Execution: A Guide to the Ultimate Penalty (26 page)

‘Among those executed on 14 April in Bruges was Isabeau Herman, a young girl twenty-two years old, whose beauty, youth and misfortune had attracted the sympathy of the onlookers, for on mounting the scaffold she had flung herself on her knees and begged the pardon of the crowd for the scandal she had caused by her irregular life.

When the moment of her execution had come, the executioner, a very old man named Bongard, had failed to tie her legs to the bascule, and had left on her head her bonnet, in which her hair was gathered up. He had also omitted to cut her hair, and the movements of her head had caused some of her locks to fall on to the back of her neck.

When the blade fell, it did not sever her head, which remained full of life. She was horribly convulsed, and her legs fell off the board, leaving her in an indecent position. The executioner raised the blade a second time, but it proved unable to detach her head until finally, at a third stroke, it was severed from her body. A howling mob besieged the scaffold; on every side cries arose that the executioner must be stoned, and his life was only saved by the intervention of the armed police surrounding the scaffold.’

Among other necessary precautions, it was essential that the guillotine be aligned on an even keel; any diversion from the horizontal would cause the blade to jam in its grooves during the descent, as occurred when a M. Chalier was to be dispatched. Instead of descending at an ever-increasing speed, the blade slid slower and slower, only to make merely a superficial wound in the victim’s neck. Three further attempts achieved little more than to deepen the wound, until at last the desperate executioner, named Ripert, by now the target of heated abuse and jeers from the horrified crowd, resorted to using his knife to decapitate the now badly mutilated victim. Worse was to follow, for Chalier was bald and so Ripert had to display the head to the crowd by holding it by the ears.

Baldness among the victims was always a problem, for in order to stretch the victim’s neck ready for the blade the assistant executioner had then to pull on the ears instead of the hair. One man, Lacoste by name, had but small ears, and, even though he was held down by the lunette, managed to twist his head sharply and sink his teeth into the assistant’s hand just as the blade hissed down. The head fell, the jet of blood, as usual, spurting all over the assistant, who looked down into the basket to see the end of his severed thumb gripped firmly between the teeth of the grimacing head.

So efficient maintenance of the guillotine was highly essential, especially with respect to the grooves: any obstruction due to dirt or corrosion would interrupt the execution and increase the hysteria already mounting within the victim on the bascule and the others waiting in the queue at the foot of the scaffold. This was probably the cause in a case described by Victor Hugo in his work

The Last Days of a Condemned

:

‘The man was confessed, bound, his hair cut off; placed in the fatal cart, he was taken to the place of the execution. There the executioner took him from the Priest, laid him down and bound him to the guillotine, then let loose the axe. The heavy triangle of iron slowly detached itself, falling by jerks down the grooves, until, horrible to relate, it wounded the man without killing him! The poor creature uttered a frightful cry. The disconcerted executioner hauled up the axe and let it slide down again. A second time the neck of the malefactor was wounded without being severed. The executioner raised the axe a third time, but no better effect attended the third stroke.

Let me abridge these fearful details. Five times the axe was raised and let fall, and after the fifth stroke the condemned was still shrieking for mercy. The indignant populace commenced throwing missiles at the executioner, who hid himself beneath the guillotine, and crept away behind the gendarmes’ horses; but I have not yet finished, for the hapless culprit, seeing he was left alone on the scaffold, raised himself on the plank, and there standing, frightful, streaming with blood, demanded with feeble cries that someone would unbind him!

The populace, full of pity, were on the point of forcing the gendarmes to help the hapless wretch, who had five times undergone his sentence. At this moment the servant of the executioner, a youth under twenty, mounted on the scaffold and told the sufferer to turn round, that he might unbind him; then, taking advantage of the posture of the dying man who had yielded himself without any mistrust, sprang on him, and slowly cut through the neck with a knife! All this happened; all this was seen!’

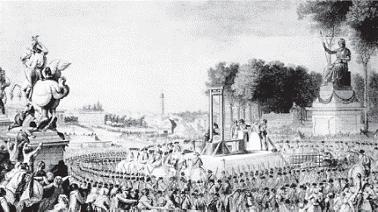

The execution of Marie Antoinette

A similar instance occurred on 8 February 1836. Would-be assassins Lacenaire and his fellow conspirator Avril had attempted to kill King Louis-Philippe, using a multi-barrelled type of rifle. The weapon malfunctioned, and, although the king escaped injury, 18 bystanders were killed and many more wounded. The conspirators were sentenced to death, but Lacenaire suffered indescribable horrors as, face down on the guillotine, he heard the swish of the descending blade, felt the accompanying judder vibrating through the structure – then sudden, horrifying silence as the blade suddenly stopped inches above his neck! Galvanised into action, the executioner, Henri-Clement Sanson, raised the blade twice more before the defect was rectified and the execution finally carried out.

