Flight of the Eagle: The Grand Strategies That Brought America From Colonial Dependence to World Leadership (38 page)

Authors: Conrad Black

Clay spoke on February 5 and 6 and emphasized that secession was not a justified or effective remedy for southern concerns, and that the preservation of the Union was in the interests of and the duty of all, and to that end, mutual concessions were needed and appropriate. Calhoun, gravely ill and on the verge of death, sat while his address opposing Clay was read for him by Senator Mason of Virginia, and he said, one last time, that the South had to have entrenched equality in the newly taken territories, in a constitutional amendment restoring the South’s equality and ability to protect herself, “before the equilibrium between the sections was destroyed by the actions of this [the federal] government.”

Calhoun died a few weeks later, on March 31. By the last comment, as he explained posthumously in his

Disquisition on Government,

he meant that the Constitution had always intended a de facto dual ratification for any important initiative, and that this was being steadily eroded by what he declined to recognize as the forces of history. Webster followed on March 7 with another of his mighty addresses, supporting Clay’s resolutions, beginning that he was not speaking for his state or region but “as an American ... I speak today for the preservation of the Union. ‘Hear me for my cause.’” He said that matters of soil and climate excluded any recourse to the economics of slavery in the territories under discussion, and that the subject should not arise at all. Calhoun’s constitutional divinations were completely unrigorous; Washington, southern slaveholder though he was, spoke at all times of an indissoluble Union; Jefferson and Madison, though states’ rights advocates and rather quavering in their approach to slavery, recognized slavery’s moral frailty, and none of them ever hinted at an imposed equality between sections. Webster was close to the mark in implying that as states were admitted, as they would be, across the continent to the Pacific, there would be no economic rationale for slavery in them at all, quite apart from the moral concerns slavery raised, and that Calhoun’s notion of stopping history, even as the body of the nation was divided into a northern torso and southern tail, was nonsense at every level, the death-bed revisionism of a formidable but irrational apologist for a morally bankrupt, doomed regime.

Disquisition on Government,

he meant that the Constitution had always intended a de facto dual ratification for any important initiative, and that this was being steadily eroded by what he declined to recognize as the forces of history. Webster followed on March 7 with another of his mighty addresses, supporting Clay’s resolutions, beginning that he was not speaking for his state or region but “as an American ... I speak today for the preservation of the Union. ‘Hear me for my cause.’” He said that matters of soil and climate excluded any recourse to the economics of slavery in the territories under discussion, and that the subject should not arise at all. Calhoun’s constitutional divinations were completely unrigorous; Washington, southern slaveholder though he was, spoke at all times of an indissoluble Union; Jefferson and Madison, though states’ rights advocates and rather quavering in their approach to slavery, recognized slavery’s moral frailty, and none of them ever hinted at an imposed equality between sections. Webster was close to the mark in implying that as states were admitted, as they would be, across the continent to the Pacific, there would be no economic rationale for slavery in them at all, quite apart from the moral concerns slavery raised, and that Calhoun’s notion of stopping history, even as the body of the nation was divided into a northern torso and southern tail, was nonsense at every level, the death-bed revisionism of a formidable but irrational apologist for a morally bankrupt, doomed regime.

William H. Seward, a rising star of the anti-slavery Whigs, who would be a presidential contender and distinguished secretary of state, spoke on March 11 and opposed Clay’s resolutions because he wanted slavery contained as if by the Wilmot Proviso: no new slave states carved from the territories. He was one of the leaders of the emerging consensus in the North, that slavery could be tolerated where it was but there was no excuse for tolerating its expansion, and Seward declared legislative compromises in general to be “radically wrong and essentially vicious.” He didn’t dispute that the Constitution implicitly accepted the legitimacy of slavery, but spoke of a “higher law” that justified avoiding protection of it. He was morally very arguably correct, but this was a considerable liberty in the realm of constitutional law, as long-standing legal conditions cannot simply be dispensed with because a later generation finds moral problems with them. Jefferson Davis opposed Clay’s resolutions for the same general reasons as Calhoun, as did, to a large extent, Thomas Hart Benton. Chase opposed for reasons similar to Seward’s. Douglas, and the late presidential candidate General Lewis Cass of Michigan, supported the resolutions.

