Faldo/Norman (26 page)

Authors: Andy Farrell

Up in the television tower at the 13th hole was Ken Venturi. The main analyst for CBS, he would call the leaders through the par-five finale to Amen Corner and then hightail it back up the hill to the tower at the 18th for the conclusion of the tournament. No one knew what Norman was going through better than Venturi. In 1956, the 24-year-old amateur, an army veteran from San Francisco, led the Masters for each of the first three rounds and through 16 holes of the final round. He started out

with a four-stroke advantage over Cary Middlecoff but collapsed to an 80.

At the time, the tradition at the Masters was to pair the third-round leader with Byron Nelson, the two-time champion, on the last day. Bobby Jones, the club’s founder, wanted nothing more than an amateur to win his tournament – no amateur had won a major since Johnny Goodman at the 1933 US Open and no amateur has ever won the Masters. But Venturi was Nelson’s protégé, the pair playing exhibitions all round the country, and there was concern that there should be no implication of impropriety. Instead, Venturi was allowed to pick his playing partner and chose Sam Snead, the one member of the great American triumvirate (the others being Nelson and Ben Hogan) that he had never played with. Snead could only look on helplessly as nerves consumed the youngster.

Just before the final round, someone asked Venturi: ‘How does it feel to be the first amateur to win the Masters? You know you’ll make millions.’ Venturi wrote in his book

Getting Up & Down

: ‘I brushed the guy off but the damage was done. He was right. I was going to win the Masters, which was being shown, for the first time, on national television. The victory would change my life. I would become the most celebrated amateur since Jones. I started to get tears in my eyes. With the business offers that were sure to come my way, I would be able to buy my parents new cars or a new house. I suddenly started to think about all the possibilities, when thinking about anything except my game was the last thing I should be doing on the final day of a major championship.’

Venturi three-putted the 1st hole for a bogey but then settled down and another bogey at the 9th still meant he had a five-stroke lead as Middlecoff also struggled on a windy day. But then Venturi bogeyed the 10th, the 11th and the 12th, a run eerily similar to Norman’s. ‘My lead, as well as my sanity, was slipping

away even further. It is difficult even today, almost 50 years later, to describe what it felt like, and what little there was I could do about it. All I can say is that it is the most horrible feeling in the world. I’m sure Greg Norman knows what I mean.’

Venturi parred the 13th but dropped further shots at the 14th and 15th holes, though he still led until he bogeyed the 17th. Jackie Burke had started the final round eight strokes behind and his closing 71 was good enough to claim the green jacket – only Burke and Snead broke par on the day. It remains the greatest comeback in Masters history. Venturi reflected in his autobiography: ‘I know it sounds absurd, but I didn’t really play that poorly. I reached 15 greens in regulation. What killed me were six three-putts, while Burke didn’t register one the whole tournament. I kept hitting the ball on the wrong side of the hole. Did I choke? Well, I suppose if you go by my score, you can make that argument. I chose to look at it differently. The day was tough for everyone.

‘The flight back to San Francisco was the longest of my life. I replayed much of the final round in my head, and it wouldn’t be for the last time. Over the following weeks, months and years, that round would come back to me in the middle of the night, and the result was always the same. I don’t wish that kind of nightmare on anyone.’

Instead of making it big in business and staying as an amateur – he was later informed that had he won, a vice-presidency of the Ford Motor Company would have been his – Venturi turned professional and finished fourth at Augusta in 1958 and second in 1960. He was another player destined never to wear the green jacket, but on a broiling hot day at Congressional in 1964, playing the final two rounds on the same day, Venturi overcame heat exhaustion and dehydration to win the US Open. Injuries ended his career but he overcame a stammer to spend 35 years

broadcasting on golf. He died at the age of 80 in 2013, just months after he was inducted into the World Golf Hall of Fame.

As the 1996 Masters unfolded, Frank Chirkinian, the legendary producer who pioneered the way golf was covered on television, ‘recognising the parallel [with 1956], told everyone to let me run with it, and I did, describing Norman’s frame of mind while everything was falling apart,’ Venturi recalled. ‘For me, it was very tough to watch. Afterward, Norman told me: “You got into my brain.” He seemed surprised. “Greg,” I reminded him, “I’ve been there.” ’

The sensitivity, born of Venturi’s own experiences, shown to Norman on the CBS telecast, was not to everyone’s taste but Chirkinian, a friend of the Australian who was working at the Masters for the last time, had no truck with any critics. ‘There’s no reason to say anything when a television picture is already telling the whole story,’ he told Steve Eubanks. ‘Some members of the print media criticised us for not saying on air that Greg Norman was choking. That really ticked me off. I mean, why say it? The viewers could see for themselves what was happening. It’s obtuse.’

Hole 14

Yards 405; Par 4

A

FTER MOVING

away from the 13th green and, usually, its stunning backdrop of azaleas, the course turns back on itself for the 14th hole, Chinese Fir. It was Louis Alphonse Berckmans, a member of the Beautification Committee, who named the holes in 1932, working with Bobby Jones and Clifford Roberts. The committee had suggested ‘concentrating in the vicinity of each hole a massed profusion of a distinctive variety of trees or plants that bloom during the winter season’. Remember, the course was intended only to operate in the winter.

