Fairytales for Wilde Girls (3 page)

Â

A Picture of Isola Wilde as Viewed by a Sober Edgar Allan Poe

He recognised her immediately. The dark and the noise and the liquor could only camouflage so much. Cinderella's day-time disguise was a girl with:

⢠origami hair, as though some enthusiastic Japanese schoolgirl had tried to fold each section into a variety of animal shapes. It'd come up wild instead, a veritable safari. Her body seemed tiny and impeccably neat by comparison.

⢠arched eyebrows, pencilled the colour of Swiss chocolate, a shade too dark for her dyed hair.

⢠oodles of scarlet ribbons woven through her white-goldilocks.

⢠bare feet and a cream-froth dress that were Woodstock-muddy.

And she was alone â excluding the pathetically wilting plum tree â and looked for all the world content with her own company.

Â

Boy â An Appraisal

Isola Wilde knew perfectly well that appearances told you nothing about a person, unless the only thing you were interested in was establishing from their attire what period they died. Nevertheless, she noticed several key things about Edgar Allan Poe's appearance that she hadn't in the smoggy microcosm of the Big Party's kitchen the night before.

He was big. Tall and broad with meaty hands, a slight pudginess about him.

He wore braces â like a mouthful of diamonds in the sunlight.

Large round ears, sticking out and ending in slight elfin points, a changeling baby's.

A battle helmet of curly black hair.

Distinctly rounded shoulders, as if slouching would somehow make his overall size less noticeable.

âGoing to give me your real name this time, bright eyes?' the boy called.

Isola felt a smile curling her lips. âIsola Wilde.'

She knew he didn't believe her when he replied, âI'll call you Number Thirty-six, then, shall I?'

âAnd you must be the new Number Thirty-seven.'

Edgar Allan Poe/Number Thirty-seven bowed in acknowledgement. A Playstation controller fell out of the BODY PARTS box and he hastened to pick it up.

âEdgar!' A middle-aged woman emerged from the house with fresh paint stains over her smallish baby-bump and a relaxed slouch that mirrored her son's. âI need you â Portia's getting into the silverware and you know how she is with knives!'

Edgar Allan Poe waved at Isola again, almost dropping the box. He struggled to heave it higher. âSee you round, Annabel Lee.'

Isola returned to the tree, lacing reams of golden bells through the branches.

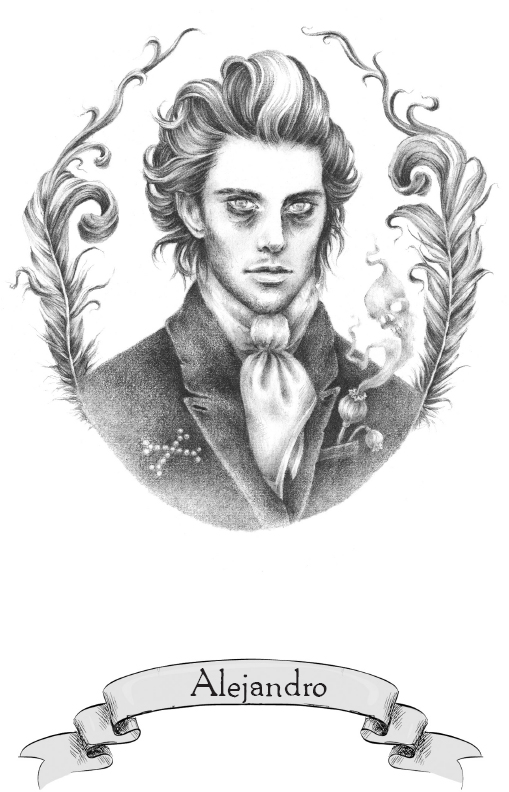

âYou told him your real name,' said Alejandro quietly.

He was rearranging tinsel, his face obscured, but Isola knew from his tone what his expression would be like. She could sense it, slight on the wind, if she sniffed: jealousy, mixed with a heady dose of love and a strong desire to protect her. Not just from scrapes and sickness and televised suicides, but from boys, from men.

Alejandro had been Isola's brother since she was four years old. Her favourite brother, and the first of six.

Â

Â

Â

Isola Isolated

There had been an Isola Wilde once before, dead at the ripe old age of nine in the year 1867. The famous Oscar's baby sister. The second Isola was named for her.

Isola's mother loved Oscar Wilde. If he weren't both gay and deceased, she always said, she would have married him in a Victorian heartbeat. Modern Isola often wondered what nineteenth-century Isola would have been like had she grown to a more respectable age. Nine years old. Each year lived like a cat's life.

