Execution: A Guide to the Ultimate Penalty (22 page)

This slow and cumbersome system was soon superseded by a mass-production or, perhaps one should say, a mass-extermination method, in which the unfortunates, on arrival at a concentration camp, would be informed of the need to shower before being issued with clean clothes and allocated to huts.

Having undressed, they were then herded into the long sanitary-looking rooms, any suspicions being lulled by the spray-heads set in the ceilings. But instead of clean hot water, Zyklon B, prussic acid manufactured by the chemical company I. G. Farben, was sprayed on the packed mass of humanity through the vents above them.

By this means 1,000 victims could be disposed of, albeit agonisingly, in 30 minutes, some death camps achieving a killing rate of 5,000 per day, inevitable delays being caused by the need to vent the ‘shower-rooms’ and empty them of their macabre contents. This was done by hosing the blood and excrement from the heaps of contorted bodies, then dragging them out using long hooked poles. Once stacked on the adjacent conveyor belts, the remains were transported to the camp crematorium to be burned, the ashes subsequently being used for fertiliser.

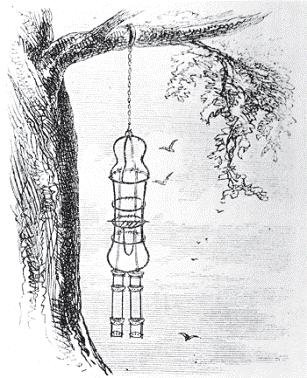

GIBBET

‘Round the knees, hips and waist, under the arms and around the neck of the naked victim, iron hoops were riveted close about the different parts of the body.’

Although the word gibbet was sometimes used as another name for the gallows, it more accurately refers to a close-fitting iron cage in which the dead bodies of hanged men were displayed at crossroads and hilltops as a deterrent to would-be wrong-doers. Cases did occur, however, where confinement in a gibbet was itself the sentence which ultimately brought death, mainly from exposure and starvation.

This was the fate suffered by Andrew Mills, a farm servant who, on 28 January 1683, murdered his master’s three children, John, Jane and Elizabeth Brass. The parents were away from home, and the two youngest children were asleep in an inner room when Mills broke into the house. The eldest, a daughter, had her arm broken when she used it as a bolt across the door to bar his entry into the room, and was the first to be killed, the other children being murdered soon after.

Captured by troopers some time later, he was tried at Durham. Despite his obvious mental instability – during his confession he insisted that the devil had urged him on, saying, ‘Kill all, kill all’ – he was condemned to be gibbeted near the scene of the crime. It was asserted that he survived for several days, his sweetheart keeping him alive with milk. Another source, however, tells how a loaf of bread was placed just within his reach, but fixed on an iron spike that would pierce his throat if he attempted to alleviate his hunger. His cries of pain were terrible and reportedly could be heard for miles around, causing local families to leave their homes until after his death.

A murderer who was certainly responsible for his actions was highwayman John Whitfield who, in 1777, was gibbeted alive on Barrock Hill, near Wetherall, Carlisle. He had been seen shooting a traveller and, once identified, was convicted and suspended in the gibbet. There he swung for several days, his cries for mercy being so heart-rending that the driver of a passing mail coach put him out of his misery by shooting him!

In the West Indies many criminals were sentenced to the gibbet. Two murderers were gibbeted alive in Kingston, Jamaica, crowds gathering to abuse them, and Balla, the leader of a rebellion in 1788, was suspended in a gibbet in Dominica and survived for a week before expiring. In 1759 a slave suffered the same penalty at St Eustatia, managing to cling on to life for an incredible 13 days, constantly begging for water before eventually succumbing. Lest it should be thought that the gibbet was little more than a cage designed solely to cast shame and opprobrium on its occupant, in the same way as did the stocks and the pillory, a description in the periodical

Once a Week

dated 26 May 1866 revealed the harsh reality of the device:

‘Round the knees, hips and waist, under the arms and around the neck of the naked victim, iron hoops were riveted close about the different parts of the body. Iron braces crossed these again, from the hips right over the centre of the head. Iron plates and bars encircled and supported the legs, and at the lower extremities were fixed plates of iron like old-fashioned stirrups in which the feet might have found rest, were not the torture increased, compared to which crucifixion itself must have been mild, by the fixing of three sharp pointed spikes in each stirrup, to pierce the soles of the victim’s feet.

