Fordlandia (27 page)

Authors: Greg Grandin

Tags: #Industries, #Brazil, #Corporate & Business History, #Political Science, #Fordlândia (Brazil), #Automobile Industry, #Business, #Ford, #Rubber plantations - Brazil - Fordlandia - History - 20th century, #History, #Fordlandia, #Fordlandia (Brazil) - History, #United States, #Rubber plantations, #Planned communities - Brazil - History - 20th century, #Business & Economics, #Latin America, #Planned communities, #Brazil - Civilization - American influences - History - 20th century, #20th Century, #General, #South America, #Biography & Autobiography, #Henry - Political and social views

Also unlike the Upper Peninsula, which counted on average about six different tree types per acre, the Tapajós contained about a hundred different species within the same space. Sawyers quickly realized that potentially profitable trees were never grouped together but scattered throughout the forest. And the forest was so thick with trees, climbers, and vines that four or five trees would have to be cut and yanked before a clearing could be made for a free fall. “It cost too much,” remembered one lumberjack, “to get in here and there through the timber to get the kind of wood that was any good. You couldn’t walk ten feet into the woods without cutting your way. It is just a mass of jungle and vines.”

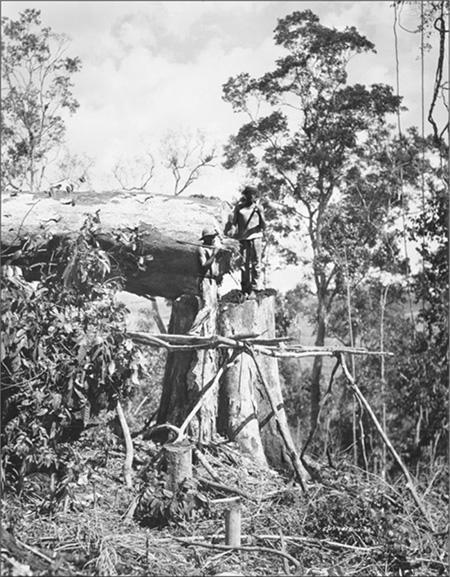

Making a high cut on a big tree

.

So Oxholm began to purchase lumber for his construction needs, which meant that the plantation was not only failing to generate income from timber but actually losing money to purchase it. And since the unsettled customs duty issue made the importation of value-added material expensive, Oxholm had no choice but to buy raw timber in Brazil and mill it at the plantation. He ended up purchasing wood from local indigenous villages. The Ford Motor Company may have been bringing the techniques of centralized and synchronized mass industrial production to the Amazon, but for at least a time it relied on jungle dwellers using little more than crude hand axes to supply its would-be rubber plantation with lumber.

12

At this point, Henry Ford, who had pioneered innovative conservation methods in his timberlands in the Upper Peninsula, intervened directly. He ordered an end to the burning of wood, demanding that logs be milled and stored until “such time as world prices make it salable at this end, and at a profit.” But Fordlandia’s sawyers had little experience storing hardwood in a humid environment, and the sun-dried lumber quickly rotted and warped. Edsel Ford quietly countermanded his father, allowing for the burning of all wood that was “worm-eaten and rapidly decaying.”

13

And Oxholm had no more luck than did Michigan officials enforcing Ford’s “absolutely no tolerance” liquor policy. He tried to evict the “squatters,” as company officials now called titleholders who wouldn’t sell, and to shut down bars and brothels. But faced with what the

New York Times

described as “small uprisings” of machete-wielding protesters, he backed down. Efforts to keep workers off liquor boats also resulted in the threat of “armed resistance on several occasions,” according to Oxholm, who turned to Brazilian authorities for help. But all they did was point out that Prohibition was a US, not a Brazilian, law. They also criticized his hypocrisy since, as they pointed out, the Norwegian captain and his foremen were known to like their drink. Balking at the attempt by Fordlandia’s managers to “apply Prohibition to Brazilian workers without accepting it themselves,” a local magistrate ordered Oxholm to let the liquor boats dock alongside Ford’s property. When plantation managers turned to the itinerant Catholic priest to help preach against drinking, he refused. “For heaven’s sake,” he said, “I’m not a Baptist.”

