Flight of the Eagle: The Grand Strategies That Brought America From Colonial Dependence to World Leadership (46 page)

Authors: Conrad Black

6. THE END OF THE WAR AND THE DEATH OF LINCOLN

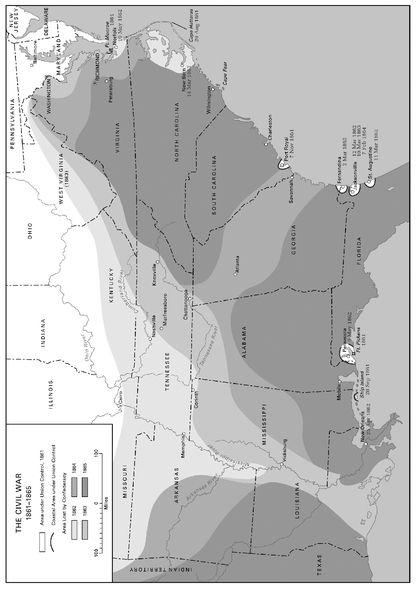

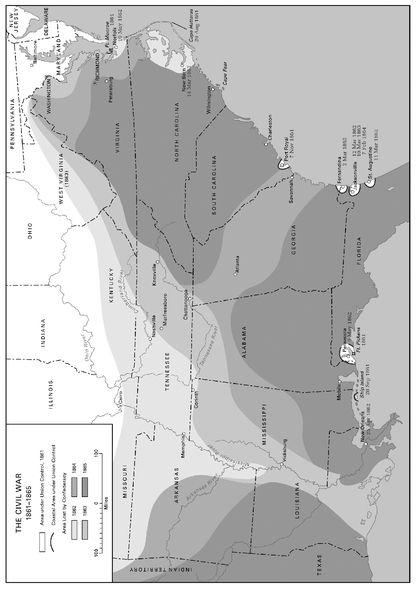

The election sounded the death-knell for the South. Sherman ordered that Atlanta be burned to the ground on November 7 (the day after the election), the city having been evacuated, but was persuaded by the city’s leading Roman Catholic clergyman (Sherman was a semi-Roman Catholic and he had a son who became a Jesuit priest) to spare the city’s churches and hospitals. It was still a dramatic, and for the South, traumatizing conflagration. It conformed to the grim and stern Lincoln-Grant-Sherman view that nothing less than a comprehensive and total defeat would eliminate in spirit as well as fact the vocation to independence of the South. Sherman departed the smoking ruins of Atlanta (about 70 percent of it was razed) on November 14 with 60,000 men stretched out on a front 60 miles wide, to march the 300 miles to the sea at Savannah. Sherman’s orders were to “forage liberally on the land and destroy anything of military use to the enemy.” Practically everything was destroyed—crops, buildings, roads, railways, bridges. Sherman occupied Savannah on December 22, having scorched to ashes and utterly destroyed most of Georgia. Savannah was not disturbed, and Sherman strictly reimposed discipline, having turned a blind eye to the most rapacious looting on the five-week march. The reality of what the war had become shocked even some northerners, startled the world, and profoundly shook what was left of southern morale.

Hood gave up fighting Sherman and moved to Sherman’s west all the way back into Tennessee, thinking he might strangle Sherman’s communications (not that it would have much mattered, as his armies took what they wanted on their route of march). It was a mad and desperate plan. Hood encountered Union general John Schofield in an engagement won by the Union, and then his errant, purposeless army came face-to-face with Thomas’s seasoned Army of the Cumberland at Nashville, where Sherman had sent Thomas to rid him of Hood. Hood’s army was completely destroyed and fragmented into disparate groups of stragglers and deserters and guerrillas. More than 20,000 Confederates were removed from the war in one way or another. Mississippi, Alabama, Florida, and Georgia were now separated from the Confederacy and Tennessee entirely occupied by the Union. The Confederacy was now reduced to Virginia and the Carolinas. Grant was south of Richmond and grinding Lee’s army in the siege of Petersburg, and in the final phase of the Anaconda Plan, the dreaded Sherman turned north and drove into the Carolinas, wreaking even greater havoc than he had in Georgia. Lee reversed Davis’s error and brought back the South’s most talented general, next to Lee himself, Joseph Johnston, with the unenviable task of halting Sherman’s juggernaut with much inferior forces. The Union navy employed amphibious forces to seize Fort Fisher and shut the port of Wilmington, North Carolina, in January and February 1865, and what was left of the Confederacy was racked by riots and demonstrations against shortages, speculation, skyrocketing prices, evaporation of income, and heavy casualties.

Sherman had eliminated South Carolina as a functioning state by the end of February and fought and won his last battle with Johnston at Bentonville, North Carolina, on March 19 and 20. But Johnston fought admirably and retired in good order despite Sherman’s lack of reluctance, unlike Union generals earlier in the war, to give chase and set reserves on the retreating enemy. Grant’s nine-month siege at Petersburg, as he had planned, had finally almost strangled Lee’s army. Grant was deploying 115,000 battle-hardened veterans to Lee’s 54,000, many of them new recruits. On April 1, Lee attacked at Five Forks, near Petersburg, but was repelled by Sheridan, and Lee had Davis called out of a church service and advised that he had ordered the immediate abandonment of Richmond and Petersburg. (At the Hampton Roads Conference on February 3, Lincoln himself met with Confederate vice president Stephens, an initial opponent of secession in 1861. Davis had instructed Stephens to insist on recognition of southern independence as a condition for peace, a mad delusion at this point, and the conference ended after a couple of hours.)

