Fairytales for Wilde Girls (6 page)

Â

The Children of Nimue

Growing up, Mother Wilde had never been allowed a birthday party. Her own devout mother insisted the only person special and sinless enough to deserve an annual celebration was the baby Jesus. As an adult, Mother Wilde became famous in Avalon for throwing beautiful birthday parties for her only daughter â green lawns in high summer and sumptuous cakes frosted with Isola's newly achieved age. Mother Wilde invited everyone.

Isola's last birthday party had been her tenth. Mother was too sickly afterwards â after what happened.

But, in Isola's memory, the parties raged on. One of her favourites was her fifth. It was faerie-themed â the traditional kind, with traditional spelling â and all the girls wore floral crowns handcrafted by Mother, and the boys held kingly corsages and brandished Oberon sceptres.

Isola was busy greeting guests at the letterbox while Mother was ferrying the gifts to an ever-growing pile on a trestle table.

Mama Sinclair, the rotund Scottish nurse who lived at Number Thirty-nine, arrived wearing a floral sundress and a grin as wide as a loch. She had an enormous bosom and gave vigorous hugs, and that day she squashed Isola against her breasts even tighter than usual.

After the initial panic of torn paper and shredded ribbons, when all Isola's gifts were laid out on the grass for the other children to examine and play with, Isola noticed Mama Sinclair in a chair. She was sitting in the generous shade of the then-thriving plum tree, fanning herself with one chubby hand and cradling a small pink box in the other.

âCome, look what I have here for you!' she called, and Isola tottered over, plopping down at Mama Sinclair's feet expectantly.

Wolfishly, Isola tore at the package Mama Sinclair handed her to reveal a tarnished silver jewellery box.

âOh, that's beautiful!' said Mother Wilde, standing over Isola, a silhouette in the strong sunlight. âSay thank you.'

âThank you,' parroted Isola.

âIt plays music, too,' beamed Mama Sinclair. âGo on, Isola.'

Isola opened the box, and what drifted out wasn't mechanised music, but a tiny globe of furious pink. It zoomed right up to the tip of her nose, poked a freckle and said loudly, âGosh, you're big, too. You're almost as big as Mama Sinclair!'

âHere,' said Mother, lifting the music box from Isola's slack grasp, âyou've got to wind it . . . Oh, how lovely!'

The mechanism ground out a cog-and-clinkers lullaby â an unfamiliar tune that they all intrinsically knew somehow, as if it had soundtracked their dreams â and a tiny girl with diaphanous wings fluttered round and round Isola's head, inspecting her. Isola watched speechlessly. She'd never seen a creature like it.

âI'll take it inside, Isola, it's too precious,' said Mother as the tinkling refrain repeated. âIt's wonderful, Mama Sinclair.'

The moment she left, Mama Sinclair gave a great boom of laughter, her bosom wobbling generously. âI

knew

it,' she said. âThe look on your face, Isola Wilde! I'm never wrong about these things. You're one o' Nimue's bairn, all right.'

Isola didn't understand the phrasing, but the intent was as plain as the winged girl between her eyes.

âHow . . . How did you â?'

Mama Sinclair tapped her nose. âI've seen 'em gatherin', the Children floatin' in an' out o' your window . . .'

âYou mean the princes?' said Isola, before clamping her hands over her mouth, an involuntary reaction; Father always grew angry when she mentioned them.

âPrinces, you say? You call 'em that? We call 'em Children o' Nimue.'

Isola shifted into a kneel. âChildren of who?'

âNimue! You haven't heard o' Nimue? You live right by her beautiful woodland.'

âBut that's Vivien's Wood.'

âShe's had many names, ol' Nimue.' Mama Sinclair slapped her creaking knee and leaned forward. âNimue and Vivien are one an' the same. The old legends called her the Lady o' the Lake, a creature o' magic an' mystery. Merlin loved her, and Vivien â Nimue â made the ol' wizard teach her all his trickery, and then she lured him to an enchanted forest, and trapped him in an ancient oak tree.'