14

So despite the concerns of Brazilian nationalists who thought that the concession granted too much autonomy to Ford, the plantation found itself caught in a relationship with the rest of the Amazon similar to the one Third World countries often have with the First: extreme dependency. Oxholm depended on a detachment of Brazilian soldiers equipped with machine guns and other arms to keep order. Stuck in the middle of a rain forest yet requiring a steady flow of money to pay workers and suppliers, he depended on the Belém-based Bank of London and South America for twice-monthly cash shipments. Nowhere near close to the standard of self-sufficiency Ford set for his village industries back in the United States, Oxholm depended on Indians who lived along the Tapajós to supply the camp with fish and produce and on local merchants for cattle and other food. Though he had access to a few boats, including a speedy Chris-Craft, to go back and forth to Santarém (and Urucurituba), Oxholm depended on local ancient wood-burning steamers to bring goods and people to the plantation. “The words slow, inadequate, aggravating, etc. hardly express what could be said regarding this matter,” was one Dearborn official’s description of his trip up the Amazon.

15

Over and over, Fordlandia’s managers found themselves reliant on outside support, unable to replicate either the extreme independence pioneered by Ford and Sorensen at the Rouge or the Emersonian ideal of self-reliance embodied in Ford’s community factories and mills.

THE DAY BEFORE he left the estate, Cowling summoned its staff and “lectured them severely for their lack of organization and efficiency.” He was harsh on Oxholm, whom he found overbearing and arrogant and unwilling to offer direction to his managers and foremen. Cowling condemned the lack of organization that had produced “waste of various kinds which is appalling.” With no leadership or plan for moving forward, the plantation’s foremen, he said, were turning in circles. On numerous occasions during his short stay, Cowling had seen four or five members of the staff deep in conversation for extended periods of time over matters of relatively little importance, and even then they often didn’t come to a decision about what to do next.

“Many things,” Cowling scolded Oxholm, “are begun and then not followed up and to say that your entire operation is costing at least fifty percent more than it should is putting it mildly.”

16

Cowling urged the Norwegian captain to act in a way that would repair the “moral reputation of the Ford Motor Company” and to live up to a “higher sense of duty to the Company as well as a keener idea of personal responsibility in your work.” “You are a long ways from your old home, but you must carry on just as if the eyes of the home office were upon you.”

The home office, in fact, never took its eyes off Oxholm, and Sorensen followed up Cowling’s visit by firing off cable after cable demanding an accounting.

“Do you yourself use intoxicating liquors of any kind?” Sorensen asked Oxholm. “Have you any intoxicating liquors in your possession, either in your home or elsewhere on our property? What was the trouble on this liquor question? What about conduct of other officials of the company with reference to this same question that I applied to you? Do any of them use intoxicating liquor? What is the reason for this long delay in answering letters?” Sorensen ended this barrage demanding immediate answers “without any evasion.”

17

Oxholm had had enough. His sister Eleanor and wife, Cecile Hilda, had joined him toward the end of 1928, along with his son Einar and three daughters, Mary, Marcelle, and Eleanor. By the end of 1929, three of his children—Einar, Mary, and Eleanor—had died in an epidemic of an unnamed fever. In early 1930, a second son, also named Einar, died at birth. Sorensen’s cables grew increasingly shrill, but by then Oxholm had stopped replying to them. In May he either quit or was fired—company records are silent on the matter—boarding the

Ormoc

, along with his brokenhearted wife and their surviving daughter, Marcelle, to sail back to the United States. Upon arriving in New Orleans, he continued on to Dearborn, where he met with Henry Ford, debriefing him on the rubber plantation and asking if there was another ship he could captain. Ford said no, and Oxholm returned to New Orleans to once again work with the United Fruit Company.

Fordlandia, Oxholm would later say, was “the hardest proposition I have ever tackled in my life.”

18

WILLIAM COWLING LEFT Fordlandia in late September for Rio and sailed for Dearborn on October 2. A request from a

New York Times

reporter for an interview before he left was met with refusal, which the paper “interpreted as indicating he found conditions discouraging.” Though he had managed to establish some goodwill in Rio, negotiate a compromise on the issue of export taxes, and identify what the problems were in Fordlandia, other troubles persisted. Governor Valle continued to refuse to read the concession as giving Ford the right to expropriate the property of settlers who wouldn’t sell. Nor would he force Francisco Franco, the merchant patriarch of the island of Urucurituba, across the river from Fordlandia, to part with Pau d’Agua, the small village that the Ford Motor Company felt had become the source of much of the plantation’s vice. And while the import duty issue was supposedly settled through the intervention of Ford’s Rio representative, customs inspectors at Belém were still holding up material that they deemed unrelated to the “refining of crude rubber or the manufacture of rubber products.”

