Read Flow: The Cultural Story of Menstruation Online

Authors: Elissa Stein,Susan Kim

Tags: #Health; Fitness & Dieting, #Women's Health, #General, #History, #Historical Study & Educational Resources, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Women's Studies, #Personal Health, #Social History, #Women in History, #Professional & Technical, #Medical eBooks, #Basic Science, #Physiology

Flow: The Cultural Story of Menstruation (19 page)

The Internet is now an everpresent marketing and advertising outlet for femcare companies. Every major brand now has an ornate Web site full of peppy photos, womanly advice, serious-sounding information, and above all, an underlying sales pitch.

Tampax has a separate Web site for teenagers, full of girlish talk about slumber parties, underwire bras, boys, and (you guessed it) tampons. Even we have to grudgingly admit that their Web site is kind of, well, fun: you can print your own tattoos or head to your dorm room at Tampax U, where you can try on outfits, play with your puppy, and send away for free samples.

At its Web site for teens, Kotex features games, an “attitude explorer” quiz, and message boards, and lets you customize your screen to flower-riffic, groovy green, blue dazzle, or jump ‘n’ roll. The Always Web site lets you create a cyber Zen garden, download recipes for “spoil me choc chip scones” and “caramel nut popcorn delight,” and print out iron-ons for T-shirts. The line between entertainment and advertising is so blurred, there doesn’t appear to be one anymore.

What do you get for the pad that has everything?

—ALWAYS CLEAN AD (2007)

Procter & Gamble Company

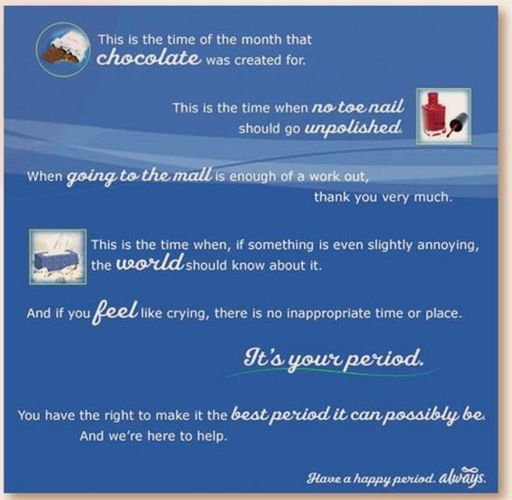

The past two decades have seen new and improved products, with countless items introduced and hawked. Pads with wings. Sanitary wipes. Pearl tampon applicators—a never-ending parade of shapes and sizes. What’s more, femcare companies have also embraced a more positive view of menstruation, even going so far as to encourage women to use their periods as a time for personal indulgence. Yet for all the apparent improvements in both attitude and product development, one disturbing message stays the same: your period is still a secret that should be kept hidden at all costs. By reinforcing this secrecy and the shame that comes with it, menstrual advertising still hasn’t changed one bit after all these years.

Procter & Gamble Company

Procter & Gamble Company

THE SCENT OF A WOMAN

O

NE QUESTION HAS BEEN SERIOUSLY NAGGING us lately Does having your period make you smell bad?

An insanely successful industry has built its mighty foundation on the notion that it does—that the odor is not only appalling and disgusting, but that it must be hunted down and destroyed before it eats away your marriage, your standing in society, your very happiness. Just think of the convictions that may very well be lurking in your own brain this very moment about That Smell: that of course menstrual blood stinks, it’s been sitting around in your uterus for a whole month getting funky! That if you get your period while you’re camping or swimming, bears and sharks will smell you from miles away and immediately come rushing over to eat you! That any civilized male within ten feet will take one sniff of your padded crotch and run for the hills!

And what about the poor old vagina?

Everyone—raise your hand if you’ve had it up to here with those incredibly stupid and unfunny jokes we’ve been hearing since junior high about how bad the vagina smells. Unless there’s something clinically wrong going on down there, do you honestly think you smell like an old mackerel? Or leftover mussels? Or last week’s seafood special at Harry’s Clam Shack?

Nevertheless, the vagina itself has very successfully been treated in advertising as not unlike a kitchen counter, bathtub, or worse: i.e., as a foul, germ-ridden receptacle that needs to be vigilantly cleaned, disinfected, and deodorized before one can even think of having company over. Compare this to one’s nose, where horrifying viruses often do lurk. You wouldn’t think of disinfecting the inside of your nose every time you blew it, would you?