âIn

that

forest?' Isola pointed to the woodland, eyes wide.

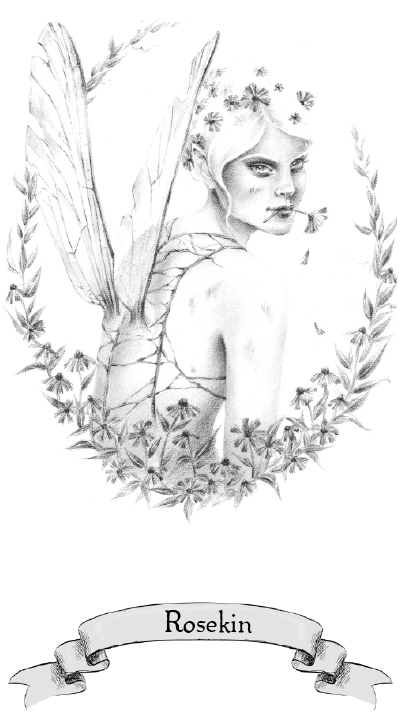

âPerhaps,' said Mama Sinclair, her eyes twinkling. âYou never know. It's said her Children spring from the place where the Lake meets the Tree. Creatures of magic, nevertheless, and they may tell you they're ghosts or fae or pixies or goblins or sirens or what 'ave you. And sometimes, they're people â people like me an' you, pet. This wee Child o' Nimue â' she held out her finger, which the pink bubble alighted upon, resuming its girl-shape ââ is Rosekin. She's o' the fae-kind.'

âFay-kind?'

âA faerie, dear.'

Rosekin curtsied her little leaf-skirt, her pointed features grinning at Isola, her toes and ears and eyes included.

âI like you,' said the faerie loudly. âDo you like me?'

âUm . . . yes.'

âYou have a lovely garden.'

âThanks. My mum â'

âYes,' said Rosekin dreamily, âit looks

so

delicious.' She fluttered off Mama Sinclair's hand and landed on Isola's knee, where she promptly curled up and began biting her own toenails.

âRosekin has kept me company these many years â and I've been keepin' her belly full.' Mama Sinclair chuckled. âBut I'll be goin' soon, an' I thought you could use another â what did you call it? Ah, a

prince

.'

Isola looked nervously down at the grubby faerie girl. Rosekin removed her big toe from her mouth and announced, âI'm hungry.'

âWhat do you eat?'

âMy favourite's honeysuckle.'

Isola looked at Mama Sinclair.

âJust flowers, lass. The prettier the better. She doesn't eat much. Just make sure no-one mistakes her for a pest and sprays poisons!' She got up out of the plastic chair, stretched and paused to watch the dappled shade shifting over her hands for a moment. âBe good, Rosekin, my little pest,' she said, smiling. âAnd happy birthday, Isola Wilde.' She patted Rosekin's tiny head with her fingertip, Isola's head with her hand, and then turned to leave.

âWhere are you going, Mama Sinclair?' Isola called. âI mean, so you can't be with Rosekin anymore?'

The rotund lady from Number Thirty-nine turned back and chuckled. âOh bless, my wee Child o' Nimue â I'm going home!'

Â

Â

A fortnight later Mama Sinclair was buried in the High Cemetery, on a bald hill overlooking the village. She wore her orthopaedic nursing shoes and her Florence Nightingale portrait-pin on her bosom. At her funeral, her husband, the future Boo Radley, spoke at length about her struggle with illness. âThey always call it a battle, a fight against cancer, but my beautiful wife didn't believe in war.' He described her garden, the dirt ingrained in her wrinkles and how she somehow kept flowers blooming year-round. He spoke about her earthy spirituality and her love for animals and children, for hugging and gift-giving, for Vivien's Wood.

