Faldo/Norman (24 page)

Authors: Andy Farrell

In 1990 in the final round, Faldo went into the back left bunker and had a plugged lie. He got his second shot just over the lip and kept it from going into the creek but he still had to make a 15-footer up a slope from just off the green to save his par. It was an important moment in the round, allowing him to charge to the top of the leaderboard over the last six holes and get into a playoff. He was playing that day with Nicklaus. They had not exchanged a word until that point. Faldo said: ‘Thank God we don’t have to play that hole every week.’ Nicklaus replied: ‘Hell, I’ve been playing it for the last 35 years.’ Faldo, cheekily: ‘That’s older than me, Jack.’ No further response from Nicklaus.

Six years later, Nicklaus was playing the final round well ahead of the leaders. In the group just ahead of him, Fred Funk had hit his tee shot at the 12th over the green into the bunker back left. As Funk prepared to play his next shot he discovered a two-foot-long snake in the sand. He looked towards a rules

official for some help but was told to play on. It is well known that Nicklaus does not like snakes. Before their playoff for the US Open at Merion in 1970, Lee Trevino produced a rubber snake from his bag and threw it across the tee, frightening the life out of the Bear. Nicklaus now hit his tee shot at the 12th into the same bunker with the snake in it and, as he walked towards the green, rules officials from both the 11th and 12th greens managed to persuade the snake to disappear into the woods behind the green.

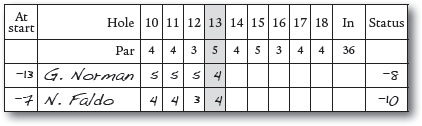

Faldo had pars at the hole on the first two days and then dropped a shot in the third round when he went over the green. On the first day, no balls at all went in the water. On the Friday, the 12th was the hardest hole on the course. It all depends on the pin position and the wind. Norman birdied the hole on Thursday and did a Fred Couples on the Friday when his ball stayed up on the bank and he chipped close to save par. On Saturday he found the water and then dropped in a position that gave him a third shot from around 80 yards and he managed to get up and down for a bogey four.

On Sunday, just when he needed something positive to go in his favour, Norman had found the water again. Once more he dropped in a position to give himself a shot from around 80 yards as he had the previous day. He hit a good third shot, but not the great one he needed, leaving himself a 12-footer for bogey. Faldo putted first from 15 feet for a birdie and stroked it a foot past the hole, a confident putt that only just missed on the left, and he then tapped in for his par. Norman, again taking an age over the ball, never got the ball running at the hole. It finished just short and below the hole and he tapped in for a double bogey five.

Extraordinarily, Norman had taken a five at each of the last five holes: par, bogey, bogey, bogey, double bogey. Over those five holes Faldo had made up six strokes with nothing more than a

birdie at the 8th followed by four pars. He had gone from four behind to two ahead. Had it indeed been matchplay that afternoon they would have now shaken hands on a 7 and 6 victory to Faldo. Eight strokes had been exchanged in 12 holes and now Norman trailed for the first time since early on Thursday.

Faldo, still at nine under par, led by two from Norman at seven under, with Frank Nobilo and Phil Mickelson at five under par after 15 and 13 holes respectively. After a bogey at the 12th, Mickelson birdied the 13th from the pine straw right of the fairway, not quite the stunner he hit 14 years later from an even trickier spot but another sign of his willingness to go for broke. At four under par were Duffy Waldorf and Scott Hoch, while Davis Love had the clubhouse lead on three under.

Until then, the largest lead lost at the Masters was the five-stroke advantage Ed Snead relinquished in 1979. The 34-year-old three-time tour winner was five ahead of Watson and Craig Stadler with a round to play and was still three ahead with three to play. But he bogeyed each of the 16th, the 17th and the 18th, where he missed a three-footer for the victory. He shot a 76 and ended up in a playoff with Watson and Zoeller. All three parred the 10th hole but Zoeller won with a birdie at the 11th. This was the only time Snead contended at Augusta, and afterwards he only won once more in his career.

