Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (65 page)

5.

Vertigo is the illusion of movement of the self or the environment. The sensation may be rotational. Often nausea, vomiting, imbalance and anxiety are associated.

a.

Causes of this condition include vestibular neuronitis, acute labyrinthitis, benign positional vertigo, Ménière’s disease, vertebrobasilar insufficiency, posterior fossa neoplasms, cerebellar haemorrhage and MS.

b.

Cerebellar haemorrhage characteristically causes severe associated nausea and vomiting, and is of sudden onset.

c.

Ask whether the vertigo is related to the position of the head (e.g. made worse by turning over in bed or by looking up). This symptom suggests labyrinthine disease, most commonly benign positioning vertigo.

6.

Unsteadiness of gait may be secondary to a number of disorders of the peripheral or central nervous system. Drug side-effects, neoplasms, cerebellar and extrapyramidal diseases can present in this way.

7.

Hypoglycaemia is an important, albeit rare, cause of funny turns and must always be considered in the differential diagnosis of suspected cerebrovascular disease. It is associated with hunger, sweating, tremor and tachycardia (owing to catecholamine release), as well as neurological dysfunction. Causes of hypoglycaemia include: too much insulin or oral hypoglycaemic agent and not enough food; reactive or postprandial, usually among patients with gastric surgery; or fasting (especially among patients with hypopituitarism, adrenal insufficiency, cirrhosis, alcoholism or rarely an insulinoma).

8.

There are a number of cardiac causes of funny turns or syncope.

a.

A dizzy feeling related to standing up and without any component of true vertigo suggests postural hypotension. This can be a complication of antihypertensive treatment, especially with vasodilating drugs, and occasionally occurs in patients with single-chamber ventricular pacemakers (pacemaker syndrome).

b.

Orthostatic hypotension is common in the elderly and in patients with autonomic neuropathy (e.g. secondary to diabetes mellitus).

c.

Episodes of complete heart block may complicate ischaemic heart disease or be caused by degenerative disease of the conducting system. These patients describe syncope occurring without warning. Unless they have been injured by the fall they feel normal again immediately.

d.

Ventricular and supraventricular tachyarrhythmias may cause dizziness or syncope, possibly associated with palpitations. Ventricular arrhythmias are more likely in patients with known structural heart disease (e.g. previous infarction). Remember that antiarrhythmic drugs can cause bradycardia and are associated in some cases with dangerous proarrhythmic effects.

e.

Patients with severe aortic stenosis may present with exertional syncope, which is usually associated with ischaemic-like chest pain.

9.

Other conditions that need to be considered include episodes of hyperventilation or panic attacks. Patients who sigh often because of anxiety are rarely aware of any abnormality of their breathing. Their dizziness is often accompanied by a sensation of swaying. Transient global amnesia sometimes presents as a funny turn involving temporary disorientation and loss of memory.

10.

Find out about risk factors and associated symptoms.

a.

If a TIA or stroke is suspected, enquire about risk factors for vascular disease (in particular, smoking, hypertension, diabetes and hyperlipidaemia).

b.

Neck pain may indicate arterial dissection.

c.

Symptoms of connective tissue disease or thrombotic episodes may be relevant.

d.

Ask for a list of all the drugs the patient has been taking. Enquire about medications that increase the risk of vascular episodes, including oral contraceptives and some peripheral vasodilator drugs that can lower blood pressure. Also ask specifically about sedatives, hypoglycaemic agents, anticonvulsants and drugs affecting cardiac conduction.

The examination

A complete examination of the neurological and cardiovascular systems is essential, but must be guided by the symptoms.

1.

The fundi should be carefully examined for evidence of emboli, hypertensive changes, diabetic changes and ischaemic retinopathy. Test the visual fields (e.g. left or right half visual field loss in a carotid territory stroke). Look for nystagmus.

2.

Carotid bruits should be listened for, but their absence does not exclude tight carotid stenosis. Unfortunately, even if a bruit is present, this does not necessarily indicate tight common or internal carotid artery stenosis, because external carotid artery stenosis can also cause a bruit.

3.

If indicated, perform the Hallpike test for benign paroxysmal positional (positioning) vertigo (BPPV).

4.

Check all the pulses. Decide whether atrial fibrillation is present. Test the blood pressure lying and standing for postural hypotension. Listen for murmurs (e.g. as a result of aortic stenosis, infective endocarditis, rheumatic heart disease or a prosthetic valve). Examine for peripheral vascular disease. Note the presence of an electronic pacemaker.

5.

Palpate over the temporal areas for the tenderness of giant cell arteritis.

Investigations

1.

In patients with a suspected, but not typical, TIA it is worthwhile checking a full blood count, ESR (elevated in temporal arteritis and in connective tissue disease), fasting plasma glucose (for evidence of diabetes or hypoglycaemia), cholesterol (for hypercholesterolaemia), urinalysis (for evidence of renovascular disease) and an ECG (for evidence of ischaemic heart disease, arrhythmia or heart block). Look for a long or short QT interval. Patients in sinus rhythm, but with bifascicular or trifascicular block, may be having episodes of complete heart block. Serological testing for tertiary syphilis (

Treponema pallidum

haemoglutination test (TPHA)) is rarely indicated.

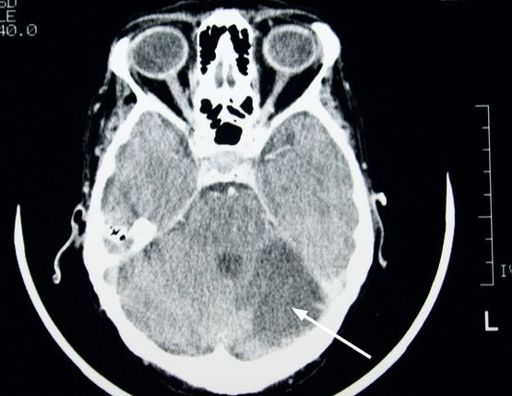

2.