In the third pew from the back, Isola thought of her huge squashing breasts and a music box with a secret faerie inside. A human Child of Nimue gone from lake to tree to earth again.

Rosekin was sobbing tiny pink tears in Isola's dress pocket.

Isola had only been to one other funeral before â her grandmother's, when she was four.

âDon't worry,' Mother had said thickly at that occasion, tears trickling over the ridge of her lips as she'd rubbed Isola's back consolingly, âshe died in her sleep.'

Mother had only meant that Grandmother hadn't passed in pain, but that night, Isola had lain awake, too frightened to close her eyes. Her blankets had been drawn up to her chin, and shadows had played puppet theatre on the walls.

âAle,' Isola had said in a Mother-proof whisper, âwhat happens if I die in my sleep?'

The summoned spectre had come when called, but couldn't reassure her that he wouldn't let that happen. Before she could upset herself any further, he'd reached into his breast pocket and withdrew two strange, golden coins.

âTo pay the ferryman,

querida

,' he'd said simply, placing them on her bedside table. âIn case you die in your sleep.'

The funeral had been grand and stoney, with impassive Jesus in the window, his face broken into coloured glass. Grandmother had looked so strange in the casket, her make-up painted far too thickly. Grandmother herself would have sneered and said she looked like one of those

street-corner unfortunates

.

Isola had slipped Father's wallet into the casket before the lid had closed, hoping that paper money would be enough to buy a one-way boat ride.

Mama's Sinclair's funeral was earthy and sweet-smelling, and under their black coats people wore vibrant colours. At the burial, Isola fingered the cool coins in her pocket that Alejandro had given her all those years ago. She hadn't realised, not for years and years, what precious things these were â the last gift from his own small sisters. Isola tossed a snippet of honeysuckle into Mama Sinclair's deep grave, two coins from her own piggybank hidden in the blossom.

Â

Â

Â

Tick Tock

A shriek. A thud in the earth.

â

They're eating my time!

'

Isola shouldered her schoolbag and hurried out the front door. âWhat is it?'

âMy thyme! Those pesky rabbits!' cried Mother Wilde, rubbing her forehead with a gloved hand. âThey'll be into the rosemary next, just you watch.'

She slammed a garden hoe into the dirt again, raging against the creatures that nibbled up her herbs. Isola caught sight of dusty bobtails vanishing into the scrub. One pure black rabbit dived recklessly under the porch of Edgar Allan Poe's new house. She hadn't seen the boy in a while; she left for school much earlier than him, and didn't emerge from the woods until the sky had darkened.

âOoh, those rabbits! I know you love them, Isola, but I swear, if I catch them â' she throttled the air ââ I'll wring their adorable little necks and make adorable bunny soup!'

Isola kissed Mother on her way down the garden path. When she reached the front gate her smile wilted â as the garden did at its edges these days. She was both pleased and despairing to see Mother this way. On one hand, it was wonderful to see her out of the house, working on her long-abandoned project. The unwalled secret garden was not the Eden it once was.

But Isola knew that the manic stage would pass soon enough, and the longer it lasted, the deeper Mother would sink when it ended. Swinging high always meant falling low in the circus of her life. Today, Mother might be the trapeze artist, her sequinned torso glittering in the spotlight, flying high above her illness, but tomorrow she could well be the cockroach crushed under the ringleader's boots, squashed juiceless under the strain of being sad.

Lately in the Wilde house, the swings had become more extreme, a pendulum gathering speed. Soon, Isola feared, the clock would once more stop altogether.

Â

Â

By the time she'd kicked off her shoes in the hallway after school that afternoon, Isola knew that the pendulum had swung.

Yesterday's dishes were stacked high in the sink. The house was unwelcoming, celibate; the kitchen cold with uncooked dinner.

âHow was school, then?' Father asked from the lounge room, his perfunctory question accompanied by the flutter of turning newspaper pages.

