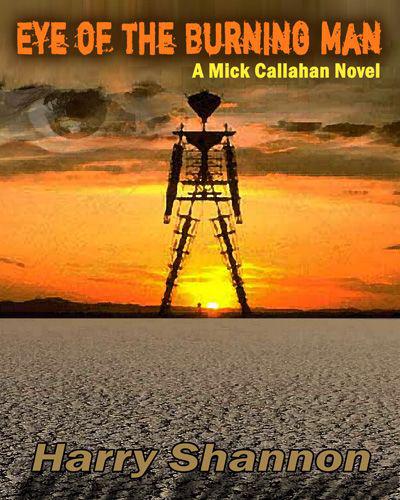

Eye of the Burning Man: A Mick Callahan Novel (The Mick Callahan Series)

Read Eye of the Burning Man: A Mick Callahan Novel (The Mick Callahan Series) Online

Authors: Harry Shannon

Tags: #FICTION / Thrillers

EYE OF THE BURNING MAN

A Mick Callahan Novel

By

Harry Shannon

This one is for my daughter, Paige.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

"Eye of the Burning Man" is a work of fiction, and the resemblance of any character to an actual person, living or dead, is coincidental. Even the geography described has been aggressively altered for dramatic purposes. I wish I could say the same for most of the statistics regarding child pornography.

As always, I am grateful to my wife Wendy for her constant support, blunt criticism, and endlessly creative suggestions.

The Burning Man Festival serves, for many people, as a both a significant counter-culture statement and a legitimate arts festival. No one should construe Mick's feelings about the festival as reflecting my disapproval.

Thanks also go to the following friends (in no particular order) for reasons they will understand: Joe Donnelly, Jennifer Davila, Joan Bellefontaine, Leyna Bernstein, Lynwood Spinks, John and Jill Boylan, Judd and Dory Kramer, Dr. Paul Manchester, and my gal pal and fellow author Gina Gallo.

Gracias

to my English teacher back in 1963, a man named Dennis Kelly. He made me want to write.

Gracias

to my English teacher back in 1963, a man named Dennis Kelly. He made me want to write.

Finally, I'm grateful to the many mystery fans and small book sellers who have supported Mick Callahan and helped to spread the word about his exploits. I can't thank you enough.

© 2010 Harry Shannon

"The world is suffering—

The cause of suffering is desire."

—The Buddha (250 BCE)

"Go without hate, but not without rage.

Heal the world."

—Paul Monette

PROLOGUE

Panorama City, California, July 4th

A fat woman stepped out of the meager shade of a withering lemon tree. "

Madre de Dios, esta muy caliente a hora,"

she whispered; Mother of God, it is hot! She turned the hose on herself for a long moment. The cool water caused her huge breasts to bounce like beach balls in the blue patterned dress. She shook like a lazy, wet dog and went back into her home to open another can of Cerveza.

Madre de Dios, esta muy caliente a hora,"

she whispered; Mother of God, it is hot! She turned the hose on herself for a long moment. The cool water caused her huge breasts to bounce like beach balls in the blue patterned dress. She shook like a lazy, wet dog and went back into her home to open another can of Cerveza.

The sun had scorched the tattered roofs of the bleached-out, pastel barrio homes, causing tempers to flare and copious amounts of cold beer to vanish. There was no wind, and the 106-degree temperature squatted on the San Fernando Valley like a living thing. Filthy fans whirled like perpetual motion machines in splintering window frames. Even the ice cream carts were sweating.

Harvey Street is a few blocks East of Sepulveda Boulevard, and several north of Saticoy. That summer day, four brown boys in white, sleeveless undershirts ran back and forth through the lawn sprinklers, playing soccer with a flaccid volleyball. They were all under ten years old.

The smallest began to gasp. The largest stopped the game at once, ignoring the howling protests of the other kids, and ordered his tiny friend to sit. No one dared to challenge him. The leader's name was Manuel, but his friends called him

"Loco."

"Loco."

Loco was a dark, wiry boy. He looked around, searching for something, anything to do. "The air is foul with smog. Take a moment and rest your lungs."

"We were winning," another boy said. "It is not fair to stop now."

"You would have lost anyway," Loco said. He pounded his chest like an ape, drawing laugher from the others. "I personally would have defeated you. Unlike you, I was only pretending to be tired."

The spell was broken. The boys sat quietly in the cool mist from the lawn sprinkler, waiting to be chased away, wondering what to do next. Loco fixed his eyes on a battered fence surrounding a lot overgrown with weeds, land that held the wreckage of a former crack house. His eyes narrowed. He rose.

