Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (41 page)

2.

Antithrombin III deficiency

is present in a mild form in about 1 in 2000 of the population. The thrombotic risk is somewhat unpredictable, but the occurrence of a first thrombotic event in these patients is a relative indication for lifelong anticoagulation therapy with warfarin.

3.

Proteins C and S

are natural anticoagulants. Their deficiency is associated with recurrent venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, but the level of increased risk is less clear than that for the abnormalities above. There is overlap between the serum levels in people with, and apparently without, an increased risk of thrombosis. Testing must occur after at least 2 weeks without warfarin treatment. In homozygotes with protein C deficiency, warfarin may induce skin necrosis.

4.

Prothrombin gene mutation

is present in about 3% of the Australian population. This point mutation leads to an increased plasma level of prothrombin. Its detection requires DNA PCR analysis. It is an autosomal dominant trait and leads to a fourfold increase in the risk of venous thrombosis.

5.

Homocysteine levels

are increased in patients with venous thrombosis and are also an independent risk factor for coronary artery disease. The test is now widely available.

6.

Combined thrombophilic abnormalities

are relatively common and further increase the thrombotic risk.

7.

Antiphospholipid syndrome

is diagnosed if there is clinical evidence of thrombosis or a suggestive history of miscarriage plus an abnormal anti phospholipid antibody test on two occasions.

Anticardiolipin

antibodies and

lupus anticoagulant

(

IgG

or

IgM antiphospholipid

) antibodies are associated with an increased risk of venous thrombus and arterial embolus. In most cases, both are abnormal. The transient presence of these antibodies at low titres is common, is often associated with infection and is probably not of clinical significance. They may be present as part of SLE or occur alone (primary antiphospholipid syndrome).

8.

Consider investigations for other illnesses that are ‘prothrombotic’. These include malignancy, cardiac failure, nephrotic syndrome and haematological conditions such as PNH, polycythaemia rubra vera and thrombocythaemia.

Management

Try to identify transient and continuing risk factors.

1.

In general, an initial episode of thrombosis is treated in the usual way, with low molecular-weight heparin or intravenous non-fractionated heparin. This should be followed by at least 6 months of treatment with warfarin for idiopathic above-knee DVTs or for pulmonary embolism. Patients with antithrombin III deficiency will

still respond to treatment with heparin because of the presence of small amounts of antithrombin III. Tests for the vitamin K-dependent proteins C and S should be performed before the patient is begun on warfarin.

2.

Patients with protein C and S deficiency or heterozygous APC resistance do not need long-term anticoagulation until after their second thrombotic event. Homozygous APC deficiency is an indication for long-term warfarin treatment.

3.

All patients with thrombophilia and their affected asymptomatic relatives need aggressive prophylaxis before surgery or during periods of immobilisation, such as long aeroplane flights. Surgical prophylactic treatment should include heparin, compressive stockings and foot pumps, and early mobilisation. Long aeroplane flights may be an indication for prophylactic subcutaneous fractionated heparin. Aspirin is of proven benefit for the secondary prevention of venous thrombosis.

4.

Pregnant women with a history of DVT require prophylaxis (with heparin) throughout pregnancy and until the puerperium. Warfarin is contraindicated in pregnancy.

5.

The detection of antiphospholipid antibodies in women with miscarriages is an indication for treatment with low-molecular-weight heparin with or without low-dose aspirin during pregnancy. Patients should be advised strongly against smoking and should avoid oestrogen-containing oral contraceptives. Progesterone-only preparations appear to be safe.

6.

There is still controversy about the long-term treatment of patients with antiphospholipid syndrome but recurrent unexpected thrombosis is an indication for long-term anticoagulation with warfarin maintaining an INR between 2 and 3.

Polycythaemia

The myeloproliferative disorders (

Table 8.7

) often occur in the clinical examination. They present a diagnostic and management problem. Polycythaemia rubra vera (erythraemia or increased red cell mass) is the most common myeloproliferative disease encountered. This disease occurs in later middle life and is slightly more common in males. No specific gene defect has been isolated, but the condition is a clonal disease. Secondary causes of polycythaemia (erythrocytosis) must be excluded (

Table 8.8

).

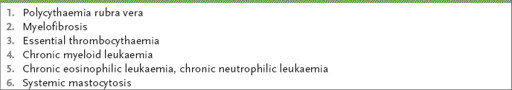

Table 8.7

Myeloproliferative disorders

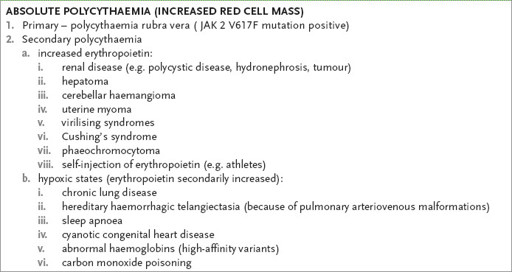

Table 8.8

Causes of polycythaemia

The history

The patient will probably know the diagnosis. If you suspect polycythaemia, ask about:

