Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (67 page)

Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

5.

Ask about general constitutional symptoms. Symptoms of fever, lethargy and weight loss may indicate the AIDS-related complex or suggest an underlying opportunistic infection or malignancy.

6.

Enquire about specific symptoms:

a.

respiratory – cough, dyspnoea, sputum – these may result from

Pneumocystis jirovecii

pneumonia, lymphoid interstitial pneumonitis, tuberculosis, bacterial pneumonia or fungal pneumonia

b.

gastrointestinal – diarrhoea or weight loss as a result of cryptosporidiosis, microsporidiosis, mycobacterial infection or cytomegalovirus (CMV) colitis; odynophagia as a result of oesophageal candidiasis, herpes simplex or CMV ulceration; vomiting and abdominal pain owing to biliary tract disease; drug side-effects (e.g. didanosine-induced pancreatitis) – diarrhoea is usual when patients are treated with protease inhibitors

c.

neurological – meningism caused by cryptococcal meningitis, focal neurological symptoms or seizures as a result of space-occupying lesions, toxoplasmosis or non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma; cognitive decline as a result of HIV dementia or multifocal leucoencephalopathy; peripheral nervous system disease owing to peripheral neuropathy, CMV radiculopathy or myopathy

d.

renal – nephrotic syndrome from HIV-associated nephropathy; renal failure owing to sepsis or drug side-effects

e.

ocular – deteriorating vision, which usually suggests advanced CMV retinitis

f.

dermatological – rashes may be caused by drug reactions, viral infection (e.g. herpes zoster virus (HZV) or herpes simplex virus (HSV)) or fungal infection; itch may be caused by scabies or drug reaction; and nodules can be caused by Kaposi’s sarcoma (

Fig 13.1

) or bacillary angiomatosis. Seborrhoeic dermatitis and psoriasis occur commonly

FIGURE 13.1

Kaposi’s sarcoma on the leg. The lesion is reddish-brown because of its vascular nature and accompanying hemosiderin deposition. J P Piccini, K R Nilsson.

The Osler medical handbook

, 2nd edn. Plate 19. © 2006 The Johns Hopkins University.

g.

mouth – ulcers (aphthous or viral) (

Figs 13.2

and

13.3

), gingivitis, periodontal disease, hairy leucoplakia or candidiasis

FIGURE 13.2

Viral mouth ulcer. Immunocompromised patient with tongue ulcer and fissures secondary to herpes simplex virus. W D James, T Berger, D Elston.

Andrews’ diseases of the skin: Clinical dermatology

, 11th edn. Fig. 19-12. Saunders, Elsevier, 2011, with permission.

FIGURE 13.3

Recurrent intraoral herpes simplex in an adult with numerous, widely scattered vesicles and ulcers in association with pain, tenderness and fever. D W Flint, B H Haughey, V J Lund et al.

Cummings otolaryngology: Head and neck surgery

, 5th edn. Fig 91-32. Mosby, Elsevier, 2010, with permission.

h.

cardiac – dyspnoea, chest pain or palpitations owing to myocarditis or pericarditis

i.

haematological – anaemia (bone marrow suppression or infiltration, treatment with zidovudine); thrombocytopenia and neutropenia are less common.

7.

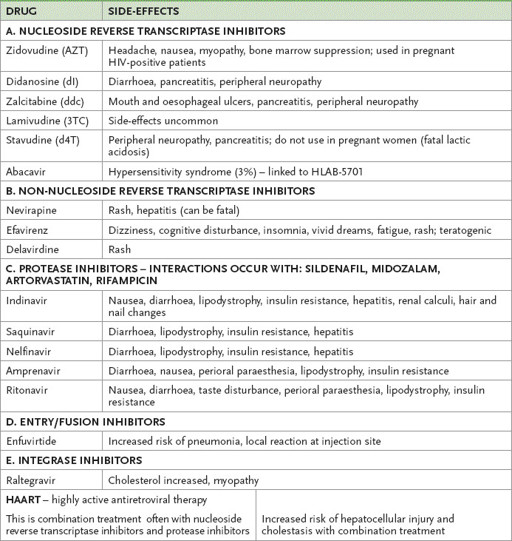

Ask about previous treatment. Find out about antiretroviral drug and antibiotic treatment and about any adverse effects of these. Enquire about specific side-effects (see

Table 13.5

). If the disease has recently been diagnosed, ask what treatment options have been discussed with the patient.

Table 13.5

Side-effects of selected antiretroviral drugs

8.