The resolutions were sent to a select committee of 13 senators, chaired by Clay, which came back with an omnibus bill and a special bill abolishing the slave trade in the District of Columbia, on May 8. President Taylor, who opposed reorganizing the new territories, apart from California, into Utah in the north and New Mexico in the south, as was now the proposal, died on July 9 after over-strenuous July 4th celebrations. Vice President Fillmore succeeded him and was a less-ardent New York critic of slavery than his colleague Seward, and supported Clay’s resolutions. Though Taylor was a more substantial figure than Fillmore, Fillmore was better suited to achieve a compromise, and once again, Providence had assisted the United States. Taylor might not have been an insuperable obstacle as Tyler and Polk would have been, but he would not have been much help to Clay either. Clay and Douglas, now the Democratic leader in the Senate, though only 37, worked through the summer (though Clay had to retire from overstrained health, and did not play a leading role in the Senate again) to get those who put the Union ahead of opposition to, or militant and integral defense of, slavery together behind a reformulated compromise, which was enacted in five laws between September 9 and September 20. Most of the Unionists who favored a Wilmot restriction on the spread of slavery came over to Clay and Douglas, joining the softer disapprovers of slavery and the doughface northern appeasers of the South, and some southerners who were content with half a loaf. Only the outright abolitionists, the dogmatic Wilmotites like Seward, and the quasi-secessionist Calhounites were outside the compromise coalition when the new set of bills was voted.

The new legislation admitted California as a free state by a heavy majority; divided the acquired territory between Texas and California into two territories, Utah and New Mexico, where, in the kernel of the compromise, applications for statehood from component parts could be accepted whether slavery was included or not, “as their constitution may prescribe at the time of their admission”; tightened the discouragement of fugitive slaves; and abolished the slave trade in the District of Columbia. The Fugitive Slave Act passed the Senate 27 to 10 and the House 109 to 76, illustrating that the North was more concerned with the conceptual irritation of slavery as an institution than with helping individual slaves rebelling against their state of hopeless servitude.

This act set up special U.S. commissioners who could issue warrants for the arrest of alleged fugitive slaves after a summary hearing solely on the affidavit of a claimant. Commissioners received $10 for every such application granted and $5 for every one refused, a clear and egregious incitement to the avoidance of a fair finding. The commissioners could form posses, and those accused of being fugitive slaves but denying it had no right to a jury trial or to give evidence themselves. Those abetting the flight of slaves, deliberately or negligently, were subject to fines of $1,000, indemnity of the economic value of the fugitive slave(s), and imprisonment for up to six months. It was a disgraceful law that effectively entrenched the principle that African Americans were subhumans without civil rights, unless they were emancipated, at which point they miraculously metamorphosed into citizens.

It was inherently absurd that an act of emancipation by the ostensible owner would transform an animal without rights and subject to starvation, sexual violation, whipping, or even murder, without recourse, into a citizen with civil rights identical, theoretically, to those of the president of the United States. And the Fugitive Slave Act was a dramatic setback to human rights in America, considering that when Benjamin Franklin had been the president of Pennsylvania 65 years before, any slave who spent six consecutive months in that state was automatically free, and now all states were pledged to yield to these draconian enforcement procedures of the federal government. Northern abolitionists said from the start that they would not comply with the Fugitive Slave Act, and some states, such as Vermont, countered the Fugitive Slave Act with expanded guarantees of civil liberties. People trying to recover slaves were sometimes abused and hampered and the federal commissioners responsible for enforcement had a very difficult time in some northern states, and had problems getting local courts to enforce the act. There were riots, some entailing loss of life, in a number of northern cities, particularly New York, Boston, and Baltimore.

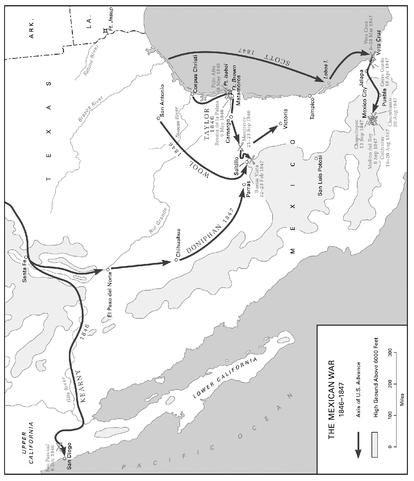

Mexican War. Courtesy of the U.S. Army Center of Military History

It was a high price for the Union but seemed to stabilize public policy and settle the political atmosphere. Secessionist candidates were defeated by Unionists throughout the South in elections in 1851, while the strenuous abolitionist Charles Sumner was elected U.S. senator from Massachusetts the following year. The Compromise of 1850, as it was called, contained a time bomb that could have been foreseen as mortally dangerous: the provision that each territory applying for statehood would determine itself whether it would be a free or slave state was an invitation to civil war in each state as the date of its application approached. Clay and Webster had done their best and they were great legislators and great patriots, but they were trying to palliate an intractable issue. Either slavery was morally acceptable or it was not. Endless expressions of distaste or disapproval among the free-state majority only provoked southern ambitions to secede; by not abdicating the right to denounce or restrict slavery, the North pushed the South toward the only apparent means available to it to secure slavery: the dissolution of the Union. And there was no method of ending northern discomfort with slavery except turning a permanent blind eye to it, which was impossible as long as it was expanding, or going to war to suppress it, or acquiescing in the break-up of the country.

