Execution: A Guide to the Ultimate Penalty (31 page)

Although representations were made to the Prince Regent appealing that, as in original applications of the death sentence, a knife be used for the beheading, his Royal Highness was adamant that an axe should be the symbolic instrument on this occasion. Two axes were therefore made, patterned on the one held in the Tower, and a gallows constructed outside the walls of Derby Gaol.

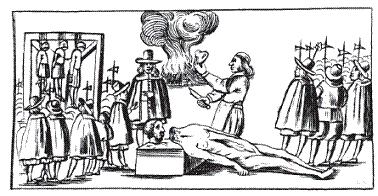

Whether drawn by curiosity or sympathy, great crowds assembled to see the three men, Jeremiah Brandreth, Isaac Ludlam and William Turner, led on to the scaffold. Without ceremony, nooses and blindfolds were put in place, and the condemned men were duly hanged, their bodies remaining suspended for an hour. A trestle, with a support at one end, had been placed in readiness on the scaffold, and on this the first body was placed, its neck resting on the support. A local miner, masked for anonymity, wielded the axe but, lacking the will or the expertise, failed with the first two blows, final severance being achieved with a knife.

No doubt coached by the authorities, the pseudo-executioner then lifted the head high and proclaimed the traditional announcement, but succeeded only in dispersing his audience as, overcome with horror at the ghastly exhibit, the crowd fled from the scene. With only the soldiers as spectators, the macabre drama continued, the other two bodies being cut down and similarly maltreated, all three cadavers then taken away for burial.

The last true performance of the brutal sentence took place in 1820, although the ‘disembowelling’ part was mercifully omitted. Again, social deprivation had bred discontent, this time in London, creating ideal conditions for the likes of agitators such as Arthur Thistlewood and his cronies. Believing that if the government could be brought down, revolution would triumph, the five conspirators plotted to murder the members of the Cabinet and to seize the Mansion House, the Bank of England and the Tower.

But the authorities, already appraised of the plans by an informer, were prepared, and the gang was trapped by the police in a house in Cato Street (now renamed Homer Street). On trial for high treason, all were found guilty, and at Newgate on 1 May 1820 they were greeted not only by a vociferous crowd of thousands but by the two Jameses, Messrs Botting and Foxen, the Finishers of the Law.

The latter officers waited until the condemned men had made their parting speeches and then proceeded with their duty, pulling on the legs of the hanging men to give them some assistance in departing this life. The crowd, far from patient, had to wait an hour before the bodies were cut down, and watched in awed fascination and horror as the corpses were positioned in their coffins so that the necks rested on wooden blocks. At that, a masked man, believed to be a surgeon, deftly decapitated each, passing the heads to Botting for the usual proclamation.

At that, the crowd, who would probably have welcomed the downfall of the government, to say nothing of access to the Bank of England, rushed the scaffold, screaming threats and imprecations. Botting and Foxen waited not but fled to safety within the walls of Newgate Prison.

Doubtless the scenes at this occasion bore fruit, for no further sentences of such barbarity were ever pronounced, the penalty being struck from the Statute Books in 1870.

Hanged, drawn and quartered

HANGING

‘What, dost thou intend to choke me? Pray fellow, give me more rope... How long have you been executioner, that you know not where to put the knot?’

Given a well-forested country, a large number of felons to be dispatched every year, a plentiful supply of ropes, and there was no doubt about the best method of execution to adopt – throw a rope over the branch of a tree and hang them! And as these conditions applied to most countries, so hanging became the cheapest and easiest method of execution, one that has continued right up to the present century.

The practice has been standard in Britain from time immemorial, but one restricted to common criminals, aristocrats having the privilege of the axe. In earlier centuries more than 200 offences, from petty pilfering to murder, carried the death penalty, some of them more unusual than others, one being reported in Stow’s

Annals

: ‘On 26 day of September in anno 1564, beying Twesday, were arraynyd at ye Gyldhalle of London, four persones for ye stelynge and receyvynge of ye Queen’s chamberpot, combe and lokynge glasse...’

