Far North

Authors: Will Hobbs

Will Hobbs

to the Dene of today and tomorrow

THE FIRST I EVER heard of the Nahanni River andâ¦

THE WIND BLEW COLD off the Great Slave Lake, evenâ¦

I THOUGHT WE'D HIT it off real well, but theâ¦

WITH DAYLIGHT FALLING off by more than ten minutes aâ¦

RAYMOND'S EYES TOOK in a glimpse of me, and thenâ¦

“THIS IS CESSNA 6â7-Z-RAY calling Fort Simpson. Do you read?

CLINT TRIED TO RESTART the engine. “Charge on the battery'sâ¦

THE OLD MAN ALREADY had a fire going. It broughtâ¦

IN THE MORNING Johnny Raven built a larger fire outsideâ¦

WE WASTED NO MORE time talking; we never even agreedâ¦

IT HAD BEEN ALL we could do to get theâ¦

THE OLD MAN STOOD on the top of the bank,â¦

A HALF-CHINOOK SWEPT briefly into the valley, raising the temperatureâ¦

“âMY NAME IS Mary Canadien,'” Raymond read aloud. “âI amâ¦

WE STAYED INSIDE the cabin the next day. I wasâ¦

IT WAS ONE HUNDRED and ten degrees warmer inside theâ¦

THE RAM WAS STANDING amid the skulls and skeletons ofâ¦

A RAVEN SHOWED UP within minutes, then two, three, fourâ¦

“WINTER BEAR,” RAYMOND said, his voice hushed and awed. Theâ¦

AT LAST THE FIRE in the stove was backing offâ¦

DON'T THINK ABOUT how far a hundred miles is, Iâ¦

MY FATHER AND I flew upstream over the frozen Liardâ¦

Â

T

HE FIRST

I

EVER

heard of the Nahanni River and Deadmen Valley was from the bush pilot who met my flight at Fort Nelson, way up at the top of British Columbia. Clint worked for an air charter service that was trading out a favor for my father by flying me on to Yellowknife, the capital of Canada's Northwest Territories.

“Gabe Rogers?” he asked doubtfully as I stepped off the plane.

“Clint?” I asked just as doubtfully. “You're the bush pilot?”

This guy was about twenty-two, that's the oldest I'd give him. Big grin, friendly as a puppy dog, big head of curly blond hair, and a square jaw with a dimple in it. He said, “You talk just like your dadâTexas accent and all. I was expecting you to be tall like your dad, too, eh?”

“Nobody's as tall as my dad,” I said. “That's why they call him Tree.”

A mischievous grin spread across the young bush pilot's face. “Anybody ever call you Stump?”

I had to laugh. “Not until now, but there's a first time for everything.”

“I've seen some big guys on those drilling rigs, but nothing like your dad, eh? Your shoulders sure remind me of hisâwide as an ax handle. You wrestle?”

“Wrestle and play football. I was a running back.”

“Hockey's my gameâyou ought to try it. Hey, guess what. Another pilot took off with my airplaneâthere's a forest fire going on north of here, up in the Yukon.”

“So how do we get to Yellowknife?”

“Well, the company's got a van stuck here at Fort Nelson, and now they figure I'm just the guy to drive it back to Yellowknife.”

“How far's that?”

“Oh, only about six hundred miles.”

We piled my gear into the van, an old Suburban armored with red dirt and a windshield that looked like it had been through a war. On a wide gravel road that stretched endlessly ahead through a forest of shaggy spruce trees, Clint

buried the gas pedal, leaving behind a contrail of dust. It looked as if he intended to drive to Yellowknife in the same time it would have taken to fly there. I glanced nervously at the speedometer. He was already doing 115 kilometers per hour, whatever that was. It sure felt fast on the gravel, and I started to wonder if this guy was going to kill me, but I didn't say anything. I tried to relax, figuring that was just the way people drove in Canada.

“This road didn't even exist ten years ago,” Clint said with pride. “The first thing you should know about the Northwest Territories is that it's

big.

It stretches from the Yukon practically to within spitting distance of Greenland. The N.W.T. is twice as big as Alaska.”

In that case, I thought, Texans have absolutely no bragging rights in the North. “That's big,” I agreed, as my eye went back to the speedometer. He was up to 125 kilometers per hour.

“See if you can picture this: only sixty thousand people live in the entire N.W.T., and almost a third of them live in the city of Yellowknife.”

I was taking in the scale of one tiny corner of it in the green blur rushing by the passenger window, the big emptiness and the strangeness. For a kid from the Texas hill country, this world

of the northern forest seemed like something you'd read about in a book and wonder if it could possibly be real. I felt good about my decision to come try it. It might be rugged up here, but I could already tell it wasn't going to be boring.

Clint was steering left-handed down a long straightaway with only a couple of fingers on the wheel, while his right hand was fiddling with a yellow fishing jig in a tackle box between us. A hundred and forty kilometers per hour, that's what the speedometer was reading now. The van didn't feel very attached to the gravel. It felt more like we were floating. Back in Texas, my grandparents drove so slow it made me crazy. That wasn't a problem with Clint. “So how does kilometers per hour compare to miles per hour?” I asked him as casually as possible.

