Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (56 page)

Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

1.

Inspect generally for short stature and obvious deformity (

Fig 10.2

).

FIGURE 10.2

Paget’s disease in an adult. M C Hochberg, A J Silman, J S Smolen et al.,

Rheumatology

, 5th edn. Fig 202.7. Elsevier, 2011, with permission.

2.

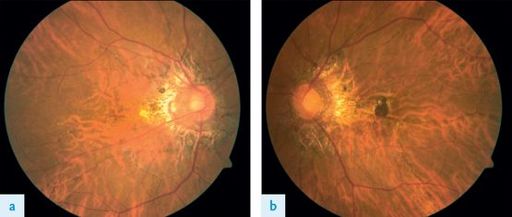

Look at the face. Measure the skull diameter (>55 cm may be abnormal). Look for prominent skull veins, feel for bony warmth (actually caused by vasodilatation in the skin) and auscultate for systolic bruits. Examine the fundi for angioid streaks (

Fig 10.3

), and for papilloedema or optic atrophy, which are rare. Also assess visual acuity and visual fields.

FIGURE 10.3

Angioid streaks in fundus. S J Ryan.

Retina

, 5th edn. Fig 69.1 a and b. Elsevier, 2012, with permission.

3.

Test to see if hearing is decreased as a result of ossicle involvement or eighth nerve compression. Remember,

all

the other cranial nerves may rarely be affected owing to overgrowth of foramina or basilar invagination, so examine them carefully.

4.

Look at the neck for basilar invagination. These patients have a short neck and low hairline, the head is held in extension and neck movements are decreased.

5.

Assess the jugular venous pressure and examine the heart for signs of cardiac failure owing to a hyperdynamic circulation.

6.

Examine the back. Note any deformity, especially kyphosis. Tap for tenderness. Feel for warmth. Auscultate for systolic bruits over the vertebral bodies.

7.

Look at the legs for anterior bowing of the tibia and lateral bowing of the femur. Feel for warmth. Note any changes of osteoarthritis in the hips and knees. There may be limitation of hip movements – especially abduction, which suggests protrusio acetabulae – and fixed flexion deformity of the knees. Be careful, as the bones may be tender.

8.

Sarcomas (a feared, but rare complication) should be looked for, particularly in the femur, humerus and skull; they usually present as tender, localised swellings. They can be multiple.

9.

A full neurological examination is necessary for spinal cord compression and basilar invagination, which may even cause quadriparesis. If the patient is mobile, do not forget to assess walking for any disability. Cerebellar signs may also rarely occur with basilar invagination.

10.

Check the urine analysis (for blood, as renal stone incidence is increased) and measure the patient’s height (for serial follow-up).

Investigations

These are indicated in symptomatic patients requiring treatment and in asymptomatic subjects to determine the extent of skeletal involvement. Paget’s disease is occasionally confused with osteoblastic bone secondaries (e.g. from prostate, Hodgkin’s disease) or fibrous dysplasia.

1.

Testing for hypercalcaemia may be worthwhile for any patient who is immobilised.

2.

The serum alkaline phosphatase level is an indicator of disease activity, as is the urinary hydroxyproline level. Other biochemical markers of bone turnover will also be increased (e.g. osteocalcin, urine or serum cross-links of collagen).

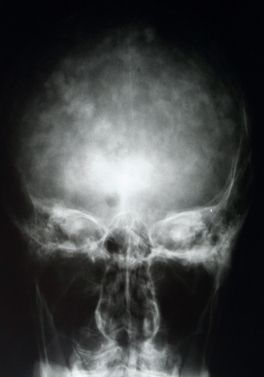

3.

Radiologically the bones most often involved are the pelvis, femur, skull and tibia (see

Figs 10.4

and

10.5

). Look for bony enlargement, increased density, an irregular widened cortex and cortical infractions (incomplete pseudofractures) on the convex side of the bowed long bones. The early lytic phase of the disease, presenting with a flame-shaped osteolytic wedge advancing along the bones, is often overlooked. Secondary arthritic changes may occur (e.g. hips). Bone scanning is more sensitive than an X-ray in assessing the extent of disease. CT scanning or MRI may be useful in the investigation of an atypical lesion, especially if sarcoma is suspected.

FIGURE 10.4

MRI of the lower leg of a patient with Paget’s disease. A large osteosarcoma of the tibia can be seen (arrow). Figure reproduced courtesy of The Canberra Hospital.

