Fordlandia (31 page)

Authors: Greg Grandin

Tags: #Industries, #Brazil, #Corporate & Business History, #Political Science, #Fordlândia (Brazil), #Automobile Industry, #Business, #Ford, #Rubber plantations - Brazil - Fordlandia - History - 20th century, #History, #Fordlandia, #Fordlandia (Brazil) - History, #United States, #Rubber plantations, #Planned communities - Brazil - History - 20th century, #Business & Economics, #Latin America, #Planned communities, #Brazil - Civilization - American influences - History - 20th century, #20th Century, #General, #South America, #Biography & Autobiography, #Henry - Political and social views

Yet there’s something more Mark Twain than Joseph Conrad, more Huckleberry than homicidal, about the stories of Ford men lost in the wilderness. Consider Mr. Johansen, a Scot, and Mr. Tolksdorf, a German, dispatched to gather rubber seeds in September 1929 by Ford’s envoy William Cowling. Their mission was urgent. After the disaster of Captain Oxholm’s first planting, the two men were charged with locating groves of high-yielding rubber trees, gathering their seeds, and returning in time to plant them by the coming May, before the rains ended. Traveling with a Brazilian assistant named Victor Gil and a “Negro cook” named Francisco, the two Europeans cut loose their Brazilian underlings a month into the trip. Gil they abandoned in a two-hut village, and Francisco they put ashore on an uninhabited island.

1

Johansen and Tolksdorf headed to Barra, a small rubber town at the headwaters of the Tapajós. With the idea that it would be “nice to have a highball or two” on the coming New Year’s Eve, they ordered wine, whiskey, and beer and paid for it with company funds. They proceeded to get “intoxicated and remained that way most of the time throwing money away and making fools of themselves in general.” One night, Johansen stumbled into a trading post, where he purchased several bottles of perfume. He then headed back out to the town’s one street, swerving back and forth as he chased down cows, goats, sheep, pigs, and chickens. Baptizing the livestock with the perfume, he repeated the benediction “Mr. Ford has lots of money; you might as well smell good too.”

After about a week, the two renegades contracted a launch, loaded it with Ford-bought whiskey and a prostitute they hired as a cook, and set off on what sounded more like a “vagabond picnic than a rubber seed gathering expedition.” They continued their riverine ribaldry from village to village, one smaller than the next, until they landed in a government area set aside for the Mundurucú Indians, centered on a Catholic Franciscan mission. There Johansen established himself as the “rubber seed king of the upper rivers,” using a crew of about forty Indians to clear underbrush and gather seeds.

FORD MANAGERS, LIKE European colonialists in Asia and Africa, were fixated on race. Ernest Liebold, after all, advised Ford to plant rubber in Brazil and not in Liberia largely because of his low opinion of Africans. “She has just a touch of the ‘tar-brush,’ ” wrote O. Z. Ide in his diary after meeting the Brazilian wife of a Belém-based British exporter. Others who followed Ide used the words

nigger

and

negroes

freely and, according to historian Elizabeth Esch, plotted workers by skin color on a spectrum that ranged from “tameness” to “savagery.” When Archibald Johnston, who would shortly become Fordlandia’s manager, wanted to send Henry Ford and other company executives some samples of rain forest wood, he had a “little wooden nigger boy” made from different specimens of trees found on the estate. Johnston said in a note accompanying the gift that its color was “all natural.” Its cap, coat, teeth, and collar were made of pau marfim, a dense, cream-colored wood. Its head was carved from pau santo, a kind of tonewood. And the buttons were pau amarelo, or yellowheart. Ford’s secretary thanked Johnston for the “nigger boy,” saying that his boss was “very pleased” with the gift. “It is indeed a fine piece of work,” Sorensen replied directly.

2

Yet instead of unleashing the kind of mortal racism that gripped Kurtz, the jungle seemed to catalyze in Ford men another trait endemic to Americans: a blithe insistence that all the world is more or less like us, or at least an imagined version of “us.” Here is the sawyer Matt Mulrooney commenting on workers, many of whom in the United States he would have undoubtedly considered black:

Most of the people are white people. They are as white as we are. They are not colored up. Once in while you would run across a fellow and you could see he was smeared up with some other nationality. I wouldn’t say it was Irish, or English, or Scotch or Dutch. I don’t know what it was, but he’d have a different color on him. You couldn’t tell. There was a color there. He wasn’t a smokey or a white face. Them are the best workers. The rest of the 3,300 people were all the same, all white generally, they are all white, sunburned or tanned.