A CT or MRI scan of the head (see

Figs 12.3

and

12.4

) should be performed for all patients with a TIA or stroke, as 5% of TIAs are caused by structural lesions. A CT scan is also worth performing in patients with established stroke to exclude haemorrhage, as this may alter management.

FIGURE 12.3

MRI of the brain showing a metastatic cerebellar tumour (arrow). Figure reproduced courtesy of The Canberra Hospital.

FIGURE 12.4

MRI of the brain showing a cerebellar infarct (arrow). Figure reproduced courtesy of The Canberra Hospital.

3.

A carotid ultrasound should be performed in patients who have carotid territory TIAs. Suggestive features of a carotid artery TIA include monocular visual loss, unilateral sensory disturbances or weakness, or aphasia. Vertebrobasilar TIAs, on the other hand, may cause bilateral visual loss, weakness or sensory disturbance, and crossed sensory and motor loss. If a greater than 70% stenosis of the origin of the internal carotid artery on the symptomatic side is found, carotid angiography should be considered with a view to endarterectomy or angioplasty, which is of value in otherwise fit patients.

4.

Transoesophageal echocardiogram (TOE) should be considered in any stroke patient with abnormalities on examination of the heart or with abnormalities on the ECG (or chest X-ray). It is also recommended when no other cause has been found for the episode. A TOE with contrast injection may reveal a patent foramen ovale. This known cause of paradoxical embolism is present in up to 30% of people. Trials are underway to establish the benefits (if any) of catheter-based closure of these when they are detected in patients with otherwise unexplained stroke, but remember that stroke is an uncommon cause of syncope.

5.

Patients with atrial fibrillation should have their thyroid function checked and an echocardiogram performed to look at left ventricular size – a predictor of risk of embolic events. Rarely an intracardiac mass (usually a left atrial myxoma) is discovered.

It is a rare cause of stroke and is often associated with systemic symptoms. Resection is usually possible.

6.

In relatively young patients with a TIA (<50 years of age), careful attention to the possibility of a connective tissue disease is worthwhile. Check an antinuclear antibody, anticardiolipin antibody (because of antiphospholipid antibody syndrome) and procoagulation profile.

Management

This will, of course, depend on the diagnosis in the particular case. If a TIA is likely, you should plan to discuss vascular risk factor treatments, anti-platelet therapy and the role of carotid endarterectomy.

1.

There is a direct relationship between high blood pressure, smoking and cholesterol level and an increased risk of ischaemic stroke as well as coronary artery disease. Therefore, management of risk factors by conservative means or with drugs is essential.

2.

Anti-platelet therapy reduces the risk of stroke in patients prone to TIAs. Low-dose aspirin (between 75 and 100 mg per day) is a reasonable regimen to use. Clopidogrel is an adenosine diphosphate (ADP) inhibitor and an expensive alternative to aspirin. Recurrence of symptoms when patients are already taking aspirin is an indication for

the combination of aspirin and dipyridamole. Aspirin and clopidogrel in combination have not been shown to be more effective than aspirin alone. At least 2 years of treatment is necessary after a TIA, but many would recommend the lifelong use of anti-platelet agents.

In those with atrial fibrillation not caused by rheumatic heart disease, aspirin reduces the risk of a recurrent event by one-fifth and warfarin reduces it by one-half. The risk of major haemorrhage with warfarin use is less than 2% per year, especially if the INR is kept below 2.5. Most cardiologists would recommend warfarin or anticoagulation with one of the newer direct thrombin inhibitors or anti-Xa drugs, to any patient in atrial fibrillation who has had a definite or even a possible embolic event and in patients with an elevated CHADS score (

p. 79

). In those who have rheumatic heart disease, mechanical prosthetic heart valves or other cardiac sources of emboli, long-term anticoagulation with warfarin is strongly recommended.

3.

Carotid endarterectomy or angioplasty is worth considering in patients with a TIA in the carotid territory within the preceding 6 months who have documented severe (>70%) stenosis of the origin of the internal carotid artery on the symptomatic side. Surgery in such cases is definitely superior to medical therapy. A decision to operate should be based on the availability of surgical expertise and the complication (stroke) rate of a particular surgical unit.

4.

Other treatment will depend on the final diagnosis and can range from anticonvulsants to pacemaker insertion. It is usually unwise to treat these patients without an established diagnosis.

CHAPTER 13

The infectious disease long case

Humanity has but three great enemies: fever, famine and war; and of these by far the greatest, by far the most terrible, is fever.

Harvey Cushing (1869–1939)

Pyrexia of unknown origin

Although not a common long case, pyrexia of unknown origin (PUO) presents both diagnostic and management problems. The term ‘pyrexia of unknown origin’ is used only for patients with a fever >38.3°C for more than 3 weeks, for whom no diagnosis has been made during a week of intensive study. The common causes of PUO are listed in

Table 13.1

.

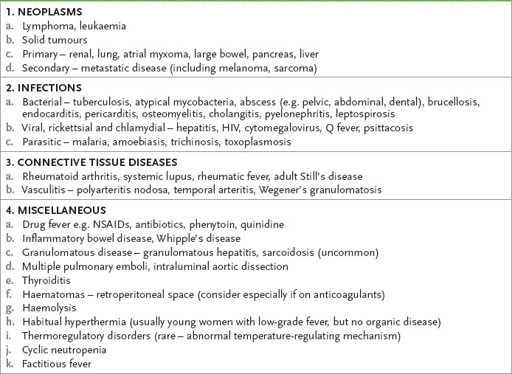

Table 13.1

Important causes of pyrexia of unknown origin