed of food by her siblings, even eyed as a cannibalistic snack.

Add to that a slow poisoning by the fumes and dust of the volcanoes in the west. Add to that an awareness of her own aging. Add to that the hammer blow of her lost brood. She hadn’t been able to get Purga’s scent out of her head.

It had not been hard to pursue that scent out of her home range, across the floodplain to the ocean shore, and now to this new place where the scent of Purga was strong.

Wounding Tooth stood still and silent. The burrow, her nose told her, was right under her feet. She bent and pressed one side of her head against the ground. But she heard nothing. The primates were very still.

So she waited, through the long hours, as the sun rose higher on this last day, as the comet light grew subtly brighter. She did not even flinch when meteors flared overhead.

If she had known about the giganotosaur that watched her she would not have cared. Even if she could have understood the meaning of the comet light, she would not have cared. Let her have Purga; that was all.

It was a peculiar irony that her high intelligence had brought Wounding Tooth to this. She was one of the few dinosaur types smart enough to have gone insane.

It was not yet dark. Purga could tell that from the glint of light at the rough portal to the burrow. But what was day, what was night in these strange times?

After several nights bathed in comet light, she was exhausted, fractious, hungry— and so was her mate, Third, and her two surviving pups. The pups were just about large enough to hunt for themselves now, and therefore dangerous. If there was not enough food, the family, pent up in this burrow, might turn on one another.

The imperatives slid through her mind, and a new decision was reached. She would have to go out, even if the time felt wrong, even if the land was flooded with light. Hesitantly she moved toward the burrow entrance.

Once outside, she stopped to listen. She could hear no earth-shaking footsteps. She stepped forward, muzzle twitching, whiskers exploring.

The light was strong, strange. In the sky cometary matter continued to fall, streaking across the dome of the sky like silent fireworks. It was extraordinary, somehow compelling— too remote to be frightening.

An immense cage plunged out of the sky. She scrabbled back toward the burrow. But those great hands were faster, thick ropy muscles pulling the fingers closed around her.

And now she faced a picket fence of teeth, hundreds of them, a tremendous face, reptilian eyes as big as her head. A giant mouth opened, and Purga smelled meat.

The dinosaur’s face, with its great, thin-skinned snout, had none of the muscular mobility of Purga’s. Wounding Tooth’s head was rigid, expressionless, like a robot’s. But though she could not show it, all of Wounding Tooth’s being was focused on the tiny warm mammal in her grip.

Her limbs pinned against her belly, Purga stopped struggling.

Oddly, Purga, in this ultimate moment, knew a certain peace that Wounding Tooth would have envied. Purga was already in her middle age, already slowing in her movements and thought. And she had, after all, achieved as much as a creature like her could have hoped for. She had produced young. Even encased in the troodon’s cold reptilian grip, she could smell her young on her own fur. In her way she was content. She would die— here and now, in heartbeats— but the species would go on.

But something moved beyond the troodon’s bulky body, something even more massive, a gliding mountain, utterly silent.

The troodon was unbelievably careless. Giant didn’t care why. And he didn’t care about the warm scrap she held in her hands.

His attack was fast, silent, and utterly savage, a single bite to her neck. Wounding Tooth had time for a moment of shock, of unbelievable pain— and then, as whiteness enfolded her, a peculiar relief.

Her hands opened. A ball of fur tumbled through the air.

Before Wounding Tooth’s body fell Giant had renewed his attack. Briskly he slit open the belly cavity and began pulling out entrails. He expelled their contents by shaking them from side to side; bloody, half-digested food showered the area.

Soon his two brothers came racing across the clearing. Giganotosaurs hunted together, but their society was fragile at the best of times. Giant knew he couldn’t defend his kill, but he was determined not to lose it all. Even as he chewed on the liver of Wounding Tooth, he turned to kick and bite.

Purga found herself on the ground. Above her, mountains battled with ferocious savagery. A rain of blood and saliva fell all around her. She had no idea what had happened. She had been ready for death. Now here she was in the dirt, free again.

And the light in the sky grew stranger yet.