Davis fled his capital as Lee went to Lynchburg and prepared to try to embark his army, now reduced to 30,000 men, by rail to North Carolina to meet with Johnston for a final stand against the overwhelming encircling forces of Grant and Sherman. Grant moved like a cat on his trail and Sheridan blocked Lee’s routes to the west and south. The Army of Northern Virginia was almost out of food and ammunition. Sheridan telegraphed Lincoln: “If the thing is pressed I think Lee will surrender.” Lincoln instantly replied to Grant, quoting Sheridan’s telegram and adding: “Let the thing be pressed”

Grant, his armies now sensing victory so keenly that, as he wrote, the infantry foreswore rest and rations and “marched about as rapidly as the cavalty,”

88

invited Lee to surrender. Lee asked for terms, and the two met at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865. As befits great generals and exemplary gentlemen, it was without histrionics or even negotiation, and was entirely courteous. They reminisced discursively about “the old army,” and on request by Lee, Grant gave his terms and then wrote them, and Lee accepted straightforwardly. His army was now crumbling from famine and desertions, including the colonel, sole survivor of his regiment, and owner of the house where Grant was billeted, who dropped out near his home and surrendered personally to the Union commander. Grant permitted Confederate officers to retain their horses and sidearms and did not ask for prisoners. All weapons of war and ammunition were surrendered, the Army of Northern Virginia ceased operation, and all officers gave their word that no one would resume hostilities. The commander of the Union Armies ordered that 25,000 full rations be issued at once to their late and distinguished enemy. The Army of Northern Virginia self-demobilized and its survivors returned home, after visiting the Union quartermaster and commissary exactly as Union troops would. Grant ordered an end to what began as a 100-gun salute of victory, and ordered there be not the slightest gesture of exultation nor any act disrespectful of, as he put it, “a foe who had fought so long and valiantly, and had suffered so much for a cause, though that cause was, I believe, one of the worst for which a people ever fought, and one for which there was the least excuse.”

89

88

invited Lee to surrender. Lee asked for terms, and the two met at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865. As befits great generals and exemplary gentlemen, it was without histrionics or even negotiation, and was entirely courteous. They reminisced discursively about “the old army,” and on request by Lee, Grant gave his terms and then wrote them, and Lee accepted straightforwardly. His army was now crumbling from famine and desertions, including the colonel, sole survivor of his regiment, and owner of the house where Grant was billeted, who dropped out near his home and surrendered personally to the Union commander. Grant permitted Confederate officers to retain their horses and sidearms and did not ask for prisoners. All weapons of war and ammunition were surrendered, the Army of Northern Virginia ceased operation, and all officers gave their word that no one would resume hostilities. The commander of the Union Armies ordered that 25,000 full rations be issued at once to their late and distinguished enemy. The Army of Northern Virginia self-demobilized and its survivors returned home, after visiting the Union quartermaster and commissary exactly as Union troops would. Grant ordered an end to what began as a 100-gun salute of victory, and ordered there be not the slightest gesture of exultation nor any act disrespectful of, as he put it, “a foe who had fought so long and valiantly, and had suffered so much for a cause, though that cause was, I believe, one of the worst for which a people ever fought, and one for which there was the least excuse.”

89

Johnston continued as best he could, but Sherman occupied Raleigh, North Carolina, on April 13. The Confederacy was almost entirely occupied and Johnston was effectively surrounded, and without ammunition or stores. He surrendered his army of 37,000 on April 17, despite the itinerant and deranged Davis’s poor wail of appeal to continue. Sherman, as magnanimous in victory as he was remorseless in battle, gave his gallant and resourceful adversary even more generous terms than Grant had accorded Lee. (Sherman and Johnston became friends, and Johnston died 26 years later from pneumonia contracted from attending Sherman’s funeral and burial, under-clothed for the raw northern weather. He was 84, 13 years older than Sherman, and he said Sherman would have done the same had the roles been reversed.)

The supreme figure of the great and terrible drama and providential redeemer of America, including the South, did not survive the war to win the peace. In what many consider the greatest of all his oratorical triumphs, Abraham Lincoln said in his second inaugural address on March 4, 1865, that “The progress of our arms, upon which all else chiefly depends, is as well-known to the public as to myself and it is, I trust, reasonably satisfactory and encouraging to all. With high hope for the future, no prediction in regard to it is ventured.... Fondly do we hope, fervently do we pray, that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away” (a line of poetry). “Yet if God wills that all the wealth piled up by the bondsman’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and that every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said ‘The judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.’ With malice toward none, with charity for all ... let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and a lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.”