Nor were the Ford men seduced into thinking about the natural wonders of the Amazon in existential terms as markers of evil or human progress—as were so many travel writers. For Theodore Roosevelt, who valued the rough frontier or jungle life as character building, the Brazilian rain forest was simultaneously empty of the moral meaning created by civilization’s advance and a cure for its corruption. But the men Ford sent down to build Fordlandia, and the women who went with them, largely avoided such musings. They did occasionally make mention of the tropical flora and fauna, yet often in the most prosaic way, commenting on the size of the bugs or the relentlessness of the heat and rain, and usually in mundane comparison with what they knew back in the States. Two decades after Constance Perini returned home, what still impressed her the most were the “black ants with claws just like lobsters” and the “largest flying cockroaches I’ve ever seen”—or, she said, “at least they looked like cockroaches.”

3

Charged with transforming the jungle into a plantation, company managers were of course concerned with the Amazon’s natural dimensions. They had to consider many variables—quality of the soil and level of the land, irrigation, potential for hydropower, density of mosquitoes—when choosing where to plant rubber, where to build the workers’ settlement and town center, and where to place the factory and dock. Dearborn sent a steady stream of questions to determine what equipment to ship: “What is the general tenacity of attachment of vines to trees and can they be readily pulled away from trees with heavy tractors or with a Fordson tractor?” “Is nature of soil such that trees will cling tightly to soil and carry a large portion of soil with roots if pulled up with tractors, or is soil loose and free enough to allow trees to be pulled out without leaving large holes which will require backfilling?” “What percentage of trees will be suitable for logging?” “What would be the cost of logging over 1000 board feet using native hand labor without machinery?” “Ascertain sources, quality and quantity of stone, gravel and sand for concrete. Crushing strength and chemical composition of clean sharp sand, gravel, and limestone should be determined.” But the managers answered these questions with an unimpressed prose, unlike the kind of florid verse that the Amazon usually provoked.

4

The jungle tended to produce not apocalyptic reflections on man’s place in the universe but rather a wistful homesickness, a constant comparison of the Amazon with Michigan. Mulrooney got a “big kick” when, upon his return to Michigan, his friends would say to him, “Oh, gee, Mulrooney, it must have been a wonderful place to fish and hunt, all woods.” “Yep, fine place,” he told them, “you couldn’t get out in the woods to hunt. If you caught a fish, it wasn’t any good. They were just a bunch of grease. Give me the fish in Michigan!” Whether Ford managers, engineers, and sawyers may have thought the jungle a gothic hell or a window on to the consuming indifference of the primeval world to the hurriedness of man, they mostly kept it to themselves. When they looked up and saw vultures, as O. Z. Ide did upon arriving in Belém for the first time, they thought of Detroit pigeons.

IF JOHANSEN AND Tolksdorf were comical Kurtzes, they were pursued by their own Michiganian Marlow, John R. Rogge. An “old time lumberjack” and a “natural born mill man” from the Upper Peninsula, Rogge had been at Fordlandia since the first tree was felled in early 1928, having been sent by Henry Ford to join Blakeley’s advance team. Since he had survived with his reputation relatively intact both the opportunism of Blakeley and Villares and the ineptitude of Oxholm, Cowling, before he left the plantation, named Rogge assistant manager and told him to keep an eye on Oxholm.

Rogge was in a staff meeting when Francisco, the marooned cook, showed up at the office with a tale straight out of a “dime novel.” It was night when Johansen and Tolksdorf put Francisco on shore, and he didn’t realize until morning that he was on an uninhabited island. To stay meant to starve, so he lashed some driftwood together and floated a full day downriver until he came upon the hut of a rubber gatherer, who gave him some food and shelter. He then bargained for a canoe, taking twenty-four days to reach the Ford plantation, “through dangerous rapids, tropical rains, and all of the hazards of travel on the Upper Tapajós.” After a short discussion among the staff, Rogge decided that the procurement of usable seeds was a top priority and that he would head an upriver expedition to search for the two wayward Ford agents.

5

Rogge was happy to go. Born on a Wisconsin farm in Langlade County, he was one of nine boys, three of whom moved to northern Michigan to look for work in the timber industry. He felt at ease in the Tapajós valley, which, like Michigan’s vast forests, was sparsely populated. If the Amazon was hot and humid, the eastern Great Lake plains of the Upper Peninsula were similarly swampy and moist and made miserable by horseflies and other insects during a good part of the summer. Rogge was also used to organizing life and work around the change of seasons: most of Upper Peninsular logging was done in the winter, when the cold hardened the roads and froze the swamps, allowing easier access into the forest. And he was no stranger to water transport: Like the Amazon, the remote Upper Peninsula was cut through with rivers, which before the arrival of the railroad served as the main arteries for loggers, who built camps on their shores.