Webster was right that it was nonsense to contemplate slavery in places where African American laborers were not more productive than Caucasian workers. There was no economic rationale for slavery in cooler climates than the cotton-producing South. Calhoun’s demand for the imposition of a false equality of regions was preposterous, as people vote with their feet in such matters, and slave-holding was an odious system. And the demand for the establishment of slavery in places like New Mexico, where there was no possible economic use for it, was insolent. By not eliminating the recurrences of frictions, the Compromise of 1850 assured their escalation. This was clear enough with the publication in 1852 of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s

Uncle Tom’s Cabin,

a dramatization of the problems of the life of the slave that sold a completely unprecedented 1.2 million copies in a little over a year. The Compromise of 1850 bought time.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin,

a dramatization of the problems of the life of the slave that sold a completely unprecedented 1.2 million copies in a little over a year. The Compromise of 1850 bought time.

It would have been better to produce a continuation of the 1821 Missouri Compromise line to the California border, and to produce a magnanimous scheme whereby the federal government would incentivize emancipations generously, or even to impose a code of treatment that at least gave the slaves the rights accorded later by legislation against cruelty to animals. None of this would have been easy to pass, but it wasn’t tried, and the Compromise was going to lead quickly to renewed and intense friction, though it earned Clay the title, with the usual American hyperbole, “the Great Pacificator” (as Calhoun, before he became a robotic and belligerent slavery apologist, was called “the Young Demosthenes,” and as Webster was long known as “the Godlike Daniel”). As with all resolutions of tense impasses that are not comprehensive, such as the Versailles and Munich Conferences (Chapters 9 and 10), when the problems it had been hoped were settled rose up again, it was with increased venom and escalated hostility between the factions that had thought the problems composed.

As a solution and durable extension of the Jackson system, the compromise was a stopgap, but as strategy—and this may not have been in Clay’s mind but it might have been in the thoughts of some others, possibly including Douglas—it was decisive to the survival of the country. In the ensuing decade, the U.S. population would increase by another 35 percent, from 23 to 31 million, 22.4 million in what would be the North (all but 448,000 free, and the slaves were in Kentucky, Missouri, and Maryland, and would be relatively easy to emancipate) to 8.7 million in the South, and of those, only 5.1 million whites. Even if Kentucky, Maryland, and Missouri, all contested states but with northern majorities, are divided between North and South, it only narrows the 22-to-5.1-million advantage of northern over southern Whites to about 21 to 6 million. In that decade, almost three million people arrived in the United States as immigrants, more than four-fifths to the North (plus all of the 800,000 immigrants who arrived in the first half of the 1860s). The northern states would mobilize more than three times as many men to their armed forces from 1861 to 1865 as the South and had a vastly larger industrial base to support an armed enforcement of the Union. Andrew Jackson and Henry Clay kept together for a further 30 years the Union that Washington, Franklin, Jefferson, Madison, Hamilton, and Adams had founded and led for nearly 40 years, so that the greatest of all American leaders could make the Union “one and indivisible,” and permanent, at last.

While the country was absorbed by the struggle for the Compromise, there were some foreign policy developments. Taylor’s secretary of state, John M. Clayton, negotiated a treaty with the British minister in Washington, Sir Henry Lytton Bulwer (the Clayton-Bulwer Treaty), after both countries had been active in Nicaragua, preparing to build an isthmian canal between the Atlantic and the Pacific. The two agreed not to seek or assert exclusive control over, nor fortify, such a canal; guaranteed jointly the neutrality and security of any such canal; agreed to keep the canal open to the ships of both countries equally; and promised not to infringe on the sovereignty of any of the Central American states.

Other books

Rumbo al cosmos by Javier Casado

The Widow's Guide to Sex and Dating by Carole Radziwill

Redzone by William C. Dietz

College Boy : A Novel (9781416586500) by Tyree, Omar (COR)

Pleasured by the Viking by Michelle Willingham

Five Wicked Kisses - A Tasty Regency Tidbit by Anthea Lawson

Michael's father by Schulze, Dallas

Cómo descubrimos los numeros by Isaac Asimov

No Easy Hope - 01 by James Cook

A Carra King by John Brady