Henri, the last of that dynasty of decapitators, ended his career in disgrace. Far from being dedicated to his profession, he turned for distraction to drink and the gambling-tables of Paris, frittering away the family wealth by his debauchery. Getting deeper and deeper into debt, he was confined in the debtors’ prison in March 1847, regaining his freedom only by pledging his sole valuable possession to his debtors – the guillotine itself.

During the next few weeks he must have dreaded a call from the authorities demanding his services – together with the necessary equipment. Sure enough, the summons came. All his pleas to his debtors for the return of the vital machine, if only for the one day, were rejected. Abjectly, the guillotine-less executioner had to report to the public prosecutor, there to explain the reason for the discrepancy in the inventory. Regrettably, history has drawn a discreet veil over the conversation that ensued. Suffice it to say that the authorities had to produce the four thousand francs or so in order to redeem the machine – and Henri was informed that his services would no longer be required.

Unluckily for a Mme Thomas, the guillotine was available and waiting for her when on 23 January 1887 she mounted the scaffold watched by a large crowd which included many journalists from Paris, a 100 miles away. In a vain attempt to thwart justice, she used her feminine wiles by starting to take off her clothes.

Restrained from such an outrageous performance, Mme Thomas was dragged by the assistant executioner by her hair to the bascule, then held down in the lunette by her ears. The executioner, Louis Deibler, Monsieur de Paris, was so upset by this experience that he tendered his resignation, saying that never again would he execute a woman, even if this cost him his lucrative job.

His resignation was not accepted nor was necessary, for since then the death sentence passed on women was always with the understanding that it would not be carried out (except for a brief reversion during the Second World War).

Until Napoleon III reduced the government’s expenses by appointing one national executioner, each province had its own headsman. Louis Deibler had been Monsieur de Rennes, executioner for Brittany, his appearance on the scaffold enhanced by his habit of wearing a top hat. As was the custom, he married another executioner’s daughter, a lady by the name of Zoe, her father being Rasseneux, Monsieur d’Alger.

Upon his retirement in 1899, his 36-year-old son Anatole succeeded him as the national executioner. This new Monsieur de Paris, the last to bear the family name, which was of Bavarian origin and had provided France with headsmen for over 110 years, was a tall, bearded and quietly spoken man who carried out his duties with great expertise; he officiated at 400 executions during his reign. His hobbies were fishing and sprint cycling, and it was while attending a meeting of the Auteuil Velocipedic Society that he met the girl who was to become his wife. Mme Deibler’s family was related to an even older clan of executioners, the Desfourneaux, one of whom, Henri, was valet (as executioner’s assistants were called) to Anatole Deibler. In later years Henri had ambitions to marry their daughter, but Mme Deibler demurred, saying that she’d rather see the girl dead than married to an executioner.

During Anatole’s term of office, even as recently as the 1930s, the guillotine was still regarded as the executioner’s property and stored in a suburban barn until required. Assembled on the morning of the execution by the assistants with the aid of spirit levels, it was then tested using a bundle of straw.

At the prison, the condemned man was never told in advance of the day of his execution. Instead, he was awakened with the phrase ‘Have courage’ and given a cigarette and a drink of rum. Transported in a horse-drawn, lantern-lit tumbril, he was saluted with drawn sabres by the Garde on his arrival at the scaffold. The executioner, who would perhaps still be adhering to the tradition of wearing a red flower in his buttonhole – in earlier days it was worn behind one ear, as a bloody token of his calling – would address him as ‘thou’, the ultimate term of friendship.

Early in 1939, still in harness after 40 years as France’s executioner, Anatole died, suffering a heart attack in a Metro station while on his way to his 401st guillotining. He always averred that he couldn’t afford to retire, as the job carried no pension! In 1991 his diaries were auctioned in Paris for £66,000; as meticulous as he had been when despatching his many victims, his diaries included not only the names of his victims and the dates of their executions, but also their crimes – and the weather at the time!

His only son having been accidentally killed as a child, by taking a poisonous prescription made up by a careless chemist’s clerk, Anatole left no male heir, and the post of executioner passed to Henri Desfourneaux. Having been Anatole’s valet for many years, he took over without the need for any additional training. Fame of a kind awaited him, for he was to have the doubtful distinction, only months later, of performing the last public execution in France, when he guillotined murderer Eugen Weidmann.

The condemned man, a German born in 1908, had had a life of crime, resulting in prison sentences for armed robbery and assault. In 1937 he resorted to kidnapping for ransom, and abducted an American dancing instructor, Jean de Koven. His plan misfired and he murdered his victim, burying her body beneath the steps of a villa in La Voulze, where it remained undiscovered for over four months.

Shortly afterwards, he murdered five other people, four men and a woman, and, when cornered by the police, attempted to shoot them also. At his trial, overwhelming evidence was produced, including the yard-long length of soiled cloth he had forced down the throat of Jean de Koven, and the verdict of the court was a foregone conclusion: death by the guillotine.