The comet nucleus could have passed through the volume of space occupied by Earth in just ten minutes.

In the great boiling it had endured the comet had lost a great deal of mass, but not a catastrophic amount. If it had been able to complete its skim around the sun, it would have soared back out to the cometary cloud, quickly cooling, the lovely coma and tail dispersing into the dark, to resume its aeonic dreaming.

If.

For days, weeks, the great comet had worked its way across the sky— but slowly, its hour-by-hour motion imperceptible to any creature who glanced up at it, uncomprehending. But now the bright-glowing head was

sliding

: sliding down the sky like a setting sun, sinking toward the southern horizon.

All across the daylit side of the planet, silence fell. Around the drying lakes the crowding duckbills looked up. Raptors ceased their stalking and pursuit, just for a moment, their clever brains struggling to interpret this unprecedented spectacle. Birds and pterosaurs flew from their nests and roosting places, already startled by a threat they could not understand, seeking the comfort of the air.

Even the warring giganotosaurs paused in their brutal feeding.

Purga bolted for the darkness of her burrow. The disembodied head of the troodon fell behind her, lodging in the burrow’s entrance, following Purga with a grotesque, empty stare as the light continued to shift.

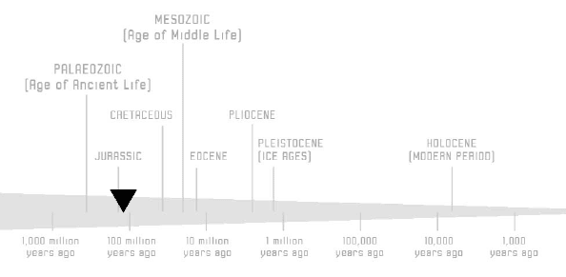

Pangaea. Circa 145 million years before present.

Eighty million years before Purga was born, an ornitholestes stalked through the dense Jurassic forest, hunting diplodocus.

This ornith was an active, carnivorous dinosaur. She was about the height of an adult human, but her lithe body was less than half the weight. She had powerful hind legs, a long, balancing tail, and sharp conical teeth. She was coated in brown, downy feathers, a useful camouflage in the forest fringes where her kind had evolved as hunters of carrion and eggs. She was like a large, sparsely feathered bird.

But her forehead might almost have been human, with a high skullcap that sat incongruously over a sharp, almost crocodilian face. Around her waist was a belt and a coiled whip. In her long, grasping hands she carried a tool, a kind of spear.

And she had a name. It would have translated as something like Listener— for, although she was yet young, it had already become clear that her hearing was exceptional.

Listener was a dinosaur: a big-brained dinosaur who made tools and who had a name.

For all their destructiveness, the great herds of duckbills and armored dinosaurs of Purga’s day were but a memory of the giants of the past. In the Jurassic era had walked the greatest land animals that had ever lived. And they had been stalked by hunters with poison-tipped spears.

Listener and her mate slid silently through the green shade of the forest fringe, moving with an unspoken coordination that made them look like two halves of a single creature. For generations, reaching back to the red-tinged mindlessness of their ancestors, this species of carnivore had hunted in mating pairs, and so they did now.

The forest of this age was dominated by tall araucaria and ginkgoes. In the open spaces there was a ground cover of ground ferns, saplings, and pineapple-shrub cycadeoids. But there were no flowering plants. This was a rather drab, unfinished-looking world, a world of gray-green and brown, a world without color, through which the hunters stalked.

Listener was first to hear the approach of the diplo herd. She felt it as a gentle thrumming in her bones. She immediately dropped to the ground, scraping away ferns and conifer needles, and pressed her head against the compacted soil.

The noise was a deep rumble, like a remote earthquake. These were the deepest voices of the diplos— what Listener thought of as belly-voices, a low-frequency contact rumble that could carry for kilometers. The diplo herd must have abandoned the grove where it had spent the chill night, those long hours of truce when hunters and hunted alike slid into dreamless immobility. It was when the diplos moved that you had a chance to harass the herd, perhaps to pick off a vulnerable youngster or invalid.