“Ten kilometers is right around six miles.”

I did the math in my head. The answer scared me, so I did it over. I was right the first time: eighty-four miles an hour. To get my mind off Clint's driving, I asked, “What's the deal with the trees turning gold and red already? It's still August.”

“Those are aspens and paper birch. Another eight or nine weeks, and the hammer comes down.”

“The hammer?”

“Winter! Welcome to the Northwest Territories!”

“What's that mean, âhammer'?”

“Sledgehammer!” He laughed. “The cold and the darkness, that's the hammer, and the land, that's the anvil. There's practically three hours less daylight now than there was a month ago.”

“Too bad I missed summer.”

“So you're starting school in Yellowknife?”

“Tenth grade.”

“From what I hear, those residential schools are no picnic.”

“I'll make out all right. I wanted to be closer to my father.”

“While he's working the diamond boom and making the big bucks, eh? Your mother's back in Texas?”

“I've been living with my grandparents in San Antonio while my dad's been up here. My mother's dead.”

“I didn't know. I'm sorry.”

“I was only seven. Car wreckâdrunk driver.”

For a couple of minutes Clint didn't speak. Maybe he slowed down a little. Then he pointed off to our left. “That's the southern edge of the Mackenzie Mountains. Ever hear of 'em?”

“All I know about Canada I learned in the old Bullwinkle cartoons.”

“That's the way of it, eh? We Canucks know you, but you Americans, all you think of when you think of Canada is moose, right?”

“I guess so,” I agreed.

“Well then,” Clint said thoughtfully, “just for the sake of argument, let's say all of Canada is one big old moose. Then, what you Americans really know about us, that would compare to about the size ofâ¦a moose dropping.”

“Interesting way to put it,” I said. I was trying to visualize a moose dropping, having never seen one before.

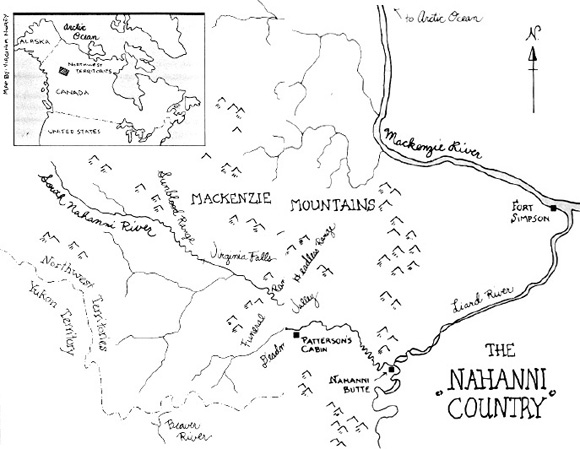

“Anyway, I was going to tell you about the Mackenzie Mountains. In July I flew a couple of canoe parties back in there. They were going to paddle out of the mountains on the South Nahanni River.”

“Did they make it?” I joked.

“Hey, no guaranteesâ¦. It's sometimes called the River of Mystery for all the strange things that have happened back there. And everything's huge. The Nahanni's got a waterfall on it twice as high as Niagaraâ”

“You're pulling my leg.”

“Dead serious. They call it Virginia Falls. The whole river takes a three-hundred-eighty-five-foot drop. It's quite a sight. Below the falls the

river's running in a deep canyon, like your Grand Canyon.”

“That sure would be something to see.”

“There's a lot of history back in thereâhistory and legends. The Nahanni country took a lot of lives when some of the Klondikers tried it as a shortcut to the goldfields over in the Yukon back in 1898. In 1908 a pair of brothers turned up dead up the Nahanniâminus their heads. According to the legend, the native people who lived back in thereâthe head-hunting Nahaniesâhad a white European queen. Their stronghold was a tropical valley complete with palm trees that grew right out of the permafrost.”

“Sounds like great material for a movie.”

“According to the story, there were even dinosaurs back in there that lived around some steaming hot pools.”

“That's even better.” I laughed. “Sounds like Texans have nothing on Canadians when it comes to tall tales.”

“The place where the headless prospectors were found came to be known as the Valley of Vanishing Men and then Headless Valley and finally Deadmen Valley. That was just the beginning of it. There've been lots of strange deaths and disappearances since then.”

“So what's your theory about those guys' heads?”

Clint put his finger to his dimple, then stroked his chin thoughtfully. “I figure they starved to death back in there, in late winter or spring. Bears have an uncanny sense of smell, and they come out of hibernation looking for winterkill. It's easy enough to picture bears knocking the heads loose from those skeletons, trying to get at the brains inside. After that, the skulls washed into the river or wolves carried 'em off.”

“You paint a pretty picture, Clint.”

“Listen to some of these names: the Sombre Mountains, the Funeral Range, the Headless Range, Crash Lake, Hellroaring Creek, Sunblood Mountain⦔

“Sounds like maybe you should stay out of there.”

A grin played at his lips. “Bush pilots have a saying: âI wish I knew where I was going to die, for I would never go near the place.'”

Two months later, Clint would be deadâon the Nahanni. And I would watch it happen.