Folk Legends of Japan (28 page)

Read Folk Legends of Japan Online

Authors: Richard Dorson (Editor)

Tags: #Literary Collections, #Asian, #Japanese

But the lord did not accept his plea.

THE CAMELLIA TREE OF TAMAYA

Many references are given to Motif Q272, "Avarice punished," which is central the following legend.

Text from

Densetsu no Echigo to Sado,

I, pp. 23-26.

G

EIHA IS

one of the famous beauty spots in Echigo. Especially breathtaking is the view from Tonowa. Below the precipice is a fathomless pool called Zugai-ga-fuchi. According to tradition, there was land all around this place in olden times and the

choja

family called Tamaya lived there.

Tamaya was a merchant family hereditarily dealing in marine products. Tokubei, the head of the family, was an industrious man who worked hard from early in the morning till late at night and amassed much wealth. Many storehouses were built to hold his goods, and he acquired the reputation of being a

choja.

He married a wife as pretty as a flower, and she bore him a lovely child.

Although Tokubei lived in such comfort, yet he was sorely troubled about where to hide his gold and silver. One might say: "In the storehouse," but servants and maids would enter into the storehouse. There was no assurance against a thief's breaking in. Tokubei could not sleep soundly for worrying about the gold and silver which he had secured with such effort. After many sleepless nights he thought of a good plan. There was a bamboo thicket in the back of his house, and a camellia tree grew in that thicket. One dark night Tokubei dug in the ground under the camellia tree, by himself, and buried the box in which he had put his gold and silver. Nevertheless, his heart was not yet at peace. He constantly felt uneasy and in consequence was taken ill.

So Tokubei went with a servant to Matsuno-yama to take the baths. One day, after he had spent about a fortnight there, Tokubei, while in the bathroom, heard someone singing outside:

"The camellia tree of Tamaya at Geiha in Echigo,

The branches are silver and the leaves are gold."

This startled Tokubei. He wondered why in a place so far from his home there should be a person who knew the secret of his burying the gold and silver under the camellia tree. The servant said that the song was sung in admiration of Tamaya's prosperity. But those words did not dispel the fear from Tokubei's mind. He immediately got into a sedan chair and traveled back to Geiha. As soon as he reached his home, he rushed to see the camellia tree in the bamboo thicket. To his astonishment the tree was glittering, with its branches turned to silver and its leaves turned to gold. Tokubei fell into a swoon on the spot.

Through the care of neighbors he came to, but his health was never restored. When his end drew near he told his wife for the first time all about his secret. After his death his wife went out to the bamboo thicket. However, she found the camellia tree appearing as it always had, and she discovered nothing beneath the tree.

THE GOLD OX

The idea of one survivor's being left to tell the story is in De Visser,

The Dragon in China and Japan,

p. igs, in an entirely different legend, about a dragon whose curse killed every person in a clan except one blind minstrel.

Text from

Too Ibun,

pp. 20-22.

A

CHOJA ONCE LIVED

at Otomo-mura in the Tono district of the province of Rikuchu [now Kamihei-gun, Iwate-ken]. A servant in the

choja's

house was a queer fellow. All the year round, during his leisure time, he used to go into the mountains with a spade and dig up the ground here and there to get wild potatoes. People called him a fool. However, one year on New Year's Eve he finally struck a gold deposit in the valley called Hiishi in Otomo-mura. He took a piece of gold to his house and put it in the

tokonoma.

It shone outside through the broken door. So the servant became a rich man like his master and was respected by the people as Komatsu-dono or Komatsu

choja.

Komatsu-dono directed his workers to dig further along the gold vein, and in the third year, again on the day before New Year's, they struck the main deposits, which lay in the shape of an ox. Komatsudono immediately held a great feast outside the pit and spent the night in entertainment. When the New Year's morning sun arose, he performed a ceremony to celebrate the discovery of the main gold deposits. Then he made all the workers pull a brocade rope tied to a horn of the gold ox. With shouts they pulled on the rope, and the horn of the ox broke off with a snap. So they tied the rope around the neck and pulled it, whereupon the ox seemed to move two or three steps ahead; but all at once the pit fell in, killing all seventy-five men.

On that occasion a man in charge of the cooking (whose job it also was to tell the time), who was called Usotoki (False Time) or Osotoki, (Late Time), was also in the pit, having been ordered to help the miners pull the rope. Hearing a call, he let go his hold on the rope and ran out of the pit, but found no one there. Thinking he mistook the voice, he went back into the pit. Then he heard the voice again, and a third time the voice sounded so sharp and urgent that he ran out instantly. The moment he stepped outside the pit it fell in. Therefore Usotoki was the only one who survived the calamity.

People say that this man was very honest, and never served the food before the exact prescribed time. So the workmen ridiculed him by giving him the name False Time.

THE POOR FARMER AND THE RICH FARMER

The popular Motif K1811.1, "Gods (spirits) disguised as beggars. Test hospitality," which appeared on pp. 33-36, recurs here, in conjunction with a common theme of Japanese fictional folk tales, the good old man and bad old man who are neighbors. This and the next two tales show the close line between fictional and legendary traditions. The same story can appear in both forms.

Text from

Ina no Densetsu,

pp. 235-37.

L

ONG AGO

in Yamamoto-mura, a rich farmer and a poor farmer lived next door to each other. One evening a poor dirty-looking bonze came along and asked for a night's lodging at the rich man's house. The greedy old man, on seeing the shabby appearance of the bonze, refused his request with harsh words. The poor bonze was obliged to go next door and make the same request. The poor old man of that house readily gave him a night's lodging, letting him sleep on his only pallet.