The second Isola thought the first Isola â the

real

Isola Wilde â would have grown into a remarkable lady, if given a sporting chance. A playwright, a poet, an artist. She would have been quick with a quip, like her brother, and written twisted, haunted books with velvety lesbian undertones, and maybe even been thrown in jail for it, too.

The second Isola didn't die at nine. At her tenth birthday party, on a lawn scattered with children clutching fistfuls of frosted cake and rapidly deflating balloons hovering at ankle-height, Mother Wilde sat in the dewy shadow of a plum tree and drew Isola on to her lap, whispering in her ear that she must live twice as hard on behalf of her tragic forebear.

Teenage Isola wore too much make-up and was almost uncomfortably skinny, her long limbs bunchy, stuffed with straw â like a voodoo doll of a popular girl.

She lived in black-laced army boots and periodically invented her own fashions. She was only recently sixteen, and she had a secret universe a doctor once called a âfantastic flight of fancy'. Her parents had long since abandoned the doctor's suggestion to encourage and play along â and yet it was still real, often more solid to her than the planet under her feet. Her middle name was Lileo. Pronounced

Lie-lee-oh

.

Isola loved things that other people didn't, especially when it came to body features. Like overbites and freckles and rounded tummies, stretchmarks and birthmarks and pigeon toes and ears with elvish points.

Mother Wilde always said a beauty flaw was a beauty

fluke

. A good thing.

Flaws mark the flakes

, she would say. Meaning flawed people are like snowflakes. Unique. Or maybe frozen.

Isola Wilde was frozen. If she licked her wrist she tasted seasalt. She knew exactly how she had come to be an ice girl. She remembered it like an old movie, a past life.

A sculptor had carved her from a block of the berg that sunk the

Titanic

. He made her in the image of his daughter, dead when her lungs swelled with blood â the dainty cough into the handkerchief, the same little spot of crimson that had taken her mother.

Completed, the sculptor moved Ice Princess Isola from his eternal winter workshop and into his little cottage by the bay. In the dead winter, which was as cold and tempered as the wedding veil of a bride left at the altar, he couldn't bear to light the stoves and fireplaces and see the tears dripping from the sculpture's pores, her frozen hands â blood running from a lifeline.

At winter's end they found the sculptor blue, chill-poisoned, and the ice girl was smiling wicked-frozen forever, so perfectly formed that they thought it a shame to hide her in the cold cottage overlooking the sea. They mounted her instead in the village square, and not one summer did she so much as break a sweat.

But that was only a fairytale.

Â

The Dead Girl

As she walked to school on Monday, Isola found a dead girl in Vivien's Wood.

The emaciated body, Holocaust-thin, was hanging from a tree. Not by a rope or a Rapunzel braid â she was stuffed inside a child-sized birdcage, cramped against the paint-flaked bars, one striped-stockinged leg hanging down and swaying like a pendulum.

Before she had discovered the corpse, Isola had been on a mission. She had deviated from her usual trail, following signs of the rarely seen herd â a possible glimpse of a rainbow tail, the tease of soft clopping up ahead. She knew for certain they were out here, but they had been scarce for years now, and she never seemed to spot them â

her

, the only girl in Avalon that even knew about the unicorns!

But the herd was forgotten as Isola stood under the cage and counted the number of times the leg swung, the crooked minutes it ticked by. She couldn't see the corpse's face, only a scrub of dirty dark hair, a grey dress. She examined the tarnished silver buckles on the black shoes, the ladders in the stockings. She reached out hesitantly.

âIf you dawdle any longer, you will most certainly be late.'

She hadn't heard Alejandro appear so suddenly beside her, the way a shadow does in the midday sun. Isola dropped her outstretched hand and pressed herself against the tree trunk. The twisted dizzy branches seemed to close over her, a witch-fingered hug.

âGo along, now,' said Alejandro. He was peering up through the branches, his dark eyes searching for the bough that held the cage aloft.

âBut I can't just leave her,' insisted Isola. âI have to help her down.'

âShe is beyond even your help,

querida

,' said Alejandro softly. âGo, I will stay with her. I must see . . .'

Isola knew better than to argue with the wisest and most stubborn of her brothers. She crunched across the forest carpet, glancing back at Alejandro, who stared up as if hypnotised at the figure in the birdcage.

She knew what he needed to see. Whether the girl would return. Whether she would haunt.

Sometimes it was hard to tell what was corpse and what was ghost.

But ghosts did not frighten Isola Wilde. They never had.

Dramatis Personae

ALEJANDRO:

The first prince. A beloved guardian and ghost of a young man.

DEAD BODY:

A girl, a cage, a mystery.