The only support the body could receive, while strength remained or life endured, was given by a narrow hoop passing from one end of the waist bar in front, between the legs, then to the bar at the back. Attached to the circular bar under the arms, stood out a pair of handcuffs, which prevented the slightest movement in the hands, and on the crossing of the hoops over the head was a strong hook, by which the whole fabric, with the sufferer enclosed, was suspended.’

And so, his hands secured, unable to rest his feet on the stirrups, his whole weight taken by the bar between his legs, deprived of food and water, exposed to the tropical sun, death came not violently by rope or gunshot, but slowly and agonisingly over many days.

Nor were men the only ones to suffer in the gibbet. The same periodical went on to report that a cage was at that time, 1866, on display in the Museum of the Society of Arts in Kingston, Jamaica, adding that when the device was found it contained the bleached skeleton of a woman.

Jamaica irons

GRIDIRON

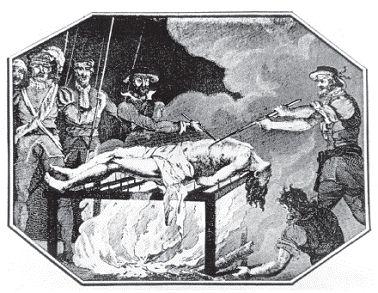

‘[H]e was brought before him and hung up and beaten for a very long time with scourges, then rubbed with vinegar and salt, and finally broiled on a gridiron over a slow fire.’

When it came to executing Christian martyrs and the like, there were many items listed in the executioners’ menu capable of appealing to the tastes of their masters: the victims could be fried in oil, resin or sulphur, boiled in water or oil, roasted in ovens or, arguably the most painful, broiled on a gridiron.

As described in the ancient records, the contraption ‘was framed of three iron bars set lengthwise and a span distant from each other, one finger thick, two broad, and of a length suitable for its purpose, with seven or more shorter pieces of iron placed crosswise, and likewise separated a span from each other. Of these, some were round, some square, the square ones being the two which joined the ends of the longitudinal bars, to brace together and strengthen the whole structure. There were also fixed at each corner, and in the middle, supports, raising the framework a little off the ground, and serving as legs.’ In more modern terminology, a barbecue designed to cater for a martyr rather than the more usual picnic repasts.

Many suffered broiling while being held down with long iron forks, among them being Sts Dulas, Eleutherius, Conon, Dorotheus, Macedonius, Theodolus, Tatian and Peter. The latter, chamberlain to the Emperor Diocletian, was indiscreet enough to deplore the harshness of the tortures then being administered to those of the Christian faith. And so, by his master’s orders ‘he was brought before him and hung up and beaten for a very long time with scourges, then rubbed with vinegar and salt, and finally broiled on a gridiron over a slow fire’.

Another whose suffering is commemorated to this very day by a magnificent group of buildings near Madrid is St Lawrence. A man with a well-developed sense of humour, which alas, proved to be his downfall, he was a deacon in Rome; ordered to produce the treasures of his church so that the authorities could confiscate them, he promptly marshalled the beggars in his care! Such facetious behaviour was not to be tolerated, and, in

ad

258, he was sentenced to be broiled to death.

Secured to the gridiron, the stoking of the fire beneath it only served to sharpen his wit for, as the hours went by, he exclaimed to the executioner and officials surrounding him: ‘This side is roasted enough, oh tyrant great; decide whether roasted or raw thou thinkest the better meat!’

The tenth of August is St Lawrence’s Day, the date on which, in 1557, King Philip II of Spain decisively beat the French at San Quentin. Attributing his victory to the saint whose day it was, in grateful thanks he built the Escorial, a complex of buildings some little distance from Madrid, which incorporated a Royal palace, college, monastery and a mausoleum.

The Escorial took 24 years to complete, the general design featuring St Lawrence’s symbol throughout. The ground plan faithfully reflected the gridiron, the buildings being the cross-bars, and the palace the handle. Gridirons of wood and plaster, metal and pigment decorate the rooms and corridors, the halls and the galleries, while a silver statue of the saint, bearing a gridiron in his hands, greeted visitors to the great complex. Never was an instrument of martyrdom so multiplied, so honoured, so celebrated, as that on which St Lawrence met his agonising death.

Broiling can take place just as easily without a gridiron, of course, but one would hardly think that such a torture could take place in the present century. Nevertheless, it was practised by the Cheka, latterly known as the KGB, during the Russian Revolution, when officers on the steamer

Sinope

, moored in the harbour at Odessa, were suspended from beams in the engine-room in front of the ship’s furnaces and slowly broiled.

St Lawrence tortured on a gridiron over a fire