Farlander

Authors: Col Buchanan

The son breathes, the father lives.

ONO, THE GREAT FOOL

EIGHTEEN: The Sisters of Loss and Longing

TWENTY-TWO: Fishing With Pebbles

TWENTY-FOUR: Waiting by Mokabi

TWENTY-SEVEN: A Day for Rejoicing

TWENTY-NINE: A Storm in the Mountains

PROLOGUE

Ash was half dead from exposure when they dragged him into the hall of the ice fortress and threw him at the feet of their king, where he landed on the furs with a grunt of surprise, his body shaking and wanting only to curl itself around the feeble heat of its heart, his panting breaths studding the air with mist.

He had been stripped of his furs, so that he lay in underclothing frozen into stiff corrugations of wool. His blade had been taken from him. He was alone. Still, it was as though some wild animal had been thrown into their midst. The villagers hollered amid the smoky air, and armed tribesmen jabbered for courage as they prodded at his sides with bone-tipped spears, hopping and circling with caution. They peered through the steam that rose off the stranger like smoke; his breath spreading in clouds across the matted surface of lice-ridden skins. Through gaps in these exhalations, droplets of moisture could be seen running down his frosted skull, past ice-chips of eyebrows and the creased-up eyes, dripping free from sharp cheek bones and nose and a frozen wedge of beard. Beneath the thawing ice on his features, his skin looked black as night water.

The shouts of alarm rose in volume, until it seemed the frightened natives would finish him there and then on the floor.

‘

Brushka

,’ growled the king, from his throne of bones. His voice rumbled from deep within his chest, echoing around the columns of ice arrayed along the length of the room, and rebounding back at him from the high-domed ceiling. At the entrance, tribesmen began to shove the wide-eyed villagers back through the hangings that veiled the archway. They resisted at first, voicing their complaints; they had been drawn there in the wake of this old foreigner who had staggered in from the storm, and felt compelled to see what would happen to him next.

Ash was oblivious to it all. Even the occasional jab of a spear failed to draw his attention. It was the sensation of nearby heat that roused him at last, causing him to lift his head from the floor. A copper brazier stood nearby, with bones and cakes of animal fat smoking and burning in its innards.

He began to crawl towards the heat, as clubbing spears tried to deter him. The blows continued as he huddled against the brazier’s warmth and, though he flinched under every blow, he refused to move from it.

‘

Ak ak!

’ barked the king, and his command finally forced the warriors to draw back.

A silence settled in the hall, save for the snapping flames and the tribesmen’s heavy breathing as though they had just returned from a long run. Then, through it all, a groan of relief sounded loud and clear from Ash’s throat.

I still live

, he thought with some wonder, in something of a delirium, as the glow of the brazier seared through him. He clenched numb hands into fists to better feel the precious heat held within them. He felt the skin of his palms begin to sting.

At last, he looked up to take in his situation. All around he saw the gleam of grease on bare skin, blankets worn like ponchos over bodies half-starved in appearance, faces pierced with bone, gaunt and hungry-eyed; a little desperate.

He counted nine armed men in all. Behind them, the king waited.

Ash gathered himself, though he doubted he could manage to stand just then. Instead, he shuffled on to his knees, to face the man he had ventured all this way to find.

The king studied him as though considering which part to devour first. His eyes were like flints nearly lost in the fleshiness of his face, for he was a huge man, so grossly inflated with fat that he required a girdle of stiffened leather slung across his lap to support the sag of his belly. Otherwise he sat there almost naked, his skin agleam with a thickly applied layer of grease, with only a necklace of leather hung against his chest, and his feet bound in a massive pair of spotted-fur boots.

The king took a drink from an upturned human skull, and smacked his lips in leisurely appreciation. A belch erupted from his gullet, the flab of his neck quivering, then he produced a long, self-satisfied fart that quickly polluted the smoky air with its tang. Ash remained silent and unperturbed. It seemed that all his long life he had been confronting men like this: petty chiefs and Beggar Kings, once even a self-proclaimed god: figures who sometimes hid behind the glamour of status, or even a semblance of polite gentility, but remained monsters all the same – as was this man before him, and as all self-made rulers must be.

‘

Stobay, chem ya nochi?

’ the king asked of Ash, his gaze moving over him with a ponderous intelligence.

Ash coughed life back into his throat. His dry lips cracked open and he tasted blood on them. He stroked his neck in a gesture of need.