"No, Loco," said Jose. He was pudgy and round and had a flat Indio nose. His family had recently arrived from Guatemala. "Don't even think about it,

ese. No entres alli

!"

ese. No entres alli

!"

"Why not go?"

"

Malas cosas an pasado alli

," Jose said. Because bad things have happened there.

Malas cosas an pasado alli

," Jose said. Because bad things have happened there.

Another boy said: "A monster lives in that house. I can hear noises at night from my bedroom window.

Mi mama dise que los ninos que entran alli nunca salen!

" My mother says children who go in there never come out again.

Mi mama dise que los ninos que entran alli nunca salen!

" My mother says children who go in there never come out again.

"You mother is a fool," Loco said. "The North Hollywood Boys use that house to party."

"That alone should frighten you," Jose said.

"

Todos ustedas son corbardes

," Loco said. You are all cowards. He threw back his head. "

Yo soy un hombre valiente

!" I am a courageous man.

Todos ustedas son corbardes

," Loco said. You are all cowards. He threw back his head. "

Yo soy un hombre valiente

!" I am a courageous man.

The others watched him stroll across the blistering blacktop, his wet sneakers making a sound like sloppy kisses. He approached the boarded-up lot. The old fence had been tagged more than a dozen times. Loco paused by the huge NHBZ sprayed in black paint. He could hear other boys following. He resisted the temptation to look back over his shoulder. A man must be careful of his reputation.

Loco kicked at a board, careful not to pierce his shoe with a rusty nail. He swallowed his fear and prepared to step through the space and into the fetid blackness.

"

Espera cara mi aqui si quieres

," he called out, bravely. Wait for me here if you want to. He moved through the fence.

Espera cara mi aqui si quieres

," he called out, bravely. Wait for me here if you want to. He moved through the fence.

The smell hit him instantly, a stench like bad sandwich meat. Loco recoiled. Something dead was rotting away. His mind conjured bloodless human bodies in grotesque poses, stacked together like butchered pigs. He almost ran, like a foolish woman.

He told himself the gang arranged such things to strike terror into the neighborhood. It was probably just the carcass of an animal, something they had found dead in middle of the road. He approached, and forced himself to look down. It was a decaying possum, stiff with rigor mortis, horrid teeth bared in a final act of defiance. Loco pinched his nostrils and moved past it, going further into the gloom.

Broken, splintered boards lay scattered about, along with rags and cans of spray paint. His eyes became accustomed to the gloom. The NHBZ logo was everywhere. Empty whiskey, wine, and beer bottles lay in shattered piles. Some baseball bats were arranged in a neat row along the edge of the porch. The front door, smashed down long ago by a police assault, lay flat in the dusty living room. Loco felt something go

snap

beneath his feet. He looked down.

snap

beneath his feet. He looked down.

Although Loco had yet to do drugs, except for a bit of weed, he recognized the burnt glass tube as a crack pipe. Cocaine had destroyed his life. His father had gone to prison, and his mother had gone to rehab. Now he lived here, with his aunt. He spat in the dirt and wiped his hands on his jeans.

Loco went up the steps and into the house. Used condoms lay everywhere, along with small compact mirrors, cut straws, and tiny brown bottles which had once held mysterious powders. The NHBZ had been quiet for the last few weekends. It probably wasn't crystal Meth. If they had been smoking or snorting crystal, there would have been violence and people would have gone to the emergency room.

CRAAAAACK. A board snapping.

Dios Mio!

Was that someone coming through the back yard toward the house?

Dios Mio!

Was that someone coming through the back yard toward the house?

Loco tried to move quietly, but quickly, back to the front of the building. He tripped. His elbows came down onto a faded stack of Penthouse magazines. Dust flew up and into his nostrils and he fought back a sneeze. Something many-legged and hairy ran across his arm and down into the magazines. Loco stifled a shriek.

The tarantula was huge. He was fortunate not to have been bitten. He slipped back out onto the front porch, dashed for the fence. Behind him he heard several gang members stumble into the house from the back entrance. They were obviously drunk. Loco knew that he had nearly been caught. He blew out a long breath and then pushed a board aside, seeking the friendship of sunlight.

A face glared at him from the other side. Loco gasped.

It was Jose. "Loco, are you okay,

ese

?"

ese

?"

"

Yo estoy bien, idiota!"

Loco hissed. "I am fine, you idiot.

Estaba facil

, it was easy. Now get out of the way, some of them are right behind me."

Yo estoy bien, idiota!"

Loco hissed. "I am fine, you idiot.

Estaba facil

, it was easy. Now get out of the way, some of them are right behind me."

Giggling, the four boys raced across the street and back into the tepid water. Loco washed his face and hands and tried to cleanse himself of the sweat and fear. He could still smell the stench of the dead animal that lay rotting near that cursed house.

