Fifties (151 page)

Authors: David Halberstam

Willoughby, Charles,

105

Wilson, Bill,

730

,

731

Wilson, Charles E. “Engine,”

118

,

119

,

120

,

128

,

129

,

361

,

375

,

395

,

490

,

618

,

621

,

622

,

623

,

625

Wilson, Doll,

175

Wilson, Dorothy,

174

,

177

Wilson, Kemmons,

173-79

,

471-72

Wilson, Sloan,

521-25

,

528

Windham, Donald,

260-61

Winstead, Charlie,

338

Winter, Bill,

438

Witness

(Chambers),

10

,

13

,

16

Wolff, Kurt,

528

Woman Rebel, The

,

284

women’s movement:

employment and,

586-89

Friedan and,

591-97

magazines and,

589-93

,

595-97

Metalious and,

579-80

suburbs and,

143

,

589-90

see also

Sanger, Margaret

Women’s Political Council,

545

Wood, Audrey,

260

,

261

Wood, Natalie,

564

Worchester Foundation for Experimental Biology,

290-92

,

600

,

602

,

605

World War I,

22

,

38

,

82

,

442

World War II,

26-27

,

29

,

66

,

73

,

82

,

117

,

118

,

208

,

215

,

250

,

362

,

366

,

373

,

381

,

436

,

530

,

531

,

587

,

688

black migration and,

442-45

colonialism and,

358-59

Democrats affected by,

3-5

,

9

housing and,

134

LeMay and,

354-55

Republicans affected by,

3-5

Ridgway in,

110-11

V-2 rocket and,

607-11

Wouk, Herman,

181

,

184

Wright, Moses,

430

,

431

,

434

,

435

,

441

Wyden, Peter,

726

Wyrick, William,

72

Yalta conference,

16-17

,

58

,

63

Yazoo City

(Miss.)

Herald

,

429

Ydigoras Fuentes, Miguel,

376-77

Yergin, Daniel,

117

Yewl, Ken,

488

Yost, Norman,

50

Zemurray, Sam,

377

AUTHOR’S NOTE

I

AM A CHILD

of the fifties. I graduated from high school in 1951, from college in 1955, and my values were shaped in that era. I wanted to write a book which would not only explore what happened in the fifties, a more interesting and complicated decade than most people imagine, but in addition, to show why the sixties took place—because so many of the forces which exploded in the sixties had begun to come together in the fifties, as the pace of life in America quickened. In large part this book reflects my desire as a grown man to go back and look at things that happened when I was much younger. I was a reporter in the South in the early days of the civil rights struggle; I went to Mississippi in 1955 immediately after graduation specifically because the Supreme Court had ruled on the Brown case the year before, and I thought therefore the Deep South was the best place to apprentice as a journalist. I was a reporter in West Point, Mississippi, when the Emmett Till trial took place in Sumner that summer. As I became aware of the vast press corps which was arriving in Tallahatchie County to cover the case, I knew instinctively that something important was taking place. I got an assignment from the old

Reporter

magazine to do a piece on the trial, and I faithfully read the various papers of the different reporters covering it. On my days off, I went over to watch them at work there. (I also managed to stay as far from Clarence Strider as I could—I still remember his threatening figure.) But when I sat down to write at the time, I was not able to pull off the piece I wanted, and it fizzled. Some thirty-eight years later I have taken what I sensed but could not articulate then, and tried to make it a part of this book. That is true of other experiences from those days as well. I have a clear memory, from countless visits to the bus stations in Nashville, Memphis, and Jackson, Mississippi, of large families of blacks headed North with all of their belongings. Clearly a great migration was then taking place, and I saw it, yet did not see it. This event of great historic importance went right by me until I finally understood its meaning some twelve years later when Andy Young talked to me about it one day while I was reporting on Martin King. Later, when I was a reporter in Nashville, I was assigned to cover the country music beat. That led to a friendship with Chet Atkins, the distinguished guitarist, who was also in charge of RCA’s studios, and who would, on occasion, discreetly let me sit in when the young Elvis was recording there. Yet only later would I become fully aware of the importance of the new music as a sign of the political, economic, and social empowerment of the younger generation.

A book as long as demanding as this requires the help of many colleagues and I would like to thank among others my editor Douglas Stumpf, his assistants Leslie Chang, Erik Palma, and Jared Stamm. I am also grateful to Carsten Fries, Veronica Windholz, and Patty O’Connell at Random House, Fernando Villagra, Amanda Earle, Danny Franklin, Martin Garbus, Bob Solomon, Gary Schwartz, Ken Starr and Philip Roome, the staff of the New York Society Library where I spent long and happy hours, Pat Martin at the Worcester Foundation, Geoffrey Smith at the archives at Ohio State, who helped me look at Bill Huie’s papers, Vicky Lem McDonald at the Museum of Broadcasting, and Keith Roachford in Senator Bill Bradley’s office for helping me with the transcript of the Quiz Show hearings.