‘Water,’ he finally managed.

A royal nod. A water sack landed at his feet.

For a long time, Ash drank greedily from it. Then he gasped, wiped his mouth dry, leaving a smear of red on the back of his hand.

‘I do not speak your language,’ he began. ‘If you wish to question me, you must do so in Trade.’

‘

Bhattat!

’

Ash inclined his head, though he did not respond.

A frown creased the king’s face, muscles trembling as he barked an order to his men. One of the warriors, the tallest, strode to one side of the great chamber, where a box sat by the wall of carved ice. It was a simple wooden chest, the kind used by merchants to transport chee or spices. All eyes in the hall looked on in silence as the warrior unbuckled a leather latch and wrenched open the lid.

He stooped and grabbed something up in both hands. Without effort he pulled it out – a living skeleton still clad in flesh and tattered clothing. Its hair and beard were overgrown and matted, and it peered about with red-rimmed eyes that squinted against the light.

Bile surged in Ash’s gut. It had never occurred to him there might still be survivors from last year’s expedition.

He heard the grinding of his back teeth.

No. Do not become attached

to this.

The tribesman held the starving man upright, until his stick-like legs had stopped shaking enough to support his weight. Together, slowly, they approached the throne. The captive was a northerner: one of those desert Alhazii, judging from what grim looks were left to him.

‘

Ya groshka bhattat! Vasheda ty savonya nochi

,’ the king ordered, addressing the Alhazii.

The desert man blinked. His complexion, once swarthy like all his people, was now as yellow as old parchment. By his side, the tribesman nudged him until his gaze came to rest on Ash. At that his eyes brightened, and some flicker of life returned to them.

He opened his mouth with a dry clucking noise. ‘The king . . . would have you speak, dark face,’ he rasped in Trade. ‘How did you come to this place?’

Ash could see no reason to lie, just yet.

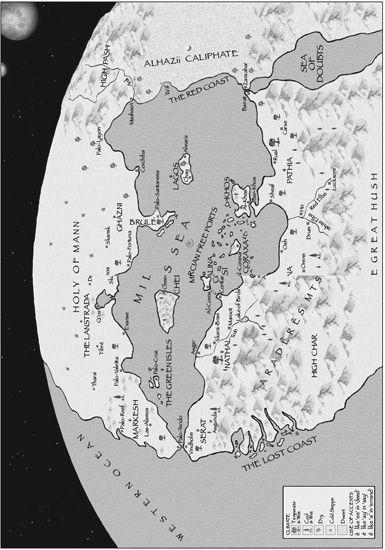

‘By ship,’ he said, ‘from the Heart of the World. It still waits for me now on the coast.’

The Alhazii recited this information to the king in the tribe’s own harsh tongue.

The king waved a hand. ‘

Tul kuvesha. Ya shizn al khat?

’

‘From there,’ translated the Alhazii. ‘Who helped you to come from there?’

‘No one. I hired a sled and dog team. They were lost in a crevasse, along with my equipment. After that, I was caught in the storm.’

‘

Dan choto, pash ta ya neplocho dan?

’

‘Then tell me,’ came the translation, ‘what is it you will take from me?’

Ash narrowed his eyes. ‘What do you mean?’

‘Pash tak dan? Ya tul krashyavi.’

‘What do I mean? You come here from a long way.’

‘Ya bulsvidanya, sach anay namosti. Ya vis preznat

.’

‘You are a northerner, from beyond the Great Hush. You come here for a reason.’

‘Ya vis neplocho dan

.’

‘You come here to take something from me.’

The king jabbed a sausage-sized thumb at one of his sagging breasts. ‘

Vir pashak!

’ he spat.

‘That is what I mean.’

Ash might have been a rock carved in the perfect likeness of a man, for all the reaction he now gave to the question hanging between them. A frigid gust whistled in from outside, flapping the heavy furs draped across the entrance archway behind him, causing the flames of the brazier to recoil. The storm reminding him of its existence, and that it was waiting for his return. For a moment – though only for a moment – he wondered if perhaps now was the right time to introduce a few choice lies. It was not in Ash’s nature to ponder overly long on matters of consequence. He was a follower of Dao – as were all R shun – therefore better to remain calm and act spontaneously, guided by his Cha.

shun – therefore better to remain calm and act spontaneously, guided by his Cha.