FIGURE 10.5

Skull X-ray of a patient with Paget’s disease. Note the bony enlargement of the cranium. Figure reproduced courtesy of The Canberra Hospital.

Treatment

The indications for treatment are bone pain, progressive deformity or complications such as neural compression or high-output cardiac failure, and as a prelude to orthopaedic surgery. Treatment of patients with Pagetic involvement of weight-bearing bones may be indicated to attempt to prevent deformity and pathological fracture. Proof of benefit is not available, however.

1.

Simple analgesics (paracetamol) or NSAIDs, including COX-2 inhibitors, should be used first to control pain. Orthopaedic procedures such as total hip replacement may be indicated.

2.

A number of drugs are available that reduce bone resorption.

a.

An oral bisphosphonate (e.g. alendronate) is usually the first-line treatment. These drugs are effective at reducing hydroxyproline excretion and often relieve symptoms, but may exacerbate bone pain initially. They also impair bone mineralisation and may cause osteomalacia. However, bone turnover is reduced and new bone is usually more normal in structure. The bisphosphonates should be given in combination with calcium supplements and vitamin D. Ulcerating oesophagitis causing dysphagia is an important side-effect. The bisphosphonates are not generally indicated for asymptomatic patients. Intravenous infusions of the potent bisphosphonate pamidronate may produce prolonged suppression of Pagetic activity and may normalise bone turnover in patients with mild disease without adverse effects on bone mineralisation or bone formation.

b.

Calcitonin of salmon or human origin, given subcutaneously, often improves bone pain and may be useful in the treatment of neurological complications. Although side-effects (nausea, flushing and diarrhoea) are common and may limit treatment in up to 20% of patients, it is still regarded as a first-line therapy. Resistance to salmon calcitonin after 1 to 2 years may indicate the development of neutralising antibodies. Serum alkaline phosphatase levels and urinary hydroxyproline levels are useful guides to the effect of treatment; a 50% reduction in either test value indicates a good response to treatment.

c.

Mithramycin, given intravenously, can be very effective. It is reserved for occasions when rapid remission is required (e.g. spinal cord compression). There may be significant increases in bone lysis and predisposition to fractures with this drug, as well as bone marrow depression.

3.

Surgery, including osteotomy for misshapen femurs, may be useful. It is important for the patient to avoid immobilisation in the postoperative period because of the risk of hypercalcaemia.

4.

The appearance of osteosarcoma (see

Fig 10.4

) is associated with a poor prognosis. Preoperative chemotherapy followed by amputation – the current treatment for spontaneously occurring tumours – is being evaluated.

Acromegaly

Although an uncommon condition, three to four new cases per million people a year, acromegaly is a chronic illness and common as a long or a short case.

The history

The patient will probably know the diagnosis, although if the condition has been suspected only recently investigations may still be underway. The patient may be in hospital for these tests because of a complication of the condition or, perhaps more likely, has been brought in for the clinical examinations.

1.

Find out when the diagnosis was made and how long ago; in retrospect, the patient may have had symptoms for years. The average time taken to make the diagnosis is more than 10 years.

2.

Ask why the diagnosis was suspected. The onset of abnormalities is usually very gradual. The common features of the condition are listed in

Table 10.8

. Ask what changes the patient has been aware of and whether these have improved with treatment. Bony and acral changes are irreversible and early diagnosis is worthwhile.

Table 10.8

Symptoms and signs in acromegaly

| Acral enlargement * | Muscle weakness |

| Carpal tunnel syndrome | Paraesthesiae |

| Diabetes mellitus | Peripheral neuropathy |

| Enlarged jaw and facial features * (see Fig 10.6 ) | Skin tags and colon polyps |

| Galactorrhoea | Soft-tissue enlargement * |

| Headache * | Sweating * |

| Impotence and hypogonadism | Symptoms of sleep apnoea |

*

In >50% of patients

3.

Ask about the associations and complications of the condition. The mortality rate for untreated acromegaly is about twice that of the age-matched population, mostly as a result of an increased risk of cardiovascular disease. There is also an increase in the incidence of colonic polyps and carcinoma of the colon.

4.

There is now a recognised association with obstructive sleep apnoea and questions should be asked about snoring, daytime sleepiness and other relevant symptoms. The reason for the association is the enlargement of the tongue and swelling of the upper airway.