"

Tu eres llamado Loco?"

Tu eres llamado Loco?"

The boy turned. He saw a tall, powerful gringo with a shaved head and a nose ring. He was considerably older, and he sat behind the wheel of an old Dodge Dart. He seemed tense.

"They call me Loco," the boy said proudly. "Why?"

"Escucha me,"

the man said. He spoke badly, with a piss-poor accent. "

Tu mama me a mandado

." Listen to me. Your mother has sent me here to find you.

the man said. He spoke badly, with a piss-poor accent. "

Tu mama me a mandado

." Listen to me. Your mother has sent me here to find you.

Loco narrowed his eyes. "I don't live with my mother," he said with a sneer. "My mother is away. That woman is my aunt. Go away, pervert."

He turned his back. The boys, emboldened by their number and their distance from the vehicle, began to jeer. They called the man

maricon

, faggot, and other names. He did not seem angered.

maricon

, faggot, and other names. He did not seem angered.

"Suit yourself," he said. He gunned the engine. "I was only doing her a favor."

"Do us a favor and fuck off," Jose said. The boys laughed again.

"Just so you know, Loco," the man said, "

Tu gato a sido atropellado."

Your cat has been hit by a car.

Tu gato a sido atropellado."

Your cat has been hit by a car.

Loco stepped back, shaken. He regained confidence. Said: "

Como se parese migato? Estrano

." Okay stranger, you tell me what my cat looks like.

Como se parese migato? Estrano

." Okay stranger, you tell me what my cat looks like.

"Right now? A bloody black and white bag of shit," the stranger said. He shrugged with indifference. Then, in broken Spanish: "

Gato gordo. Negro con ples blancos."

Gato gordo. Negro con ples blancos."

Loco loved his animals. He approached the car warily.

"

Corre!"

shouted another boy. Let's run away!

Corre!"

shouted another boy. Let's run away!

But Loco moved closer to the car. He leaned into it urgently. In low tones, he said: "When did this happen?"

The muscular stranger grabbed the boy by the hair and yanked him into the car. A woman appeared in the back seat and tried to jam a rag over his mouth. Loco struggled.

"Ayudame!"

he screamed. But the car was already away from the curb, gone with a squeal of brakes and a blast of black exhaust. The rag covered his nose. It smelled foul, thick with a chemical stench. The world spun away.

"Ayudame!"

he screamed. But the car was already away from the curb, gone with a squeal of brakes and a blast of black exhaust. The rag covered his nose. It smelled foul, thick with a chemical stench. The world spun away.

The gringo police came. They brought an older officer with Mexican blood. He acted very concerned. They put rows of yellow tape everywhere in the yard, and took a lot of pictures. They used this excuse to roust the North Hollywood Boys, although they already knew that this particular perpetrator was a white man. They saw every neighbor willing to talk to them, and then they went away again.

The aging detective of Mexican descent spoke to Loco's aunt, Blanca, even held her while she sobbed. He stayed the longest. One could see he was deeply troubled. He assured Blanca that he and his department would do all they could to find the boy.

As he and his partner walked back down the sidewalk, the Mexican-American detective lit a cigarette. He swore under his breath.

"What's the matter?"

"I'm getting too old for this shit."

"I know," said the partner. They got into the sedan. He started the car. "It sucks, doesn't it?"

"Damn right. One more kid who was born to end up on a milk carton."

The story made the evening news, but it wasn't unusual enough to dominate the headlines for long. Not with Iraq in flames and the economy in a slump.

ONE

Northridge, California, August

It was an ugly, sweltering summer. Maintenance had set the thermostat in the booth for seventy degrees, but it was humid as hell and I was soaked with sweat. The heat of the San Fernando Valley rivaled a nasty season in a faraway place like Nashville or Miami.

"Good evening. You're on the air live with Mick Callahan, so be sure to turn your radio down." I watched a drop of perspiration roll from the tip of my nose to splat on a lined yellow note pad, smearing the ink where, for the last two hours and forty-five minutes, I'd scribbled catch phrases, reminders, and first names. I looked up and through the tinted glass partition, at my date.

Other books

Priceless by Richie, Nicole

Obsidian Beauty (The Obsidian Series Book 1) by Emily Walker

Stuck in the 70's by Debra Garfinkle

Nadia Knows Best by Jill Mansell

Delta Ghost by Tim Stevens

Charlie by Lesley Pearse

受戒 by Wang ZengQi

The New Rules for Blondes by Coppock, Selena

Outpost: Life on the Frontlines of American Diplomacy: A Memoir by Christopher R. Hill

A Long Strange Trip by Dennis Mcnally