Fordlandia (43 page)

Authors: Greg Grandin

Tags: #Industries, #Brazil, #Corporate & Business History, #Political Science, #Fordlândia (Brazil), #Automobile Industry, #Business, #Ford, #Rubber plantations - Brazil - Fordlandia - History - 20th century, #History, #Fordlandia, #Fordlandia (Brazil) - History, #United States, #Rubber plantations, #Planned communities - Brazil - History - 20th century, #Business & Economics, #Latin America, #Planned communities, #Brazil - Civilization - American influences - History - 20th century, #20th Century, #General, #South America, #Biography & Autobiography, #Henry - Political and social views

At the end of 1931, Johnston built an open-air dance hall where the plantation held, at Henry Ford’s urging, traditional American dances. Back in Michigan around this time, Ford, as part of his broader antiquarianism, began to sponsor fiddling contests and sent agents to scour the nation to record the steps of traditional dances before they disappeared or were corrupted by the “sex dancing” that was sweeping America. He also established his own private record label, Early American Dances, and hosted balls in Dearborn and in his growing collection of inns, farmhouses, and village industries throughout the country. Employees understood invitations as “thinly disguised commands” to attend, and they did their best to maneuver through waltzes, polkas, minuets, square dances, as well as the quadrille and the ripple. All guests—even Harry Bennett, who liked to wear bow ties so that in a fistfight his opponent couldn’t get a hold on him—were expected to follow proper decorum: men, not women, were to initiate the dance and there was to be no cutting in and no crossing the middle of the dance floor. Benjamin Lovett, the instructor Ford contracted to organize these balls, wrote in his

Good Morning: After a Sleep of Twenty-Five Years, Old-Fashioned Dancing Is Being Revived by Mr. and Mrs. Henry Ford

, published in 1926, that protocol dictated that the man was to guide the woman without embracing. There would be no bodily contact except for the thumb and forefinger, which were to touch the woman’s waist as if “holding a pencil.” Boxes of the book were shipped up to Ford’s towns in the Upper Peninsula, to Alberta, Pequaming, and other villages, where for a time the local schoolchildren took daily dance classes.

16

In his encomium to Ford’s music patronage, Lovett linked specific dances to “the racial characteristics of the people who dance them.” Modern American dancing, with its flappers moving to the fox-trot, shimmy, rag, Charleston, and black bottom, not to mention the obscenely sensuous tango, had been sullied by influences “that originated in the African Congo, dances from the gypsies of the South American pampas, and dances from the hot-blooded races of Southern Europe.” But Ford was rescuing a truer tradition of dance that “best fits with the American temperament, . . . a revival of the type of dancing which has survived longer among the Northern peoples.” Ford himself traced the rot not to Africa, Argentina, or Italy but to Jews. The

Independent

, during its run of anti-Semitic articles, complained that the “mush, the slush, the sly suggestion, the abandoned sensuousness of sliding notes are of Jewish origins.”

17

Ford’s dance revival clearly reflected his conservative turn. As the historian Steven Watts writes, the industrialist “deployed swirling, waltzing couples and stamping square dancers as skirmish lines in a larger cultural campaign to reclaim and defend American values and practices from an earlier day.” Fordlandia allowed Ford to go on the offensive, to advance his campaign into the Amazon and reclaim its inhabitants, some of them already under the sway of dances like the Charleston, for a more virtuous sociability. In the rain forest, Ford made his counterthrust against Jazz Age culture not only with dance but also with verse. The man many the world over blamed for “trampling down individuality, beauty, and serenity, and erecting machine altars to Mammon and Moloch” sponsored in Fordlandia readings in Portuguese translation of Emerson, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and, ironically, William Wordsworth, the poet who declaimed against the mechanical “fever of the world” leading a “rash assault” on English greenery.

