Fierce (7 page)

Authors: Kelly Osbourne

I think my mum banned him, not the school. They probably thought he was funny. Everyone else bloody did. In the end, my mum used to go by herself. I wasn’t bothered that my dad didn’t go to parents’ evenings. It meant that everyone wouldn’t be talking about it at school the next day. ‘Did you hear what Kelly’s dad did last

night?’ All that sort of shit.

My dad hated school and I felt the same when I hit my teens and moved to America. I’m incredibly proud of my dad and what he’s achieved on his own merits without an education. Of course, getting an education is vitally important. But I think I realised at an early age that I would be one of those people who learned outside the classroom. I would get a different type of education.

It was blatantly obvious that I had a good grasp of what drugs were. I was blatantly way more knowledgeable on the subject than my innocent school friends.

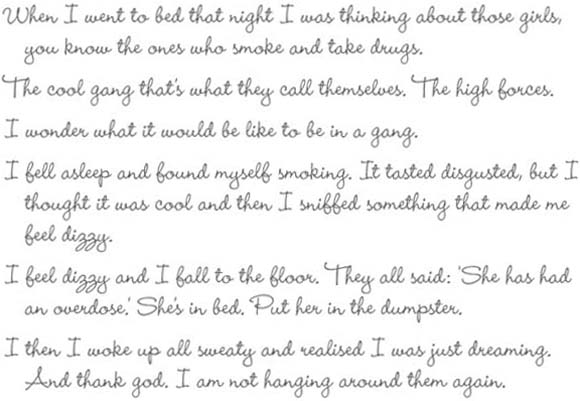

Once, in English, we had to write about the dream we’d had the night before. Thinking about it, what if you’d not had a dream the night before? The teacher didn’t consider that. And you can’t always remember them, can you? I wrote the following (I’m writing about a dream within a dream):

Books and events

Dyslexia: How to Survive and Succeed at Work

by Sylvia Moody, Vermillion, £9.99, ISBN 978-0091907082 This is a brilliant book for dyslexics who have problems at work, such as with reading, writing organisation, time management and remembering things.

Dyslexia: A Teenager’s Guide

by Sylvia Moody, Vermillion, £9.99, ISBN 978-0091900014 This offers tips on reading, writing, spelling, remembering things, taking notes, studying and dealing with exams.

To celebrate Dyslexia Week, the British Dyslexia Association has launched a Wake Up 2 Dyslexia national campaign which runs for a month each year. The main aim is to raise money and awareness about dyslexia. Get in touch via the the British Dyslexia Association for more information.

‘My Dream’

Where the fuck did I get that shit from? Now I can’t even remember writing it. I’m actually shocked. I was twelve years old. It must have come from knowing about my dad. It was obviously something that was on my mind.

Similarly, when I read the book

Junk

for the first time, I knew what everything meant. No one else at my school had a clue.

Junk

was written by the author Melvin Burgess. The main characters, Tar and Gemma, get together and then leave home. They end up living with some squatters. In the second half of the book they become heroin

addicts. It’s quite detailed in its explanation of what drugs can do. When I say I was knowledgeable on drugs, of course I was aware of the names of different drugs, but I didn’t know the details of how they were taken.

Junk

was there with all the details and it also made me realise that drugs affected lots of other people apart from just my family. When the book came out in 1996 it was quite controversial because even though it was aimed at young adults, many parents thought it was unsuitable for their teenagers.

Everyone was talking about it at school and I wanted to find out what it was all about for myself. One night after school, I went to WHSmith in Beaconsfield, which is a town near Welders. I saw it on the shelf. Firstly, I was attracted to the bright-green cover with a needle on the front. But of course I’d heard what it was about, so I wanted to read it and know what was going on. As I flicked through the pages, I really related to the story and could understand what the characters were going through. I’m pleased I read

Junk

. It gave me a greater understanding of drugs and it actually explained a lot of things to me. I would recommend this book to anyone. When I’m reading in my head, I don’t struggle to read as much as if I have to read out loud. Also, I found it easier to educate myself – I learned loads more that way than sitting in a classroom being force-fed facts!

I think it’s so stupid of parents not to talk to their kids and inform them about drugs. I was given every reason not to become a drug addict. But this is the interesting bit: if it hadn’t been for my family being so open about drugs then I think I would have been dead by the time I was twenty because they wouldn’t have known how to help me.

My mum has always known what to do and where to go when she’s suspected I’ve needed help. What if she hadn’t?

O

BVIOUSLY,

when we got to school age, it meant we couldn’t go on tour with dad any more. That was saved for the school holidays and, if he was only in Europe, weekends.

I used to absolutely hate it when my parents went on tour. We all did. I used to try every trick in the book to get them to stay. In my bedroom in Welders, surrounded by my fairyland mural, I’d stand on my bed and piss all over the duvet and sheets. That would mean I had to go and sleep in Mum and Dad’s bed. I did that from the age of five until I was thirteen. When I was in bed with my mum and dad, I knew they weren’t going away on tour – or rather, I thought they couldn’t go away on tour. I just hated it so much when I was apart from them. Of course, we had some really great nannies at times like Kim, who came from Newcastle. She was lovely. And when she got married I was a bridesmaid with Aimee and Jack was the pageboy. But as lovely as some of the nannies were, I would have preferred it if Mum and Dad had stayed at home.