Four was the age when Isola first starting seeing ghosts; at least, that's the earliest she could remember. Alejandro was the very first she had ever met. A dashing young man from Victorian London; beautiful, with his mother's Spanish colouring, the dandy dress and aura he'd inherited from his peacock-strutting father. He died aged twenty-four in an opium den, soaking into death as he lay in a pool of absinthe and dyed ostrich feathers â the same way he'd spent most of his short life.

Â

Â

St Dymphna's Ladies College was staffed by nuns. A few of them still taught and the rest merely flitted like rumours on the ground, only glimpsed in slices of life â sagging grandma bras strung on a washing line in a hidden courtyard, baskets of lemons left in the locker room, candles burning lonely in the little chapel at all hours.

It was strange to be back again. Somehow, every time Isola passed through the iron-wrought gates at the end of the school year, she couldn't imagine returning in autumn. The final clang behind her seemed like a closing of a chapter, heralding a blank page to scribble on. But here she was. Grape had made good on her word, and Isola had sat beside an empty desk throughout the morning's classes.

While entering the school chapel during break, Isola passed Sister Marie Benedict in her old-fashioned habit. The nun jangled as she walked, and Isola couldn't decide if the rhythm came from her old bones scraping in lube-less sockets or from the clatter of rosary beads looped around her liver-spotted neck. Catching Isola's gaze, Sister Marie hastily crossed herself.

Isola was alone, breathing the musty candlewax and angel-dust air, inhaling the scent of sweat from a thousand past hands clasped tightly in prayer, dirt rubbed from the knees of sinners. Isola went to look at the saints' portraits on the chapel walls; daubed white faces turned heavenward, flanked by Raphaelite angels in full crusade garb, swords flaming from the hilt.

The school's namesake adorned the hallways; the frail Irish girl, only fifteen, holy in her portraits and decapitated in her grave. Dymphna was the patron saint of princesses and the mentally ill â there was a lovely dichotomy at work there, and she was one of the very few things Isola liked about religion, the other being the chapel. Even at her loneliest, Isola somehow felt the painted girl on the walls was on

her

side.

Someone had attached a sticky-note to the frame of St Dymphna's largest portrait. Isola peered closer. Written in a speech bubble, as though the painted girl was beseeching any student that wandered upon her, â

Hey girl! Don't lose your head!

'

She giggled, and the sound echoed, a haunting. No wonder Sister Marie had crossed herself upon eye contact. Isola made sure not to dip her fingers into the tiny pool of holy water on the way out; if it didn't acid-burn her skin off, it'd at least zap her good. A static charge instead of a lightning strike. Fair warning.

The bell rang, spurring a flurry of activity in the corridors, and Isola was heading to class when something black caught her eye on the third floor. A molten, tarry substance was seeping under the door of the unused bathroom. Oblivious girls stepped in it, but it did not splash or ripple; instead it merely trickled closer to Isola.

The light flickered in the hallway.

The masses of blue-clad girls were swirling, funnelling into the classrooms, while Isola stood stock-still, a pebble unmoved in a brook.

She waited until the stragglers had dispersed, then cracked open the bathroom door and remembered why it went unused. Dank and gloomy; the walls were graffitied with declarations of love, accusations hurled at other girls, and crude cartoons of the nuns. There was a great rusty bin on the wall (an old-fashioned incinerator for âsanitary purposes'), which smelled smoky even though it was never switched on. The ugly neon light in the room flickered too, casting horror-movie lighting upon the damp floors and the two figures in the room.

The woman in black stood with her back to Isola, gazing at herself in the spotted metallic mirror until she met the reflection of Isola's eyes.

âRuslana!' Isola said in surprise.

Dramatis Personae

RUSLANA:

The third prince. A Fury and a fierce warrior, whose promises to Isola are as solemn as blood oaths.

âHello, Isola.'

The light bulb flickered like moth wings. Ruslana was an entity of the dark, and the light was clever enough to avoid her â even the electrical kind.

Of her six brother-princes, Ruslana was the most frightening, the most powerful. She seemed human enough, until closer inspection. Dark eyes sewn-in deeply, like pebbles fetched from the bottom of the ocean. Talons in place of fingernails. Coarse black hair she never combed, perched in a high braid. Eyes lined heavily in black, and faintly tattooed forearms. Berry-black lips, razor-edged, capable of severing a limb. Coloured jewels studded her earlobes and weapons were hidden all over her body, contoured to her shape.

She had a great oil-spill of a cloak; the edges crept about like autonomous shadows, enfolding everything they came across. She had once shown Isola a picture of the Furies in the old Greek books; bird-like crones who killed men solely because of their Y chromosome. Ruslana had a more particular purpose.