18

IN ADDITION TO buying soccer balls to keep workers busy, Captain Oxholm also asked Charles Sorensen to send him a “moving picture outfit.” Sorensen did, and Fordlandia began to screen films. But the projector the Rouge sent down was outdated and the movies available from Belém’s distributor were old, “terribly scratched, warped and dried out.” And workers complained of boredom if the same picture was screened too many times. When Johnston took over management, he secured a better sound projector, which allowed him to feature more up-to-date films. He found a Fox agent in Recife who could supply the plantation with B action pictures, the “type that is best liked down there,” said Johnston. Rio’s movie industry was just getting started in the 1930s, and Johnston tried to show Brazilian films whenever he could, especially the popular

chanchadas

, slapstick musicals, including a few starring a young Carmen Miranda. “We intend putting on a good show for our workers,” Johnston said. It’s unknown if he ever had the opportunity to screen

Law of the Tropics

, a Warner Bros. picture partly based on a 1936

Collier’s Weekly

article on Fordlandia. The film, released in 1941, was a bust in the United States, panned by the

New York Times

for unrealistically depicting a “verdant” jungle where “mosquitoes never bother any one.”

19

Fordlandia dance hall, with movie screen on back wall

.

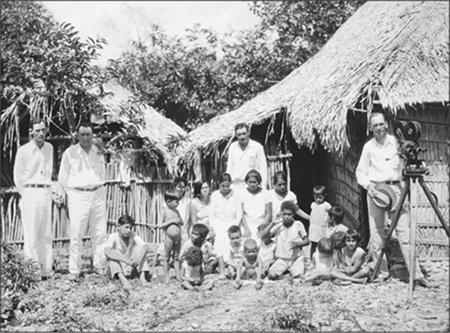

“We intend putting on a good show”: John Rogge, second from left, Curtis Pringle in the middle, and James Kennedy with camera, filming scenes of family life

.

Fordlandia also put on a good show for Dearborn. By the 1930s, Henry Ford had embraced celluloid as a way to link together his far-flung empire. Film crews would document his camping trips with Thomas Edison, Herbert Hoover, and John Burroughs; aerial shots of Mexico; scenes of street life in Bridgetown, Barbados; Diego Rivera painting the Detroit Institute of Arts; surgeries in the Henry Ford Hospital; Ford mines, mills, and dams; and each and every subassembly process that went into making a Ford car. Fordlandia, too, was filmed, as a decision was made early to “build up a complete history of our development in detail,” for “a ready reference to any given operation.” Henry Ford specifically asked to see “action, pictures, etc. etc.” of Fordlandia’s garden program.

20

Johnston sent roll after roll of raw 16 mm footage to Dearborn, to be screened for officials, including Henry and Edsel, so they might get a sense of the plantation’s progress and everyday life. These reels were largely made up of random, uncaptioned images: men sawing trees and clearing jungle, Americans shooting caimans and gutting manatees, chunks of meat dangled in the river to provoke a piranha frenzy, lingering head shots of workers, who seemed to have been chosen to illustrate the region’s racial diversity, schoolchildren listening courteously to their teacher, and workers lining up to receive their paychecks, undergoing a medical examination, or playing soccer as women and children looked on. Many of these images were folded into in-house documentaries detailing different facets of Ford’s vast holdings or into films focused on latex, such as

Redeeming a Rubber Empire

. In exchange, Dearborn sent news and documentary shorts down to Fordlandia, familiarizing Brazilian workers with other branches of the Ford family.

New Roads to Roam

and

Streamlines Make Headlines

introduced them to the Lincoln Zephyr, a luxury car made by a company Ford purchased in 1922, and let them know they were living in a new, aerodynamic age.

Making Wooden Wheels for Autos

gave the estate’s residents a picture of the Rouge’s state-of-the-art machinery that made the spokes and rims that would soon be framing tires made from Fordlandia latex.