This in the plainest and most powerful terms was Lincoln’s strategy for America: the complete, unarguable, bone-crushing defeat of secessionism, and abolition of slavery, which he called “a peculiar and powerful interest,” and the eventual determination that it is an evil that must be ended, for which purpose “He gives to both North and South this terrible war as the woe due to those by whom the offense came.” Lincoln made no effort to restrain Sherman’s depredations, but wished a generous peace of forgiveness and reconciliation. Lincoln was initially prepared to pay something to slaveholders for emancipation, to pick up some of the Confederate debt, and to readmit the southern states to the Union easily, as long as they pledged loyalty to the Union. He never regarded the insurgents as traitors. He knew that such a reconstituted Union would emerge immensely powerful, economically, militarily, and morally, that no power would ever dare to meddle in the Americas again, and that it would not be long before the Europeans, so complicatedly and finely balanced between themselves, would be soliciting America’s assistance to one side or another there, rather than presuming to offer mediation and imagining the Americas were any rightful province of their interest.

The world was, indeed, appropriately awed by the ferocity of what was, if the various Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars are divided up into a series of wars of shifting coalitions, the greatest war in the history of the world. The U.S. Civil War produced 360,000 Union and 300,000 Confederate combat deaths, about 90,000 civilian deaths, and approximately 475,000 wounded, military and civilian. The Union had almost four times the free population and twice as many combatants as the Confederacy, and roughly three-fifths of the 1.25 million total casualties, about 4 percent of the total free population, North and South, black and white, men, women, and children. No foreigners had foreseen the vehemence and fury of the struggle, or had imagined the emergent might of the victorious armies. Those who had thought America the light of the world, now knew it to be so. Those who had lamented the moral palsy of slavery behind the Jeffersonian message, rejoiced. And those who had doubted the strength, as opposed to the diplomatic agility, polemical talent, and geographic good fortune of the Americans and their leaders, saw the strength of the American people, of their devotion to their country and its ideals, and were struck almost dumb by the genius and humanity of their leader.

Lincoln visited Richmond on April 4, arriving by ship, first a flotilla, then the captain’s launch, and finally, so heavy was the wreckage and mass of dead horses and undetonated torpedoes in the water, by rowboat. The conquering president was completely unruffled and found it reminiscent of the man who had come to ask him for a post of consul in a great foreign city and gradually scaled back his requests to humbler and humbler positions, and finally to the gift of a well-worn pair of trousers.

90

As he stepped ashore, many African Americans greeted him on their knees and Lincoln helped raise them up, and said “You must kneel to God only and thank him for the liberty you will hereafter enjoy.” Demonstrating that he had never ceased to be the president of the United States, he walked two miles to Jefferson Davis’s office, with security provided by a black regiment, and followed by a large and mainly black crowd of well-wishers, and was regarded from windows with neutral curiosity. He sat in Davis’s desk chair without a hint of triumphalism, asked for a glass of water, and authorized the convening of the Virginia legislature, as long as it repealed the act of secession and removed Virginia’s armies from the war (which were done). The butler said Mrs. Davis had told him, just two days before, to make the official residence ship-shape “for the Yankees.”

91

90

As he stepped ashore, many African Americans greeted him on their knees and Lincoln helped raise them up, and said “You must kneel to God only and thank him for the liberty you will hereafter enjoy.” Demonstrating that he had never ceased to be the president of the United States, he walked two miles to Jefferson Davis’s office, with security provided by a black regiment, and followed by a large and mainly black crowd of well-wishers, and was regarded from windows with neutral curiosity. He sat in Davis’s desk chair without a hint of triumphalism, asked for a glass of water, and authorized the convening of the Virginia legislature, as long as it repealed the act of secession and removed Virginia’s armies from the war (which were done). The butler said Mrs. Davis had told him, just two days before, to make the official residence ship-shape “for the Yankees.”

91

Apart from Lincoln’s folkloric standing, his pure strategic achievements for the nation are rivaled among his predecessors only by Washington. The Union was impregnable, slavery’s blight and shame had been erased as a bonus to suppressing the insurrection, and the United States was rivaled only by the British Empire and Bismarck’s Prussia as the world’s greatest power, and it had a hemisphere practically to itself. There was no balance of power in the Americas, only American power. Now the United States could receive floods of eager European immigrants, crank up its laissez-faire economy, and swiftly achieve an industrial scale of which the world had never dreamed. Lincoln (and Grant and Sherman) had severed the ball-and-chain from the nation’s ankle, and America could be America, and accelerate toward the summit of the world’s nations.

US Civil War. Courtesy of the U.S. Army Center of Military History

Other books

La página rasgada by Nieves Hidalgo

Mastering Multiple Position Sex by Eric M Garrison

Teddy Bear Sir (The Sloan Brothers Book 3) by Willow, Jo

Tristimania by Jay Griffiths

Bryony Bell's Star Turn by Franzeska G. Ewart, Cara Shores

World's End by T. C. Boyle

When Christ and His Saints Slept by Sharon Kay Penman

Jungle Fever Bundle by Hazel Hunter

Bloody Broken (A Bloody Series Book #2) by Barker, Emily