Execution: A Guide to the Ultimate Penalty (28 page)

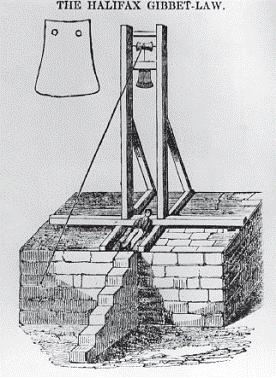

HALIFAX GIBBET

‘The block wherein the axe is fastened doth fall with such a violence that even if the neck of the transgressor be as thick as a bull, it would still be cut asunder and roll from the body by a huge distance.’

‘From Hell, Hull and Halifax, good Lord deliver us!’ runs the well-known phrase, as quoted from the

Beggars’ and Vagrants’ Litany

. Hell was feared for obvious reasons, Hull because, being well governed, tramps received short shrift and were driven from the town. Halifax was even more formidable, for its law decreed that thieves caught in the act would be beheaded.

The oddity of the latter was that an English town should have the right to execute criminals long after the Common Law of the country had abolished the privileges of feudal barons and lords of the manors. The established criminal justice at least assured them the right of trial by a judge skilled in the law, who would direct the jury. Yet somehow the right whereby Halifax could execute its own lawbreakers had slipped through the net, and over the centuries thieves apprehended there continued to be imprisoned, convicted by local people, and executed by officials of the town.

This ancient right seems to have been maintained in view of the conditions peculiar to the locality, when Halifax rose out of obscurity to become a major centre in the north of England for cloth-marketing. Nor did it apply only to the town which, in the fifteenth century, was just a hamlet of 15 houses, but also to the surrounding Forest of Hardwick. That was no small area, extending as it did from the town itself as far as 10 miles west to the border with Lancashire, although in width it stretched only 1 mile south of the town, and a mere 600 paces to the north. So an escaping felon who kept his sense of direction also kept his head! However, should the miscreant ever return of his own free will, and was recaptured, the gibbet awaited. It is recorded that a man called Lacy, ‘an abandoned scoundrel and thief, escaped; after seven years he thought it safe to return and that he would not be beheaded’. It wasn’t, and he was.

In the present age of travel it is hard to realise just how isolated Yorkshire once was, which could account for the continuity of the Gibbet Law. It was not only isolated by distance, for until the Dutchman Cornelius Vermuyden drained the wide-spreading fens to the south, Yorkshire was almost an island, the sea breaking on its eastern shoreline, the Pennines hemming it in to the west, and an almost impenetrable wilderness to the north.

A Parliamentary act of Queen Mary, which restored to Halifax weavers the liberty to purchase wool in small quantities, pictured the parish as ‘planted in great wastes and moors, where the fertility of the soil is not apt to bring forth any corn nor good grass, but only in rare places’. The preamble went on to say that by the exceeding and great industry of the inhabitants, who lived altogether by cloth-making, the barren land had then become much inhabited.

The rise to pre-eminence of the great cloth-manufacturing trade under the Tudors was the most important economic event in the West Riding of Yorkshire. The 40 years up to 1556 had witnessed the population of the Halifax woollen area increase by more than 500 households, each little manufacturer of a few pieces of cloth setting out in the open a wooden framework called a ‘tenter’ on which the cloth was stretched between hooks (hence the phrase ‘on tenterhooks’), so that it could set and dry without shrinking. Each frame was the length of a web of cloth, and they stood in rows, uncovered, in the tenter fields around the town. Being so distant from owner and cottage, they were a prime target for wandering rogues who, knife in hand, could quickly deprive the weaver of the valuable cloth he and his wife had fashioned so laboriously.

The only thing to deter such evil-doers was the Halifax Gibbet Law, which stated that any felon caught with goods stolen outside or within the said precincts, either hand-habend (carried in the hand) or back-berand (borne on his back), or who confessed to stealing goods to the value of thirteen-pence halfpenny would, after three market-days within the town of Halifax, next after apprehension, and being condemned, be taken to the gibbet and there have his head cut from his body.