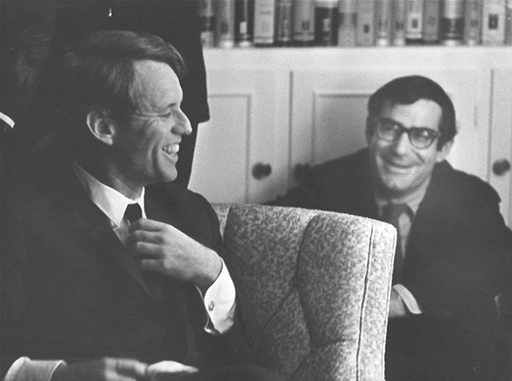

A Biography of David Halberstam

David Halberstam (1934–2007) was a Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist and bestselling author. He is best known for both his courageous coverage of the Vietnam War for the New York Times, as well as for his twenty-one nonfiction books—which cover a wide array of topics, from the plight of Detroit and the auto industry to the captivating origins of baseball’s fiercest rivalry. Halberstam wrote for numerous publications throughout his career and, according to journalist George Packer, single-handedly set the standard of “the reporter as fearless truth teller.”

Born in New York City, Halberstam was the second son of Dr. Charles Halberstam, an army surgeon, and Blanche Levy Halberstam, a schoolteacher. Along with his older brother, Michael, Halberstam was raised in Westchester County and went to school in Yonkers. He attended Harvard University, where he was the managing editor of the

Crimson

, the student-run newspaper. Dedicated to forging a career in journalism, Halberstam worked with the

West Point Daily Times Leader

in Mississippi after graduation and at the Nashville

Tennessean

, where he covered the civil rights movement, a year later. Halberstam joined the Washington bureau of the

New York Times

in 1960. He worked as a Times foreign correspondent, moving to Congo and then to South Vietnam to cover the war in 1962.

Throughout Halberstam’s coverage of the Vietnam War, he was committed to reporting what he saw despite intense and continuous political pressure. Halberstam reported on the corrupt nature of the American-backed government in Saigon. Unlike many of his colleagues, he refused to report the misinformation that American commanders fed to the press, choosing instead to talk to soldiers and sergeants on the frontlines. His steadfast dedication left President Kennedy so infuriated that he personally asked Arthur Ochs Sulzberger, then-publisher of the

New York Times

, to replace Halberstam. Sulzberger refused.

Halberstam won the Pulitzer Prize for his coverage of Vietnam and worked for the Times’ Warsaw bureau after the war. After leaving the

Times

in the late sixties, Halberstam turned his focus to writing books and magazine articles. He described his books as stories of power—sometimes used wisely, sometimes disastrously. Halberstam quickly established himself with

The Best and the Brightest

(1972), a blistering, landmark account of America’s role in Vietnam. For each social or political book he published—such as

The Powers That Be

,

The Fifties

, and

The Children

—Halberstam wrote one on sports, one of his favorite subjects. His books were regularly praised for their impeccable detail as well as for their absorbing narrative style.

Halberstam died in a car accident in Menlo Park, California, in 2007, at the age of seventy-three. He was en route to an interview for an upcoming book about the 1958 National Football League championship game between the New York Giants and the Baltimore Colts. His obituary in the

Guardian

hailed him as “one of the most talented, influential and prolific of the American journalists who came of age professionally in the 1960s.”

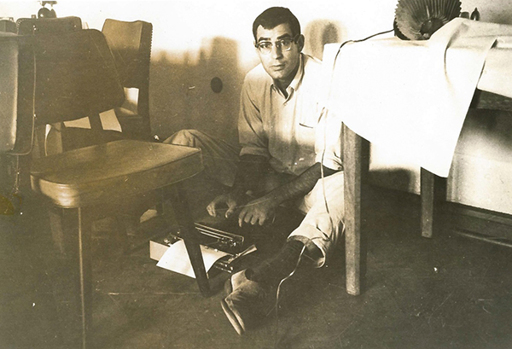

Young Halberstam and his typewriter in the Congo in 1960.

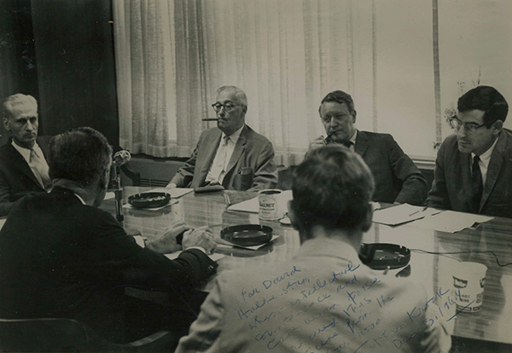

An editorial meeting at the

New York Times

office, around 1962. Halberstam is at far right; Scotty Reston, who hired Halberstam, is to his right.

Halberstam, shown second from left, walking with military officers in Vietnam, around 1962.