19

Then the company’s fortunes received an unexpected boost. In October 1930, a revolution brought Getúlio Vargas to power. Vargas, a reformer who would dominate Brazilian politics for the next two decades, creating the modern Brazilian welfare state, is often compared to Franklin Delano Roosevelt. The Vargas government passed labor legislation, regulated the financial sector and other areas of the economy, and generally presided over the strengthening of the central government. In the United States, Ford would come to detest FDR and his New Deal for implementing many of the same policies. Yet in Brazil, Vargas’s ascension meant mostly good news for Ford, as it signaled the end of the excessive federalism that had the Ford men tied in knots trying to address problems in Belém, Manaus, and Rio.

The ripples of the revolution were immediately felt in the state of Pará. Though the revolutionaries were nationalists and therefore suspicious of foreign capital, they were also modernizers, hostile to the regional oligarchs who ruled each state as if it were their own personal fiefdom. Ford posed a particular conundrum. He was both a modernizer, promising to bring capital-intensive development to the backwater Amazon, and a man who wanted to run his namesake property with sovereign autonomy, like the rubber lords who didn’t like Rio meddling in their affairs. Vargas cut through this dilemma. Soon after coming to power, he replaced Valle with someone sympathetic to Ford. He also confirmed Ford’s land concession, a good sign considering that he canceled all foreign contracts in Pará except for Ford’s and one other. It took somewhat longer to resolve the sundry tax issues, as Ford lawyers continued to debate with officials how to interpret the minutiae of Brazil’s custom tax law. Eventually, in a series of decrees in 1932 and 1933, Vargas granted Fordlandia its long-sought import and export duty exemptions—retroactively, which was key since by the time of Vargas’s dispensation the company, according to Cowling, had a “couple of million dollars charged” against it.

20

For the foreseeable future, Ford could count on a relatively supportive government and a predictable tax structure.

21

CHAPTER 13

WHAT WOULD YOU GIVE

FOR A GOOD JOB?

HENRY FORD, EVER READY TO CHALLENGE COMPANIONS TO A foot race or a fence-jumping contest, represented, as both icon and huckster, the freedom of movement that distinguished American industrial capitalism from its European equivalent. “All that is solid melts into air,” Karl Marx wrote in the middle of the nineteenth century to describe the revolutionary potential of capitalism to break down feudal hierarchies and the superstitions that justified them. But Europe took a considerably longer time to thaw than the United States: in no other country had national identity become so closely associated with movement—whether horizontal, that is, the march west and then overseas, or vertical, the idea that those born to the lowest ranks could climb power’s peaks.

There would be inventors of faster machines than his motor car. Yet nobody could claim to have transformed, at least in such a noticeable way, nearly every realm of daily life, from the factory and field to the family. And for capitalism’s sake he did so in the nick of time. Just as industrial amalgamators like John D. Rockefeller were declaring that “the age of individualism is gone, never to return,” Ford came along to put the car—a supreme symbol of individualism—in reach of millions. “Happiness is on the road,” Ford said. “I am on the road, and I am happy.”

Ford peddled change as if he were the head not of a motor company but of the Metaphysical Club. “Life flows,” he remarked in his cowritten autobiography. “We may live at the same number on the street, but it is never the same man who lives there.” The myth, of course, didn’t come close to matching the reality, for what some came to call a “new industrial feudalism” intensified existing prejudices and created new forms of exclusion and control, including those perfected by Ford himself. “The Ford operators may enjoy high pay, but they are not really alive—they are half dead,” mourned the vice president of the Brotherhood of Electrical Engineers in 1922. Ford responded by justifying his antiunionism not in the language of reaction or even primarily in that of efficiency but rather by assigning to it the essence of true “freedom”: “The safety of the people today,” he said, also in 1922, is that they are “unorganized and therefore cannot be trapped.” But if most of his employees had been reduced to cogs in the greater machine called Fordism, for a few mobility was more than a promise.

1