Berckmans was 74 years old and no golfer but he became a member of the club and his younger brother, Prosper Jr, was the club’s first general manager. Their grandfather, the Belgian Baron Louis Mathieu Edouard Berckmans, bought the old indigo plantation in 1857 and turned it into the Fruitland Nurseries, which imported plants and trees from various countries. Their father, Prosper Julius Alphonse Berckmans, who helped to popularise the azalea, continued the nursery until his death in 1910 and a few years later it ceased operation.

But many prominent features remain today, such as the azaleas and the long row of magnolias that guards the drive up to the

clubhouse, known as Magnolia Lane. The clubhouse, which was built in 1854 and became the baron’s home, was the first cement house constructed in the American South, while outside it is the country’s first, and still the largest, wisteria vine. A big oak tree that stands next to the clubhouse on the golf course side also dates from the 1850s; it is here that people are referring to when they arrange to ‘meet under the tree’.

Various pine trees dot the property, loblollies being the most common, with some more than 150 years old (particularly down the 10th) and others dating from the 1930s when the course was built, although more have been added in the last decade. A few of the plants after which the holes are named were already in place but most were planted specially. The Masters Media Guide estimates that more than 80,000 plants of over 350 varieties have been added to the course since it opened.

All of which goes to show that a hole without water, or even a bunker, such as the 14th, can still be visually stunning – and awfully difficult to play. Since 1952, when a bunker to the right of the fairway but not especially far from the tee was taken out as it only inconvenienced some of the older members, it has been the only hole on the course without sand, although the 5th, 7th, 15th and 17th holes started life without bunkers when the course was built. It is the contours on the green that make the 14th such a tricky proposition and where the hole is positioned makes a difference all the way back to the tee shot.

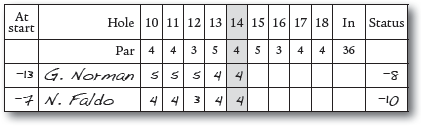

Still leading by two strokes, after the final pairing’s first ‘half’ for six holes, Nick Faldo had the honour at the 14th and drove down the right side of the fairway, only to see his ball catch a slope and run down to the trees on the edge of the fairway.

Greg Norman hit a three-wood down the left side of the fairway, seemingly in better shape. But the pin was on the top left shelf of a green that essentially sweeps down in tiers from left to

right, as well as containing a myriad of other slopes. Norman had to land his approach well up the left-hand side of the green but it pitched sufficiently short and right of the pin that it caught the slopes and ran down to the third of the tiers on the right-hand side of the green, leaving a monster putt. These were the very same slopes which helped him out on Thursday when the hole was on the right-hand side of the green but now each roll of the ball took it further from the target.

The 14th hole is a very gentle dogleg from right to left, not nearly as pronounced as the 2nd or the 13th, for example. Since a number of holes are shaped in this direction, Masters lore maintains that a right-hander who draws the ball (or a lefty who favours a fade) has an advantage at Augusta. As usual in these parts, it is a little more complicated than that. Few courses demand such an array of shots, fades and draws, with virtually every club in the bag.

In

The Making of the Masters

, David Owen refutes the theory that the right-to-left hitters have an inbuilt advantage. ‘Although it is true that several holes on the course have fairways that bend to the left and therefore seemingly favour players who can draw the ball off the tee – the 2nd, 5th, 10th, 13th and 14th holes immediately come to mind – the matter is not so simple as it may at first appear. (And it doesn’t help to explain the Masters success of Hogan, Nicklaus, Faldo and Woods, to name four notable faders.) One usually overlooked fact about Augusta National is that all of its notable right-to-left holes, including the 14th, have wide-open landing areas on the right but severely punish shots that are hit too far to the left.’

Take the 13th: how many players have overdone the draw off the tee and ended up hooking into the creek on the left of the fairway, or over it into the trees? Ian Woosnam was over there in 1991 but managed to make a bogey and went on to win. Others

have not been so lucky. Such mistakes, according to Owen, ‘violate a cherished piece of local knowledge: play away from the doglegs. On all the holes that seemingly favour players who can work the ball to the left, the only sure way to get into hopeless trouble off the tee is to hit a hook.’ He adds: ‘On holes where draws are seemingly favoured from the tee, the greens often demand approach shots that move in the opposite direction.’

A high fade is usually the best way of softly landing a shot onto the (usually) rock-hard greens. Faldo would spend weeks before the Masters practising his high shots and utilising them in the tournaments on the run-in to Augusta.

It depends, however, on where the flagstick is and with the back-left pin position on the 14th, getting close with any sort of shot is extremely difficult. Norman was just left of centre of the fairway with his tee shot and could not manage to get his approach close. Faldo’s aim had been to open up the green by finishing in the right half of the fairway. And, as local knowledge avers, erring away from the dogleg does not lead to severe punishment. In fact, despite a tree a little way in front of him to the left, Faldo had a perfectly clear line to the green and safely found the heart of it, the contours again rejecting his ball from the top tier but leaving it on the middle plateau, 30 feet from the hole.

Norman faced a putt from more than 80 feet, up, down, and up again, and it was a brilliant effort. He got the pace almost exactly right and the ball came up six inches short and to the right of the hole. He tapped in for his first par since the 7th. Faldo, although from under half the distance, could not quite find the same touch and his lag putt came up three feet short. Still work to do, but he popped it in to maintain his two-stroke advantage.