The offender always had a fair trial, for as soon as he had been arrested he was taken to the lord’s bailiff at Halifax, and was then placed in the stocks in the market, which was held thrice weekly in the town, the stolen goods or animals being displayed next to him ‘both to strike terror into others, and to produce new evidence against him’.

A jury was then assembled by the sheriff, consisting of four freeholders from each of the villages in the liberty. The felon and prosecutors were brought face to face, with the stolen goods as evidence. If found guilty, he was remanded in prison for a week to prepare himself – or herself, it should be noted – for the approaching ordeal, and then taken along Gibbet Street to Gibbet Hill, where stood the dreaded engine.

Holinshed’s

Chronicles

, published in 1587, described the device in detail:

‘The engine wherewith the execution is done, is a square block of wood, of the length of four and a half feet, which doth ride up and down in a slot, rabet or regall, between two pieces of timber that are framed and set upright, of five yards in height.

In the nether end of the sliding block is an axe (blade), keyed and fastened with an iron into the wood of the block which, being drawn up to the top of the frame, is there fastened by a wooden pin, unto the middest of which is a long rope fastened.’

The actual procedure at an execution was best described by Dr Samuel Midgley who, while serving a term of imprisonment for debt in 1708, wrote a book entitled

Halifax and its Gibbet Law placed in a True Light

:

‘The Prisoner being brought to the Scaffold, the Ax being drawn up by a Pulley, and fasten’d with a pin to the side of the Scaffold; the Bailiffs, the Jurers, and the Minister chosen by the Prisoner, being always on the Scaffold with the Prisoner, in most solemn manner. After the Minister hath finished his Ministerial-office and Christian-Duty, if it was a Horse, an Ox, or Cow etc. that was taken together with the Prisoner, it was thither brought along with him to the place of Execution, and fasten’d by a Cord to the Pin that held die Block fast, so that when the time of the Execution came, which was known by the Jurers holding up one of their hands, the Bailiff, or his Servant, whipt the Beast, the Pin thereby being pluck’t out, and the Execution done. But if there be no Beast in the Felon’s case, then the Sheriff or his Servant cut the Rope.’

The Halifax Gibbet-Law

So the method of execution was, if nothing else, appropriate; had the thief stolen a horse or other animal, it would have the end of the release rope attached to its halter and would then be driven away, its departure pulling the pin out of its socket at the top of the block, thereby allowing the blade to fall and sever the thief’s head.

In cases where the theft had involved inanimate objects, an alternative method was sometimes used. Instead of the sheriff or his servant releasing the blade, the rope would be extended out into the crowd around the scaffold, everyone there either taking hold and pulling it, or stretching out their arm in its direction, as a token gesture that each was willing to see justice done. It could be said that that was a demonstration of true democracy, whereby society punished those who offended against its moral code; but the result would have been just as fatal had only

one

person pulled the cord.

Such was the height of the uprights that the speed of the blade’s descent was considerable, as Holinshed described: ‘The block wherein the axe is fastened doth fall with such a violence that even if the neck of the transgressor be as thick as a bull, it would still be cut asunder and roll from the body by a huge distance.’

That the head was catapulted away by the impact is also evidenced by a local historian’s account of a woman who was riding on horseback past Gibbet Hill while an execution was taking place. As the axe thundered down, its force propelled the severed head into the basket on the saddle in front of her. Constant recounting of this tale embroidered it with further gruesome details, describing the woman’s horror as the head, missing the basket, gripped her apron and held on with its teeth!

The parish register of Halifax contains a list of 49 persons who suffered on the gibbet, commencing on 20 March 1541 when Richard Bentley of Sowerby, in Yorkshire, met his end. Five persons were beheaded during the last six years of the reign of Henry VIII, 25 in the time of Elizabeth I, seven in the reign of James I, ten in that of Charles I, and two during the Commonwealth. Whether the comparatively small number executed can be attributed to the fleetness of foot by the felons or to the deterrent effect of the gibbet is open to debate.

Among those who suffered on the gibbet were:

William Cokere, headed the 9th daye October 1572