Every time they went away, I would write letters begging them: ‘Please don’t leave me.’

My mum’s kept all of them. They’re at Welders in one of the trunks on the landing outside our bedrooms. My mum keeps everything, although she doesn’t keep anything that isn’t attached to a memory. But

most things are. I think it’s something you can only fully understand if you’re a mother yourself. At Welders, she has one room that’s just dedicated to photographs. She has cupboards and cupboards full of them. She also has an island in the middle of the room with a glass top. Underneath she has laid out all her favourite photographs so when she goes in she can see them all.

I don’t keep everything, but I have trouble throwing things away because I’m worried I’m going to want it later in life. When you’re dead you can’t take anything with you, but while I’m still living I like to know where I’ve been and keep the things that have meant something to me.

It’s absolutely heartbreaking to read over the letters that I sent Mum before she went away. There’s one that says – and I must have been naughty because I’m apologising for something too – ‘To Mummy. I am sorry. Please forgive me. I love you very much. You do not know how much I love you. Please don’t go to Japan. I will miss you too much. Love from Kelly.’

I’d scribble them while sitting on my bed in my bedroom. Then I would run out and down the spiral staircase that led to my parents’ bedroom. I would tip-toe to their door, fold up the piece of paper and push it through the gap at the bottom so they would find it when they came to open the door.

In the days leading up to my parents’ trips abroad, I would spend hours sitting on that spiral staircase sobbing, ‘Don’t go. Please don’t go, Mummy and Dadda.’ (I always refer to my father as Dadda. I still do today.)

‘In the days leading up to my parents’ trips abroad, I would spend hours sitting on that spiral staircase sobbing, “Don’t go. Please don’t go, Mummy and Dadda.”’

W

HEN

my father used to go away on his own, we had a rotation list for my mum’s bed. This is how it went: my mum would sleep on the right-hand side, one of us would be in the middle, one on the left and another would lie at the bottom. Actually, it was only me and Jack who swapped, Aimee would always be next to Mum.

On some trips, Mum and Dad would have to leave really early in the morning. They didn’t like to wake us because it was too early. Also, it would have made us even more upset. So Mum devised this little way of letting us know how much we were loved and that she was thinking about us too. It must have been really hard for her to leave behind her babies. Mum would go around the house and write on everything in one of her red lipsticks. I would lift up the toilet seat in the bathroom and there would be a message written underneath the lid saying: ‘I love you, Kelly.’ Or she would write on the wall behind my bed: ‘Love you. Love, Mummy.’

They would be all over the place: on the walls, on the fridge door, in the bathroom. She still does it today. It’s her thing. Jack still has one of those messages. She wrote it when we were living in Welders. It’s in red lipstick on the wall above his bed.

As soon as I woke up on the morning Mum and Dad had left the house, I would race down to their bedroom. I’d hunt around for one of Mum’s nighties and I would scrunch it to my face and breathe in

her perfume. I loved the fact it reminded me of my mum and it was a tremendous comfort. I would sleep with it under my pillow until the day they returned and then I would put it back in her drawer until next time.

During the time they were away, my life would be ruled by the stupid tour books that every band’s management company has made up. They basically have the dates for each venue followed by the names and numbers of all the hotels Mum and Dad would be staying at in each city. Then there would be a page of names and numbers of every single person involved in the tour. I would go to my mum’s office and find the tour book and keep it opened on the calendar page. After my dad had performed at each venue, I’d do a bright red tick across it and count down the days.

When Mum went on tour with my dad she was incredibly torn at times. There had been a period when I was about six that we moved to America for a few months and had actually gone to school there. It had been so my mum could keep us all together. We soon moved back to the UK. But moving out there permanently was obviously something that my mum was thinking about.

In 1996, my mum came up with an idea for a festival called Ozzfest. It was a massive tour around America of heavy metal and hard rock bands. Some of them were already established and others were up and coming. It was really successful and Dad was the headline act with his band. Because it was an American festival, it meant my mum had to go there more often for meetings and to set things up.

In the summer after I’d turned thirteen there was a school trip to Wales. Aimee had also joined the school at this point. In the past, we had not always been able to go on the school trips because we would sometimes be away with Dad. But we wanted to be with our friends, so we signed up for the three-day visit.

When we got to the hostel, we soon realised that the food was going to be shit. Aimee and I are really fussy eaters. We don’t like fancy food. On the menu it was all kidney and haggis and pretty crazy shit. Well, it was to us. It wasn’t that I was so much bothered about the taste. I just didn’t like the idea of eating some poor fucking animal’s kidneys.

Aimee and I hardly ate a thing for three fucking days and we were absolutely starving. The packed lunch that my mum had done for us both to eat on the way, we’d made last during the trip. We’d rationed it to keep us going. On the coach on the way back our stomachs were rumbling. When we stopped at a service station on the motorway, I turned to Aimee who was sitting in the seat behind me and said, ‘Aimee, let’s get as much food as we can.’ The problem was, I only had a few pennies left because we’d only been allowed to take five pounds and I’d spent it on souvenirs and shit.