For Norman, his latest collapse had become a long-drawn-out, gut-wrenching affair. By now he was six over par for the day and in danger of not breaking 80. ‘I just told myself it’s not over,’ he said. ‘I was two back and I said you can finish with straight birdies. A good run to the barn is what I said to myself in my head. I never gave up belief that I could win the tournament. But Nick played great golf the last six holes. Very, very solid.’

Was Norman still thinking straight? To his credit, a couple of birdies did arrive in the next few holes but it was Faldo’s

summation of the situation that hit the mark. He said that night: ‘It’s excessive pressure. It’s the highest degree of accuracy of any golf course. It’s the most strategic-thinking golf course in the world. You know what it’s like, how they set it up. As the week goes on and the screws get tighter, it’s a very tough golf course. That’s what makes it tough.’

What Faldo said to his caddie Fanny Sunesson as they walked back to the 13th tee was: ‘Bloody hell, now it’s mine to lose.’

Hole 13

Yards 485; Par 5

A

S HE PREPARED

to tee off at the 13th hole, Nick Faldo looked anything but machine-like. He was a whirl of motion, or at least of slow and soft movements, not fidgety exactly, just loose. He took his glove out of his pocket, rubbed his nose, put the glove on his left hand and took his driver out of the bag. He placed his ball on a tee in the ground and took two steps back, wiped his left hand down the left side of his shirt, then stretched each arm in the air one after the other.

He took two practice swings, the first just the backswing and the downswing, arriving back at the address position, then a complete swing all the way to the top of the follow-through. Then he took another step back and briefly rested the grip of his driver on his thigh while he spread the fingers of each hand. As he walked forward towards the tee markers and his ball, he transferred the club from his left hand to his right, then back to his left hand. He placed the clubhead behind the ball and gave it a waggle. Then he spread his feet into his stance. Backwards and forwards he shifted his weight from one foot to the other.

And then he hit the ball. The process took almost exactly a minute and at no point was he completely still, at no point could

tension be allowed to creep into his body. Faldo was now leading the 60th Masters by two strokes from Greg Norman. He did not actually hit the best of drives at this always-critical par-five. It finished just on the edge of the fairway up by the copse of trees on the right, but not in them. Not ideal but fine in the circumstances. This is how Faldo had learnt to feel the pressure and still be able to cope. Faldo the golfer was no robot.

Yet he often was labelled a machine after having parred all 18 holes to win the Open Championship at Muirfield in 1987. Further proof seemed evident in the mechanical way he had spent two years completely dismantling his swing and putting it back together again.

Sports science was in its infancy in Faldo’s heyday but he was at the forefront of it. He was prepared to work tirelessly with his coach, David Leadbetter, to understand which bits of his action worked and which did not and needed upgrading (pretty much all was in the latter category). But he was also aware of the need to attend to fitness, nutrition and psychology, although the last he only admitted years later when it had become fashionable rather than a reason to be laughed off the fairways. The week before the 1996 Masters his eyes underwent electrical stimulation massage from American eye specialist Craig Farnsworth, so it was no surprise to him that he was near the top of the putting statistics for the week.

What Faldo never lost sight of, however, was the passion needed to endure and ultimately conquer. All the vital preparation was only a prelude to hitting the right shot at the moment it mattered most. On the 18th hole at Muirfield in 1987, he had 190 yards to the green and thought about hitting a soft four-iron, as the yardage suggested and logic demanded, and instead, taking into account the adrenalin of the situation, went for a hard five-iron.

This is no machine talking: ‘You can’t imagine what it is like to try and play in those conditions. It’s like those heart-stopping moments when you think you’re going to be involved in a car crash. You go all hot and cold. It’s such an important moment and yet it’s over in seconds. I had to hit the shot and I didn’t know if I could – but I knew it had to be done. Then, suddenly, there it was flying straight at the green and all I could think was, “Cor, look at that.” ’

He probably should have hit the four-iron since his approach finished on the front of the green, 40 feet from the hole. He putted up pin-high but five feet wide of the cup. He knew he had to hole the putt to win his first major championship. And he did. But he was not the champion until Paul Azinger, the overnight leader playing in the pairing behind Faldo, had bogeyed the 18th hole. The American had led by three strokes at the turn but came home in four over, bogeying the 17th hole as well as the last. Not for the last time, Faldo had won by avoiding mistakes when others could not do so.

