Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (42 page)

Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

4.

Check the arterial blood gases (in polycythaemia rubra vera, 80% of patients have an arterial oxygen saturation >92% and in almost all it is >88%).

5.

Serum erythropoietin level is usually substantially reduced or absent in polycythaemia rubra vera and elevated in secondary polycythaemia. Remember, however, that certain tumours (haemangioblastoma, renal cell carcinoma, renal sarcoma and carcinoma of the liver) cause polycythaemia by excreting erythropoietin.

6.

The total vitamin B

12

level is elevated in 75% of cases of polycythaemia rubra vera. The vitamin B

12

level is raised owing to increased transcobalamin I and III, made by neutrophils, which have an increased turnover.

7.

Rule out renal disease, if indicated.

8.

In polycythaemia rubra vera there is significant panhyperplasia and iron stores are often reduced, but in secondary polycythaemia the bone marrow usually shows an erythroid hyperplasia only. There are no consistent cytogenetic markers. Bone marrow biopsy is not essential for the diagnosis: it is only necessary if another myeloproliferative disorder is suspected. Fibrosis maybe seen in the advanced stages of polycythaemia rubra vera.

9.

Genetic testing is very useful. The

JAK2

mutation is present in most patients with polycythaemia rubra vera.

Treatment

1.

The aim is to lower the haematocrit value to 0.42–0.45 (haemoglobin <140 g/L for men and <120 g/L for women) and maintain it at this level. Patients may die of thrombosis, which seems related entirely to the elevated red cell mass. The presence of thrombocytosis does not increase the risk of thrombotic events, and anticoagulation is not indicated. Thrombotic risk can usually be controlled with phlebotomy alone. Untreated cases have a median survival of 2 years because of the thrombotic risk. This is extended to more than 10 years with phlebotomy alone.

2.

Polycythaemia rubra vera should be treated by phlebotomy. Frequent venesection is required until a state of iron deficiency has been produced. This will then limit red cell production and the frequency may be reduced to about three-monthly.

3.

Radioactive phosphorus (phosphorus-32) irradiates the bone marrow and is easy to use and effective, but it increases the incidence of acute myeloid leukaemia and should be avoided in patients under the age of 70 years (and perhaps in all patients). Alkylating agents (e.g. busulfan) must be monitored closely for the same reason and should not be given routinely. Both P32 and busulfan substantially increase the risk of secondary leukaemia. Hydroxyurea is a much safer drug in these circumstances.

4.

Pruritus may not respond to antihistamines, and interferon alpha (IFNα) or PUVA therapy (combination drugs and ultraviolet light) may be required.

5.

Hyperuricaemia should be treated with allopurinol.

6.

Low-dose aspirin is recommended to prevent thrombosis in patients without excessive gastrointestinal bleeding (avoid high doses).

7.

Secondary polycythaemia is treated by removal of the cause, and phlebotomy if the haematocrit exceeds 0.55.

8.

Interferon alpha may help with the problem of symptomatic splenomegaly.

Idiopathic myelofibrosis

This is a rare form of chronic myeloproliferative clonal disorder. Patients are often asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis. The condition is frequently diagnosed following a routine full blood count or the discovery of splenomegaly. Myelofibrosis may also be the result of a number of malignant and non-malignant conditions (

Table 8.10

).

Table 8.10

Causes of myelofibrosis

Median survival is 4 to 5 years, but patients with severe anaemia (<100 g/L), older age, constitutional symptoms and leucocytosis have a worse prognosis (median survival about 2 years).

Investigations

1.

Occasionally, there may be signs of aggressive extramedullary haematopoiesis: bowel or urethral obstruction, ascites, pericardial effusion, skin masses or spinal cord compression. Rapid splenic enlargement can cause splenic infarction (with the sudden onset of left upper quadrant pain and tenderness). The typical patient is over 50 years of age and has marked splenomegaly (>10 cm) and mild-to-moderate hepatomegaly.

2.

The white cell counts may be normal, increased or decreased. The blood film will show teardrop poikilocytes and a leucoerythroblastic picture (presence of myelocytes, metamyelocytes and nucleated red blood cells). Any process that infiltrates the bone marrow may cause this picture (e.g. malignancy, TB, fungi).

3.

Bone marrow biopsy (aspiration is usually impossible) may reveal karyotypic abnormalities on cytogenetic examination. This finding is associated with a worse prognosis. The JAK 2 V617F mutation is seen in up to 50% of cases.

4.

The condition must be distinguished from myelofibrosis secondary to other conditions, such as lymphoma, leukaemia, myeloma, polycythaemia, chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML) and SLE. These may be amenable to specific treatment.

Treatment

Treatment is primarily supportive. Most patients are treated with repeated blood transfusions.

1.

Hydroxyurea is helpful for symptomatic patients with organomegaly or marked thrombocytosis.

2.

Folate and vitamin B

12

may help if they are deficient; erythropoietin has not been particularly effective. Allopurinol is used when there is hyperuricaemia.

3.

Splenectomy may be indicated if massive splenomegaly has occurred.

4.

Alkylating agents are contraindicated.

5.

Cure is possible only with allogenic bone marrow transplantation for the few patients who are young enough and for whom a suitable donor can be found.

6.

Leukaemic transformation may occur in 10% of patients.