The next morning the bonze cordially thanked the old man, saying: "I am really a Buddha who has come disguised as a poor man in order to look into people's hearts in this world. I am very much impressed by your kindheartedness. In appreciation for your goodness I will give you a tree planted in front of your house. You may make anything you wish from it."

As soon as the bonze finished these words he disappeared. Filled with wonder, the old man stood still for a while, without doing anything. Then he beheld a tree rise out from the ground in front of his house, just as the bonze had promised. It grew into a great tree before his eyes. The old man cut it down and made a mortar and a pestle from the wood. When he put rice into the mortar, one quart of rice became two quarts, and when he pounded it, the two quarts of rice became a gallon of

mochi.

The greedy old man next door, observing this, borrowed the mortar and pestle. He pounded his rice, expecting to get many times more

mochi

than there was rice. But strange to say, one gallon of rice in the mortar decreased to two quarts and two quarts of rice to one quart. In his anger, the greedy old man broke the mortar into pieces and threw the pestle away into the brushwood.

When he came to retrieve his mortar, the goodhearted poor man was very sorry to learn of this outcome. Sorrowfully, he collected the pieces of the mortar and made a moneybox from them. In it he dropped the small change from his daily earnings, gained by selling firewood. In the box that money changed into gold pieces, and before long the old man became wealthy.

When the greedy old man heard about this, he forced his neighbor to lend him the moneybox. He took it to his home and put all his money inside it, expecting to take out a heap of gold pieces. To his surprise, however, his money in the box melted into water and, running out as a river, it formed a pool.

So the Hako-gawa [Box River] and Hako-buchi [Box Pool], which still can be seen, gained their names from this story. The place where the greedy old man threw away the pestle is now called Kine-hara [Pestle Meadow].

THE GIRL WHO ATE A BABY

Hearn tells the same basic story as he heard it from Kinjuro, save that the girl who tests the suitors is daughter of a samurai instead of a

choja,

and the corpse is made not

ofmochi

but of the confectionery

kashi

(VI, ch. 25, "Of Ghosts and Goblins," pp. 349-51). Motif H331.1.7, "Contest in reaping: best reaper to get beautiful girl as wife," known in Irish tradition, is present here. The suitor test of cannibalism, which also occurs, is not included in the Motif-Index.

Text from N. Hirano, "Folk Tales from Nanbu Province," in

Mukashi-banashi Kenkyu,

II (Tokyo, 1937), 224-25.

O

NCE UPON A TIME

three young men set out on a journey. They passed fields and mountains and traveled on and on until they came to the gate of a

choja's

house. There they saw a sign which announced that the

choja

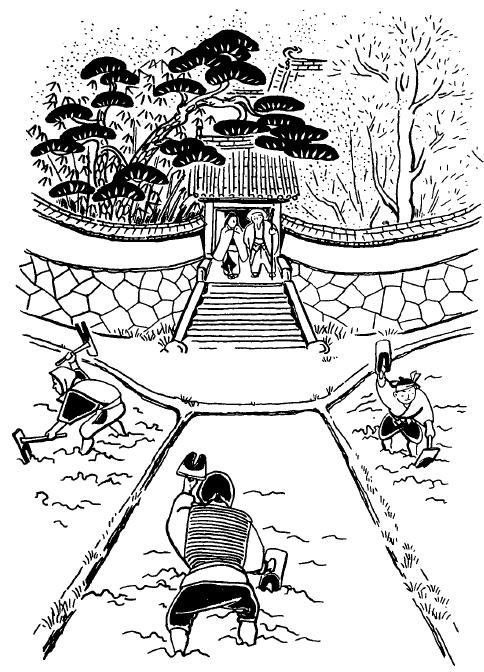

wanted the most able youth in the country for the husband of his daughter.

"This is good news for us. Let's go in and apply," they said and went inside the gate.

The

choja

interviewed them. As they all looked like useful young men, he could not decide which one of the three was superior to the others. So he said to them: "I have a thousand-reap ricefield to the east, a thousand-reap rice field to the west, and a thousand-reap rice field to the front. Each of you shall cultivate one of these fields. And I will see who is the best worker."

Each of the three men was determined to become the

choja's

son-in-law. They had rice cooked in a pot large enough to supply thirty men, and ate it all up. Then they began cultivating the ricefields to the east, to the west, and to the front. An ordinary man might have spent ten days cultivating one such field. These young men, however, each having two forked hoes in both hands, dug up the land so speedily that they finished the work easily in one day. All three returned from the fields at the same time.

"Well, I am extremely surprised at your work today. You three have the same ability. I cannot rank you. May I ask you to stay here for awhile and serve us?" the

choja

said.

The young men willingly agreed to this proposal and stayed on as servants. Quite a few days passed. But to their disappointment, the daughter of the

choja

never appeared to them. They only caught glimpses of her back. So they became very eager to see the girl. One night two of the young men conferred together and then secretly stole into the interior of the house and peeped into the girl's room. There the girl, in white clothes with her hair loosened, had opened the floorboards at one corner. From underneath the floor, she was about to take out a box that looked like a coffin.

Frightened though the young men were, curiosity overcame their fear, and holding their breath, they watched the girl. With a grin on her face, the girl drew a baby's corpse from within the coffin and cut off its arms with a knife. Then she began eating an arm as if it were delicious food. She spoke to the young men, saying: "Will you have some?" And she thrust out toward them an arm dripping blood. The young men were astounded. Far from wishing to become the son-inlaw, they could hardly bear to stay a moment longer in such a place, and they took to their heels that same night.