In

Beyond the Fairways

, David Davies wrote of Faldo’s 18 successive pars that: ‘It led to him being labelled “machine-like” and “boring”, yet nothing could have been further from the truth. Some of Faldo’s pars were as exciting as any eagle, given the strain of the occasion. At the 8th, he was in a bunker some 30 yards from the green and hit it to four feet, to save his four. His huge sigh of relief was echoed later when he described that moment as crucial.’

‘I was trying to make birdies,’ Faldo told

Golf World

in 2002. ‘Everyone makes a big thing of the 18 straight pars, and it used to irritate me a bit when people said I was boring because I churned out all those pars. If it had been four bogeys and four birdies, they would have described it as extraordinarily exciting. I was trying to birdie every hole, but I was nervous. I hadn’t won a major before, the weather was like pea soup all week, and I wasn’t putting great.’

It did not help that Faldo went into a ‘cocoon’, as he described it. He found a switch to shut everyone and everything else out, but that meant in terms of watchability he was some way behind the charisma of Seve Ballesteros, the showmanship of Norman, the casual effortlessness of Sandy Lyle, the pugnacity of Ian Woosnam. Even the Teutonic efficiency of Bernhard Langer had its own charm. But there always seemed to be a barrier between Faldo and his fans. ‘Walking down the 14th,’ Faldo wrote in

Life Swings

of the 1987 final round, ‘everything became a blur; I could no longer hear the encouraging voices in the gallery, I was no longer aware of my surroundings, I was cocooned in a little world of my own. I could see my shoes and each footstep, but beyond that, nothing. In modern parlance, I was “in the zone”.’

The better Faldo became, winning more by making fewer mistakes, the worse it got. By 1990 he was the most dominant player in the world but Peter Dobereiner, in a tongue-in-cheek column for

Golf Digest

that year, pointed out there was a conflict between his twin ambitions to win every major – he had won the Masters and the Open at St Andrews that year as well as just missing out on a playoff at the US Open – and inspiring people to fall in love with the game. ‘My advice,’ Dobereiner wrote, ‘is that you perfect your recovery shots. Then, once you have the situation well under control, you can enjoy yourself by devising private challenges. “What if I were to pull-hook a drive onto that tiny island in the middle of the lake and then blast a three-wood over the trees onto the green?” That sort of thing. That would do a world of good both for you and your golf. After all, nobody loves a machine and nobody would want to take up a game that a machine can play better than a human.’

Hopefully, we are a long way off the time when a machine can play golf better than a human but perhaps we found out when Tiger Woods was at his peak in 2000–01 that making the game

look too easy, or too much of a foregone conclusion, makes it more difficult to hold people’s attention. There is the man in heaven in

A History of the World in 10½ Chapters,

by Julian Barnes, who takes up golf, starts getting better, but eventually gives up the game when he goes round the celestial course in only 18 strokes. It is the earthly, human element of players overcoming adversity that makes golf interesting.

Faldo demonstrated this at Muirfield in 1992, when he almost threw away a third Open crown. He had played sublime golf all week, almost faultless, especially during a second round of 64. ‘It was a unique feel,’ he said. ‘I felt comfortable over everything, whatever club was in my hand. I have been trying to lessen my perfectionist tendencies. I learned this winter not to be hard on myself and realise you could hit bad shots. I am not worried about the clinically perfect round of golf. I enjoyed today because on every shot I set myself a target and nearly always got it.’ The last day however was a different story. Faldo started with a four-stroke lead, but after 14 holes he had not made a birdie, which would have been reminiscent of five years earlier had he not had four bogeys. John Cook, playing ahead of Faldo, birdied the 15th and 16th holes to take the lead by two. Fortunately, it was at times like this that Faldo became inspired. At the 15th, he told himself: ‘I have to forget about the whole week and play the best four holes of my life.’