âGrape and I faked cramps to get out of P.E.,' said Isola, stopping in the doorway and shrugging at him. âBut Sister K said we used that excuse last week, so I guess the nuns are tracking our periods now.'

From upstairs came the familiar waterfall. The sounds of Mother stripping in the bathroom.

Father turned the television on, pressing the volume control like an addict on a morphine drip. Louder louder louder, the noise shackling Isola's ankles as she trudged her way upstairs. The aural riot tried its hardest to tug her down the stairs, to ignore Mother the way that Father chose to.

Isola allowed her gaze to rise skyward as she peeked through the ceiling with the X-ray vision she wished she had. Perhaps if she stared hard enough she could see through the ceramic tub, through Mother's sun-speckled skin, to find the sadness that roosted in the red stew of her tragic guts, the depression that festered like tumours. She could shrink them with kisses, cut them out with razor-sharp lips like Ruslana's.

It was no secret that Mother was mentally ill. She had only gotten worse since Isola's birth.

Sometimes, very late at night, if she pressed her thumbs into her eyes and concentrated, making pictures in the electric shudders of colour that burst there, Isola remembered being inside Mother's womb. The stucco pink walls were lined with stars, the mapped cosmos; soft gooey blush like the inside of a clam, and she was the grain of sand becoming the pearl.

Mother had other baby pearls brewing before, but instead of hardening they had softened, melting through the porous walls. She took care of these babies too, but nobody knew: she cradled them internally, secretly squished between her organs, padding her ageing joints, collecting in her brain stem. These were seedlings, saplings, never to blossom, never to become trees.

Isola was born to tears spilling from all eyes except hers. She never cried, never made so much as a squeak of befuddlement, and the nurses plunged her airways again and again, looking for the obstruction that didn't exist.

âA quiet little princess you've got, Mrs Wilde,' the nurse said, beaming. Isola was finally planted into Mother's sweat-drenched arms: tiny, wrinkled hands flexing; crusted eyes blue through the gunk; hair like she'd been licked by the unicorns, frothy above her bothered-looking face.

âMy princess,' gasped Mother, flooded with pain-drugs and love-drugs. âMy Isola.'

Isola pushed open the bathroom door to reveal the gentle shafts of chandelier light, inhaling the gel and soap and candle scents.

Her mother was in the claw-footed bathtub, hidden behind the Japanese-print screen, visible in pieces, a triptych; her toes at one end, at the other a twist of dark hair, pinned up. In between was a slinky silhouette, breasts and knees.

Isola went to the porcelain bathtub, kissed Mother's flushed cheek like she always did, dipped her fingers in to check the temperature (usually boiling past most people's endurance), and asked if she needed anything.

âA doctor to double the dosage,' sighed Mother, and then she laughed, lifting her pointed ballerina-foot out of the tub, soapy water dripping and spotting the bath rug. Isola saw her Mother's whole life there â in the corns on her soles; the floaty-violet nail polish, slightly chipped; the dyed string anklet, woven on the shores of some faraway honeymoon beach.

âTell me a story, won't you, Isola?'

It seemed to be one of the few comforting things Isola could administer to Mother; her voice, shaping the clay of a story, a tale that always had a happy ending. Isola didn't think she was much of a storyteller, but she drew inspiration from Lileo Pardieu's words, a vampire drinking in inky blood, and she wove tales until the bathwater ran lukewarm.

Isola loved Mother so much it hurt. The pain only worsened when Mother was hurting. When she was sad, Mother Wilde was a Greek tragedy. She would stay in her bed all day, and got in the bath at odd hours, soaking instead of sleeping, trying in vain to soften the tightly wound cogs inside.

A tealight candle floated past her fingers, and Isola stirred up a wave for it to travel on, a tiny tempest in the tub.

âOnce upon a time,' said Isola quietly, âthere was a boy called Alejandro, who loved his sister very much.'