1.

symptoms of polycythaemia or polycythaemia rubra vera:

a.

vascular problems, such as transient ischaemic episodes, angina, peripheral vascular disease (thrombosis and digital ischaemia); intra-abdominal venous thrombosis, including the Budd-Chiari syndrome

b.

bleeding from the nose

c.

symptoms of peptic ulceration (increased four to five times in polycythaemia rubra vera)

d.

abdominal pain or discomfort from gross splenomegaly or urate stones

e.

pruritus after showering (‘aquagenic pruritis’)

f.

gout

2.

symptoms owing to disease causing secondary polycythaemia (see

Table 8.8

), such as chronic respiratory diseases, sleep disorders and OSA, chronic cardiac or congenital heart diseases, renal diseases (especially polycystic kidneys, hydronephrosis or carcinoma); ask about the use of coal tar derivatives, which can cause the production of abnormal haemoglobin such as methaemoglobin, since secondary polycythaemia may occur as a result

3.

investigations performed and how the diagnosis was made (e.g. blood counts abdominal imaging, and renal, pulmonary and cardiac investigations); the patient may know if the erythropoietin level and JAK 2 kinase mutation has been measured

4.

the treatment initiated (e.g. phlebotomy – how often and for how long, radioactive phosphorus, treatment of renal, pulmonary or cardiac disease)

5.

resolution of symptoms with treatment

6.

social problems related to chronic disease.

The examination

1.

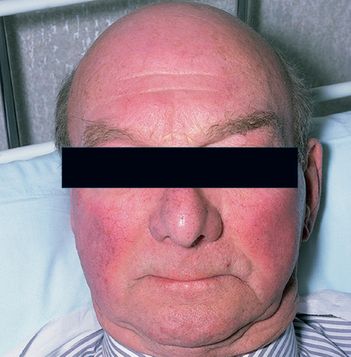

Stand back and look at the patient. Note plethora (see

Fig 8.1

), the state of hydration, cyanosis and any Cushingoid features.

FIGURE 8.1

This face is a diagnostic clue for polycythaemia vera. Patients are frequently plethoric and may have rosacea. M R Howard,

Haematology: An illustrated colour text

, 32, 64–65, Elsevier, 2013, with permission.

2.

Examine the patient’s hands for nicotine stains, clubbing and signs of peripheral vascular disease. Note any gouty tophi.

3.

Look for scratch marks and bruising on the arms and take the blood pressure (systolic hypertension accompanies an increased red cell mass and phaeochromocytoma is associated with increased erythropoietin).

4.

Look at the eyes for injected conjunctivae and examine the fundi for hyper-viscosity changes.

5.

Examine the tongue for central cyanosis.

6.

Examine the cardiovascular system for signs of cyanotic congenital heart disease, if appropriate, and the respiratory system for signs of chronic lung disease.

7.

Examine the abdomen for hepatomegaly (hepatoma must be excluded) and more importantly splenomegaly, which occurs in 80% of cases of polycythaemia rubra vera, but not in secondary polycythaemia. Palpate for renal masses (polycystic kidneys, hydronephrosis, carcinoma). Rarely, uterine fibromas may be found, or very rarely virilisation may be noted.

8.

Look at the legs for scratch marks (pruritus may be secondary to elevated plasma histamine levels), gout and evidence of peripheral vascular disease.

9.

Auscultate over the cerebellar regions for a bruit (cerebellar haemangioblastoma). Note any upper motor neurone signs (cerebrovascular disease owing to thrombosis or the hyperviscosity syndrome).

10.

Check the urine for evidence of renal disease.

Investigations

Confirm the presence of polycythaemia (haematocrit >60% for men or >56% for women) and establish whether this is primary or secondary. Remember that erythrocytosis is an increase in the absolute red cell mass, which occurs as a result of some stimulus (usually hypoxia), and erythraemia (polycythaemia vera) is an increase in red cell mass of unknown aetiology (

Table 8.9

).

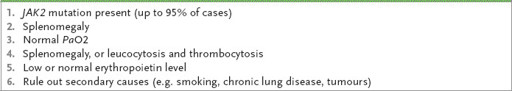

Table 8.9

An approach to the diagnosis of polycythaemia rubra vera

Note:

Red cell mass and plasma volume are no longer routinely measured.

1.

In polycythaemia rubra vera the following are increased: haemoglobin value, haematocrit value, red cell count, white cell count (including the absolute basophil count), platelet count and more variably the neutrophil alkaline phosphatase (NAP) score.

Check the mean corpuscular volume and red cell distribution width (RDW). Microcytic erythrocytosis can only be caused by polycythaemia rubra vera or hypoxic erythrocytosis (RDW usually elevated), or beta-thalassaemia (RDW normal).

2.

The ESR is very low in both primary and secondary polycythaemia.

3.

Assess for splenomegaly (and renal disease) with an abdominal ultrasound or CT scan.