Dearborn also provided films capturing the age of discovery, which was largely made possible by the rapid advances in transportation technology. Fordlandia workers and managers watched

Bottom of the World

, about Admiral Richard E. Byrd’s expedition to Antarctica, a “rare, unbelievable record of the strangest and queerest things on earth” in which “not a scene” was staged (Byrd, partly funded by Edsel, named a mountain range after his patron).

Some Wild Appetites

let them enjoy “monkeys, alligators, tortoises, otters, opossums disporting themselves at feeding time.” And

Hell Below Zero

took them to central Africa on an expedition commissioned by the Milwaukee Museum in search of the legendary Mountains of the Moon, a snow-capped 16,000-foot-high range separating what is today Uganda and the Democratic Republic of Congo. Deep in the sweaty sea-level Amazon, clackity film projectors beamed onto an outdoor screen the “fantastic sight of natives shivering before a campfire on the mythical line of the Equator.”

21

A whole set of films featured the heroism not of explorers but of Ford’s cars, which could put the most remote places within the imaginative reach of the common man. Increasingly after World War I, newspapers reported on global expeditions that tested the endurance of the Model T. How far into the Amazon could it penetrate, how far up Machu Picchu could it climb?

Ford News

, an in-house paper for company employees, regularly ran stories about the adventures of the T along the Inca Highway or into the Mayan jungle. If Ford’s car could make it, then anyone could, and so the age of exploration gave way to the age of tourism. In Fordlandia, in addition to documentaries about expeditions to the South Pole or up the Mountains of the Moon, the estate screened Ford-produced films such as

Yellowstone National Park

and

Glacier International Park

, promoting automobile leisure travel and introducing plantation workers to America’s natural wonders, accessible as never before thanks to Ford.

Most of the company’s historic film stock is stored in the United States National Archives in Washington, D.C., and judging from the sharp juxtapositions of otherwise unrelated shots—footage detailing, say, the synchronous industrial choreography of the Rouge followed by a bucolic panorama of farm life, or scenes illustrating the glacial pace of rubber tapping preceding images of dizzying assembly lines and conveyor belts—Ford officials and managers seemed to revel in contrasting the primitive with the modern, which highlighted their role in speeding up the world. In early 1928, for example, the

Ford News

ran a story reporting on a momentous event: the world’s first in-flight movie. Outfitted with a projector and screen, a Ford TriMotor, the first mass-produced metal-clad airplane, took off from a Los Angeles airfield with curtains drawn as eight “theatrical people” settled into comfortable wicker chairs. The movie selected for the occasion, Harold Lloyd’s

Speedy

, was a sly choice. Unlike Charlie Chaplin’s later

Modern Times

, which offered a dark critique of Depression-era industrial speedup, Lloyd’s movie is a Jazz Age celebration of the velocity of modern life. The plot of the film involves Lloyd’s fighting not to save Manhattan’s last horse-pulled tram but to make sure its owner gets a good price for selling his route to a motorized trolley monopoly. As the Ford TriMotor circled over Los Angeles, its passengers probably laughed at the opening scene of a tourist guide pointing out a “vehicle that has defied the rush of civilizashun—the last horse car in New York.”

22

* * *

ON THE TAPAJÓS, Johnston had finally succeeded in replicating a shiny American town, with neat houses, clean streets, shops, and a town square. It was, one traveler said, a “miniature but improved Dearborn Michigan in the tropical wilderness.” He even managed to re-create some of the social conventions of Main Street America, at least as Ford imagined them, with weekly dances, movies, and other forms of recreation, including golf courses, tennis courts, swimming pools, and gardening clubs. Fordlandia paid good wages, provided decent benefits, including health care, and tried to cultivate virtuous workers. Yet Johnston was still finding it hard to usher in Ford’s vision of modern times. In Dearborn, Ford’s famed paternalism was diluted by the diverse resources available to workers in an urban, industrializing society. But in the Amazon, running a remote plantation with impoverished labor in a hostile environment, Fordlandia’s managers found themselves presiding over an extreme version of cradle-to-grave capitalism—literally.

23