6

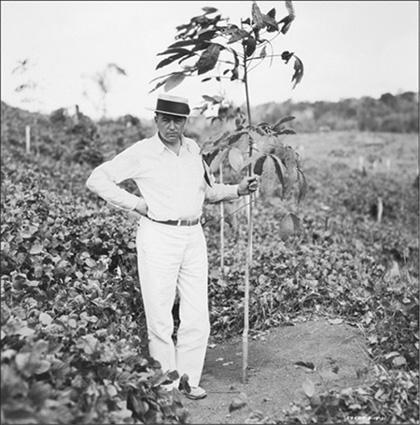

John Rogge with young rubber tree

.

Rogge thought his “sleuthing of a Scotchman” and “a German” would allow him to escape the familiar routine of the work camp and leave behind the relatively unimpressive lower Tapajós for the real Amazon. Northern Wisconsin, where he grew up, is steeped in Native American culture and history. Yet by time the “American lumberjack,” as Rogge described himself, came of age in the early twentieth century, Great Lakes Indians like the Potawatomi, Menominee, and Ojibwa found themselves struggling to survive, victims of population decline, forced removal policies, and coerced assimilation. Rogge, therefore, hoped that his trip would provide an opportunity to encounter true Indians, of the kind that lived in the “real, untouched jungle.” He gathered a team together, including a few Brazilians who knew something about seeds, and outfitted a small steamboat—open to the weather except for a small thatched sleeping cabin—with a two months’ supply of food and equipment. As they set off from Fordlandia, Rogge and his men made the most of what anthropologist Hugh Raffles has called “hospitality trails,” routes long used by European and American explorers, scientists, and businessmen as they traveled around the Amazon. On these routes, native labor did the hauling, cooking, cleaning, and poling (when rapids prohibited the boat’s passage), and planters, merchants, town officials, and priests provided shelter and sustenance.

7

Rogge was impressed with the skill of his barefoot and naked-to-the-waist boatmen, who occasionally had to jump overboard to push his boat through fast-moving water. He was less enthusiastic about his cook, also barefoot and dressed in a “pair of pants and a jacket that were so greasy and dirty that they interfered with his every movement on account of their stiffness.” Rogge ordered him to put on clean clothes and to keep the cooking area neat and orderly, which he did, though he never learned to prepare eggs to the lumberjack’s taste.

ROGGE LEFT FORDLANDIA in early December 1930, traveling during the last stretch of the rubber season, the six-month dry period when latex is tapped, smoked, and sent downriver. He passed riverboats and canoes taking balls of rubber to trading posts. He slept in the houses of local merchants and traders and negotiated with local tappers to allow his crew to string their hammocks around the trappers’ huts. All of this gave him a firsthand view of the river’s rubber economy.

As in other areas of the Amazon, rubber trees were not planted but rather grew wild along the 1,235-mile Tapajós, particularly in its upper headwaters and floodplains. Making his way to these thick, rubber-rich groves, Rogge found that the sloping banks framing the river’s wide lower reaches gave way to forbidding jungle overhang. Within a few days upriver of Fordlandia, the jungle became dense and the Tapajós narrowed to a gap, flanked by limestone cliffs and dotted with tree-filled islands. The river then climbed over a series of white-water torrents and falls that only low-draft boats, light enough to be poled, pulled, or dragged overland, could travel. For the first couple of decades after the 1835 Cabanagem Revolt, when the rubber trade took off, these obstacles had discouraged commercial exploitation. A Frenchman who made this trip in the early 1850s described “roaring and terrible” rapids that “cross and recross and dash to atoms all they bear against black rocks” guarding the “deep solitudes” of the upper Tapajós. Yet by the 1870s, the diminishing yield of

Hevea

around the mouth of the Amazon, combined with increasing world demand, prompted merchants and traders to push farther and farther into the valley, avoiding the rapids and falls by building portage paths through the jungle. In the early twentieth century, most of the upper Tapajós latex trade was dominated by one man, Raymundo Pereira Brazil, whose family had migrated to the region from the state of Minas Gerais. At the height of the boom, Brazil owned two thousand rubber

estradas

, or trails. He controlled the river’s workforce through debt bondage and monopolized trade and transportation routes.

8