Barons, lords of the manor and even abbots of monasteries had their own private gallows with which to punish disobedient servants, poachers and vagabonds. Most towns were similarly equipped to deal with those who had failed to benefit from previous punishment periods spent in the stocks or pillory. There was never any shortage of candidates, especially during the reign of Henry VIII when, it is reported, more than 72,000 men were executed on the scaffold.

Just as nowadays London, being the largest and most populous city, is reputed to have the best cinemas and theatres, so in past centuries it boasted the best hangings, many of them multiple events attracting large crowds. At one time in the city, offenders were hanged at the scene of their crimes, but the vast majority of felons were hanged at Tyburn, at what is now the junction of Edgware Road and Oxford Street (the latter then called Tyburn Road), adjacent to Marble Arch. A stone set into the central road island there bears an inscription to that effect.

In the twelfth century Tyburn Fields originally consisted of about 270 acres of rough ground through which the River Ti or Ty-bourne flowed. Rows of elms bordered this water-course, a tree of much significance to the Normans, who considered it to be the Tree of Justice, and elms are also indicated on ancient maps as growing on Tower Hill, where executions also took place.

It is estimated that over 50,000 people died a violent death at Tyburn between 11 per cent and its last use in 1783, but, as few official records were kept, the real total is probably considerably higher.

Originally, felons were hanged from the elm trees there, but eventually a more permanent arrangement was deemed necessary. The main road from the north entered London at that point, as indeed it still does, and so the site of the executions acted, hopefully, as a deterrent to travellers heading into the city.

Those awaiting execution were held in the various prisons which, in those days, were situated mainly in the old gates of the Roman wall. Heavily fortified, these were ideal and almost escape-proof; they were also primitive, dirty and disease-riddled. The major gaol was Newgate, which stood, appropriately enough, where the Central Criminal Court, the Old Bailey, now stands, the word ‘bailey’ meaning a castle wall. Those destined for Tyburn Tree, as its gallows were known, were brought from Newgate or the Tower, thereby enriching the English language with the doleful phrase ‘gone west’. Another phrase – ‘in the cart’ – refers to the hangman’s cart, or tumbril, although before such luxury travel the criminal was simply dragged three miles along the filthy streets behind a horse.

As this occasionally resulted in the premature death of the condemned man, to say nothing of the violent disapproval of the vast crowds who had been waiting since before dawn to watch the spectacle, so an oxhide or a hurdle was provided. Then it was realised that such a ground-level form of transport deprived all those spectators lining the route, other than those lucky ones at the front, from seeing the poor wretch, and the hurdle was superseded by the cart.

Other advantages immediately became apparent, for the cart thereby provided accommodation for the felon’s coffin, a clergyman or two, and of course the executioner. The condemned man himself was the centre of attraction, glorying in his moment of adulation; usually clad in all his finery, like a star at a rock festival, his elegant appearance being somewhat marred by the noose around his neck and the remainder of the rope twined about his body, he would play to the crowd for all he was worth, waving at the women, making speeches, acknowledging the plaudits for his apparent unconcern and bravery.

This attitude called for a considerable effort for, apart from his approaching demise, he had had a rotten night. As if tension in the prison had not been bad enough, a further ceremony had taken place at midnight, thanks to Robert Dow, a merchant who, in 1604, bequeathed an annuity for a bellman to prepare the ill-fated felon for the next world. This was done by the man visiting the gaol at midnight prior to execution day, ringing a handbell loudly at a window grating, and exhorting:

‘All you that in the Condemned Hold do tie, Prepare you, for tomorrow you shall die; Watch all and pray; the hour is drawing near That you before the Almighty must appear. Examine well yourselves, in time repent, And when St Sepulchre’s bell tomorrow tolls The Lord above have mercy on your souls. Past twelve o’clock!’

Today’s visitors to the church of St Sepulchre, which stands opposite the Old Bailey, will find, attached to a pillar at the east end of the north aisle, a small glass case containing that very handbell. The annuity also provided for the ‘passing bell’, the great bell of the church, to be solemnly tolled as the procession assembled outside Newgate Prison, while further prayers were chanted. Finally, in the words of Stow, ‘at such time as knowledge may be truely had of the Prisoners execution, the sayd Great Bell shall bee rung out for the space of a quarter of an houre so that people may knowe the execution is done’.