7.

The JAK 2 kinase inhibitor rulxilotinib is effective at ameliorating the natural history and reducing splenic volume.

Essential thrombocythaemia

This is a relatively common form of chronic myeloproliferative clonal disorder. Many patients are asymptomatic and the diagnosis is made on a routine platelet count.

Patients usually present with symptoms related to a high platelet count (>800

3

× 10

9

/L) – especially thromboembolism, but also poor memory, erythromelalgia (painful red extremities) and migraine. Up to 50% of patients have haemorrhagic problems, especially from the gut, and easy bruising. A prolonged bleeding time and abnormal platelet aggregation may be present. An acquired deficiency of von Willebrand factor may occur when platelet numbers are very high; the large von Willebrand multimers are destroyed by the platelets. There are, however, no consistent platelet abnormalities.

Modest splenomegaly (<5 cm) is seen in 50% of patients.

Investigations

1.

A definitive diagnosis requires exclusion of reactive thrombocytosis secondary to infection, polycythaemia, malignancy, inflammation, bleeding, recent surgery or an asplenic state.

2.

Cytogenetic studies may be necessary to exclude CML (Philadelphia chromosome t(9;22) or its products:

BCR-ABL

fusion mRNA or

BCR-ABL

protein).

3.

The

JAK 2

V617F mutation is seen in 50% of cases.

Treatment

1.

Asymptomatic patients, even if they have a platelet count of more than one million, often need no treatment. Unexpectedly, bleeding tends to be more of a problem when the platelet count is over one million and thrombosis when it is less than one million.

2.

Neurological symptoms and erythromelalgia should first be treated with aspirin. Failure of response is an indication to reduce platelet numbers, usually with hydroxyurea or interferon (IFNα). Anagrelide is a more specific antimegakaryocyte agent that can be useful for symptomatic patients, but hydroxyurea and aspirin may be more effective in preventing vascular events.

3.

Bleeding problems may be improved with tranexamic acid; this may be useful if given before surgery.

4.

Transformation to acute leukaemia is uncommon (<10%) and often the result of prior alkylating chemotherapy.

5.

The condition usually runs an indolent and benign course and the continuing temptation to treat asymptomatic patients should be strongly resisted.

Chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML)

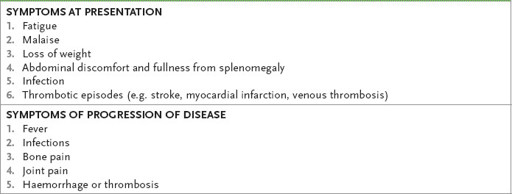

Some patients with CML are diagnosed from routine blood tests – symptoms tend not to be specific (

Table 8.11

).

Table 8.11

CML symptoms

Investigations

1.

The typical patient has moderate splenomegaly (6–8 cm) and a white cell count >50 × 10

9

/L. The white cell differential count will show two peaks, one at the neutrophil stage and the other at the myelocyte stage.

2.

Basophilia and eosinophilia is common.

3.

A low NAP score is another typical laboratory feature. In the blast phase over 20% of white cells are blasts.

4.

Diagnosis depends on finding the Philadelphia (Ph) chromosome (>90%) – a shortened chromosome 22. Translocation of part of chromosome 22 to chromosome 9 results in a hybrid gene

BCR/ABL

rearrangement on chromosome 9.

5.

The platelet count is usually elevated and there is mild normochromic anaemia.

6.

There is no association with alkylating agents and no evidence of a viral cause.

Treatment

Untreated, the disease will eventually undergo blastic transformation.

1.

A cure or long-term remission can be achieved with allogenic bone marrow transplantation from a compatible donor in those who fail to respond or are intolerant of tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy (see below).

2.

Imatinib (a tyrosine kinase inhibitor – TKI) has revolutionised treatment of CML. This drug causes aptosis of cells expressing

BCR

-

ABL.

It is now the first-line treatment for all patients. Its use can be associated with hepatotoxicity, myalgia and fluid retention. The therapeutic target of all TKI treatment is the achievement of a major molecular response, which is defined as a ≥3 log reduction of the baseline quantitative

BCR-ABL

assay, preferably before 12 months from the point of commencing treatment (i.e. ≤0.1%

BCR-ABL

transcript to housekeeping genes is a major response; non-detectable on two samples is a complete response). Some patients will develop mutations in the

BCR-ABL

transcript that confer resistance to imatinib. Second generation TKIs, dasatinib and nilotinib, are available and may be active in these cases.

3.

Interferon alpha therapy is sometimes helpful in the chronic phase. It may induce differentiation of the immature cells and be synergistic with imatnib in achieving a major molecular response.

Lymphomas

These diseases provide complicated diagnostic and management problems. Treatment in expert units is important, because many patients can be cured. Cure should be possible in more than 85% of patients with Hodgkin’s disease and in up to 40% of those with non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas.

Remember that the cell lineage is uncertain for Hodgkin’s disease (although probably mostly B cell), but 80% of non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas are of B cell origin. There are a number of slightly different classification systems. Some are based on the cell type (

Table 8.12

), some are histopathological (

Table 8.13

), and others are clinical staging (

Table 8.14

). The one utilised most in the current academic literature is the WHO (2008) classification.