A healthy vagina is, in fact, like the rest of the body—a bustling metropolis full of living microorganisms, most of them friendly, a few not so friendly, all coexisting in relative harmony until something occasionally throws the balance off. You could practically hear businessmen rubbing their hands with glee when they hit on the idea of rebranding this normal state of affairs as a problem that women didn’t realize they had. The vagina, they declared, was in fact not a happy village, but instead, an undesirable ghetto, a breeding ground for germs and disease … and it needed to be cleaned up!

Superficial or apparent cleanliness has become insufficient for the modern woman. The discoveries in the fields of medicine, chemistry and bacteriology have meant a great deal to the health and beauty of womanhood … . The vaginal douche … is now universally recommended as an indispensable part of modern woman’s toilette … !

—ZONITE AD (1925)

In fact, women may well have been splashing water up into themselves since the days of Cleopatra, but the water they used back then wasn’t laced with powerful disinfectants. And what was Zonite, anyway? Sphinx-like, all the advertisers would say was that it was “a colorless liquid that destroys odors and leaves no lasting odor of its own … . In the presence of the natural secretions of the vaginal tract, it has a greater germicidal power than pure carbolic acid.” They added, somewhat ominously, that it could permanently damage clothing, as well.

According to the directions, administering Zonite entailed having to somehow lie underneath eight feet of tubing in one’s bathtub, legs propped up and splayed open like a Thanksgiving turkey, as the recommended two quarts of fluid slowly dribbled downward and up into one’s unsuspecting vagina. If one wanted to attempt this during one’s period, there were even special directions to teach a woman how to deal with those“annoying clots and crustations.”

And if that didn’t make you want to immediately rush out and buy some, the ad went on to point out that Zonite could also be used to clean wounds, to treat sunburn, eczema, poison ivy, and dandruff, and as a mouthwash and underarm deodorant. That’s because Zonite was actually sodium hypochlorite—basically, weak bleach. So why didn’t the manufacturer just come right out and say so? Why the big mystery?

This had much to do with the loosey-goosey approach the government used to take in regulating the manufacture and advertising of drugs and medicine. Attempts had been made earlier in the twentieth century to prevent “filthy, decomposed, or putrid” substances from making their way into one’s canned ham or bottle of celery tonic. Still, federal laws against drug makers not listing their ingredients (which often included things like opium, cocaine, poison, and various radioactive substances) and making truly nutty claims wouldn’t kick in until the late 1930s … and this was only after a new, raspberry-flavored elixir meant to kill streptococcal infections actually killed people instead, due to a poisonous ingredient.

As a result, early advertisers in the feminine hygiene business had no qualms about throwing the net wide with their promises. If no one was going to call you out on your wacky claims, much less nail you on a class-action suit, why not promise the moon? Check out this 1935 advertising booklet for yet another douche: “We all know women whose once pink-and-white complexions have turned to a hard sallowness; who have faded from blooming youth to premature middle age; whose skins are rough, pimply, blotched; who tire too easily; who constantly complain of backaches, headaches and other pains; whose body odors are offensive. Feminine hygiene is indicated as the first corrective of these too customary troubles to which nearly 85 out of every 100 women fall prey.”

Douching was also touted as being good for “congestion in the pelvic region” and the “accumulation of inactive blood in the womb.” And though they might have been accused of gilding the lily, the makers of Certane even thoughtfully bundled up their tubing and nozzles into an attractive gift set.

Even after the FDA finally decided to grow a pair when it came to policing outright charlatanism, douching still continued to be aggressively promoted as the cure for any and all marital ills. After all, wrote Joseph M. Lee sadly in his 1953 book about feminine hygiene, “it is difficult to love that which offends.” In one particularly lurid ad from the 1950s, a distraught housewife pleads, “Please, Dave … please don’t let me be locked out from you!” as she hammers impotently on a closed door festooned with locks and chains labeled “doubt,” “inhibitions,” and “ignorance.” The ad goes on to chide her thusly: “Often a wife fails to realize that doubts due to one intimate neglect shut her out from a happily married love.” Get the hint? She stinks to high heaven, and that’s why she drove poor Dave away! But the real kicker of this ad isn’t just that it’s for any old douche … it’s for (wait for it) Lysol.