At one time the news of the actual moment of execution was transmitted by a pigeon which, on being released at Tyburn, flew back to Newgate so that word could be passed to the bellman, the equivalent of the present-day ‘We have just received a newsflash...!’

As to be expected in those days of minimal entertainment as we know it, every execution brought a great turn-out. Crowds lined the streets, thousands more at the scaffold site itself, on balconies and rooftops, workmen and apprentices, shop assistants and merchants, lords and ladies in their coaches, the latter having brought wine and food hampers, the former having to make do with hot potatoes, fruit and gingerbread-men hawked by the many vendors, the lower classes passing the time by drinking cheap gin and fighting, or reading the pamphlets bearing the victim’s ‘Last Dying Speech’ that were on sale.

Grandstands had been erected by entrepreneurs known as Tyburn ‘pew openers’, charging exorbitant prices for the seats when a particularly famous or infamous felon was doomed to die, in the same way as ringside seats cost more when a boxing championship match is staged today. One speculator, Mother Proctor, made a commercial killing, appropriately enough, when an earl was executed, reaping a profit of £500, but it wasn’t always easy money. In 1758 Mammy Douglas increased the price of her stand seats for the hanging of Dr Henesey, guilty of treason. Despite protests, the public, as usual, paid up, but their indignation turned to fury when, just as the hangman was about to execute the victim, a messenger arrived bearing a reprieve! A riot ensued, the stands were demolished by the mob, and the attempts to hang Mammy Douglas instead were narrowly averted.

Meanwhile, the execution procession would be wending its slow way towards Tyburn, one or two stops being made for refreshments. One halt was at the hospital of St Giles in the Fields, outside which they were all ‘presented with a great bowl of ale, thereof to drink at their pleasure, as to be their last refreshment in this life’, the practice perhaps giving rise to the phrase ‘one for the road’. One condemned man, Captain Stafford, his morale undaunted, asked the proprietor for a bottle of wine, saying that although he had an appointment to keep, he would pay the landlord on the way back! A less cheerful case, and one that poses a fearful moral for teetotallers to ponder, was that of a felon who refused the fortifying draught and was duly hanged: within a minute or two of his death, however, a horseman arrived bearing a reprieve. If the victim had only paused for a drink... This custom of stopping for refreshments ceased in 1750, although a tavern named The Bowl was later built on the site of the old hospital.

Meanwhile, at Tyburn all would have been made ready for the hanging, the tension really erupting into frenzy on the arrival of the procession, a cacophony of cheering and jeering as the spectators jostled to improve their view, shouts of ‘Hats off! Hats off!’ as the cart drew up to the execution site, not so much a mark of respect for those soon to die, but demands by those whose view was impeded by the headgear of the people in front.

In the early part of the twelfth century the gallows consisted simply of two uprights and a cross-beam capable of accommodating ten victims at a time. The

modus operandi

was simple: the felon would be made to mount a ladder placed against the cross-beam; the hangman’s assistant, having swarmed up on to the cross-beam, would attach the rope to it; and the hangman would then twist the ladder, ‘turning off the victim so that he swung in the empty air, his eventual death coming by slow strangulation.

Until about 1870 the rope was tied with a hangman’s knot to form a running noose, the weight of the body keeping it tight, and up to 20 minutes could elapse before breathing stopped. As a concession the hangman would permit the victim’s friends or servants to hasten death by pulling the victim’s legs or thumping his chest, and usually the body was left hanging for an hour before being cut down. During that time a bizarre custom was enacted, women rushing forward to seize the still-twitching hand of the dying man and press it to their cheeks or bosoms as a cure for skin blemishes; children would be lifted up to have the ‘death sweat’ transferred to their infected limbs, and even splinters from the gallows were believed to be a certain cure for toothache.

There was also a flourishing sale of short lengths of the rope, another perquisite of the hangman. The more infamous the felon, the dearer and the shorter the length of hemp, though in some cases the total length sold could easily have encircled Westminster Abbey!

A lady who survived despite the sympathetic efforts of her friends to expedite her demise was Anne Green. She had been sentenced to death for killing her newly born child.