And now she stood there in her dark garb, harnessed waist, the skirt split to the thigh and the silver breastplate echoing the warrior. Not a spectre, because she had never been human, but a spirit of women's vengeance.

But even she wasn't exempt from Alejandro's rules.

None of Isola's secret brothers ever visited her at school, no matter how nervous she was about an upcoming speech, or how much they wanted to see her trip hurdles in the Autumn Athletics Carnival. Alejandro had put his foot down long ago â her life with brothers and her life without would remain resolutely separate.

âShe cannot hope to fit in,' he'd said to them at the time, âif we help her stand out.'

âWhat are you doing here?' Isola tried not to sound too excited. It couldn't be good news, after all, to warrant this unprecedented visit, but her heart still dropped when Ruslana sighed heavily and lowered her hood. The night cloak swirled around her before settling into even deeper darkness.

âIt's about that girl,' said the Fury in her coffee-grinder voice. âAlejandro showed me to the body.'

âDid you find out what happened to her?'

Ruslana nodded solemnly. âThe birds know,' she said. âThey have been spreading it to the fae, and the faeries were very, well, excited to tell me.'

âSounds about right,' scowled Isola. They really could be wretched creatures; sometimes they seemed

too

pleased when terrible things happened . . .

âOh, don't hate them, Isola,' Ruslana gently scolded. âI know they're overdramatic little things, but I don't think they'd lie about this. It could be very well embellished, though.'

âTell me.'

âThere's a witch,' said Ruslana, âin Vivien's Wood. Not a human â some kind of malevolent creature. They said she's not been there long, but she loves music, and all the birds in the woods have fallen silent â hiding because they're afraid of her. The witch kidnapped a girl with a beautiful voice and kept her in a cage, forcing her to sing for company. When the girl finally lost her voice, the witch left her to die.'

Ruslana leaned back further, crossing her impossibly long legs. She didn't know it, but she had fallen into the storyteller's cadence, altering her speech like Mother used to during her nightly performances in Isola's room. Of course, that was a very long time ago.

âAll the birds had been listening to the girl sing for weeks, maybe months. When her songs ended, they gathered around her cage and offered to bring her seeds and beetles so she might survive until she was rescued. But she told them, “Please, pluck out my eye, and take it to my father. He is a man of magic, and he will be able to use it.”

âThe birds argued and argued, but she croaked in her bloodied, ruined voice, “You must take my eye to my father, so he can see what I have seen. Then he will know who killed me.” So the sparrows and ravens plucked out the girl's right eye with their razor-sharp beaks, and in pity they pecked at the skin of her wrists, until they found the taut strings carrying the blood, and plucked them up like earthworms. She bled out quickly, half-blind and voiceless, and her eye was carried back to her father, the King of a small and poor county. He cried for his daughter, but he thanked the sparrows, and summoned the court shaman to perform the ritual that would allow him to see what the eye had seen. And reflected in the iris he saw the forest witch, who was also his first wife, the old Queen of the small, poor county â his daughter's mother. He saw her string their child in the tree, saw her force their child to sing her life away.'

Ruslana tapped her talons against the cracked porcelain sink, looking terribly despondent.

Isola frowned; it was a heart-wrenching story, as all untimely girl-deaths are, but the towering Fury had heard it all before and worse. What was it that made this particular incident have such an effect? âWhat is it, Ruslana?'

The Fury crossed her lean arms over her bodice, eyes downcast. âIt's too close,' she murmured after a long moment. âShe died in Vivien's Wood . . . I don't understand how I could have missed it.'

âYou're not responsible for every girl in the world.'

âI am for

you

. I shouldn't have missed this. I should have sensed her pain.'

A tiny tapping at the glass jolted them both. Ruslana's cloak had inked out the window, and she pulled the slippery material to heel, exposing the sunlight again. She went and cracked open the window. A minuscule bauble of pink light fluttered in, alighting on the Fury's shoulder.

âDid you tell her?' it squeaked breathlessly.

Dramatis Personae

ROSEKIN:

The fifth prince. A smart-mouthed faerie with a taste for dramatics.

âIsola? Don't you think it's exciting?' Rosekin went on, beaming. âA murder, right on our doorstep!' The bright bubble of light had abated, and the miniature girl-figure stood, clinging onto Ruslana's black braid. âIt's like one of those scary stories,' the faerie added, not bothering to suppress her glee. Isola supposed she was right â it did lend itself to an air of Grimmness â but

exciting

was not a synonym for this.

âOoh! Ooh! Isola! Rusly!' said Rosekin, tugging the Fury's hair when Isola didn't answer. âRemember, the

witch

is still out there, too!'