Ask about previous investigations. The patient may be able to give much helpful information on previous investigations, including viral load results, T cell CD4

+

counts, MRI scans, CT scans, lumbar punctures, bone marrow biopsies and endoscopy.

9.

Enquire about social, drug and alcohol history. The examiners will expect quite detailed knowledge of the patient’s social, economic and family circumstances.

10.

Ask about risk factors and treatment for cardiovascular disease.

The examination

Note especially:

1.

temperature

2.

nutritional state (wasting is common in advanced disease); there may be fat loss on the face and fat gain over the limbs (retroviral drug effect)

3.

skin (e.g. rashes – seborrhoeic dermatitis (

Fig 13.4

), molluscum contagiosum – pigmentation and the lesions of Kaposi’s sarcoma)

FIGURE 13.4

The hands of a patient with psoriatic arthritis and HIV infection. M C Hochberg, A J Silman, J S Smolen et al.

Rheumatology

, 5th edn. Fig 107.1. Mosby, Elsevier, 2010, with permission.

4.

mouth (e.g. hairy leucoplakia, Kaposi’s sarcoma lesions, periodontal disease, HSV mouth ulcers)

5.

eyes – acuity, visual fields and fundoscopy (e.g. CMV retinal lesions)

6.

cognition, gait and coordination (e.g. AIDS dementia)

7.

chest – cough, sputum, crackles (e.g. opportunistic chest infection)

8.

heart – cardiac failure, pericardial disease (e.g. AIDS cardiomyopathy)

9.

abdomen – rectal examination, perianal disease (especially warts and HSV)

10.

haematological system – lymph nodes and spleen.

Investigations

The patient is likely to have had many tests.

1.

The standard screening test for HIV is an ELISA or enzyme immunoassay (EIA) test. It tests against antigens of both HIV1 and HIV2 (very rare in Australia). It has a sensitivity of more than 99%. Its specificity in low-risk populations is only about 90%. False positives can occur related to recent vaccinations, other viral infections and autoimmune diseases. The earliest detectable test is an HIV PCR DNA (within a few days of inoculation).

2.

The western blot test is more specific and a negative western blot means a positive EIA test is a false positive.

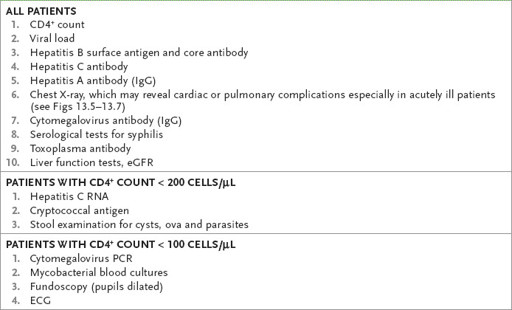

3.

Other tests are used to assess the severity of the illness and immunocompromisation, and to look for associated conditions (e.g. syphilis) and complications. The currently relevant tests will depend on the clinical presentation; however, certain tests are essential for all patients, either as a baseline or for monitoring (see

Table 13.6

).

Table 13.6

Routine initial investigations for HIV patients

BASELINE

1.

Immune function needs to be established at this point with a full blood count, CD4

+

level (levels >200 cells/μL are associated with opportunistic infections) and HIV plasma serum viral load.

2.

A delayed-type hypersensitivity skin test will help define cellular immune function. The lower the CD4

+

(T helper cell) level (

Table 13.7

) and the higher the HIV viral load, the more advanced the infection. CD4

+

levels may fall progressively to undetectable levels. Aggressive treatment of infections may allow continued survival of patients despite these low CD4

+

levels. Antiviral treatment may slow CD4

+

depletion or stabilise it for many years. About 5% of infected patients do not develop a reduction in CD4

+

counts even after more than 10 years without treatment. These patients are called ‘non-progressors’.

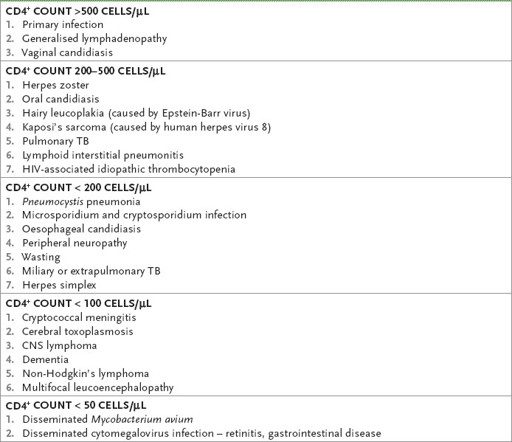

Table 13.7

CD4

+

level and common clinical features