Fordlandia (44 page)

Authors: Greg Grandin

Tags: #Industries, #Brazil, #Corporate & Business History, #Political Science, #Fordlândia (Brazil), #Automobile Industry, #Business, #Ford, #Rubber plantations - Brazil - Fordlandia - History - 20th century, #History, #Fordlandia, #Fordlandia (Brazil) - History, #United States, #Rubber plantations, #Planned communities - Brazil - History - 20th century, #Business & Economics, #Latin America, #Planned communities, #Brazil - Civilization - American influences - History - 20th century, #20th Century, #General, #South America, #Biography & Autobiography, #Henry - Political and social views

Hundreds of babies were born each year in Fordlandia, creating a whole new set of problems for its managers. Amazon residents were used to giving birth at home under the care of a midwife. Ford doctors frowned on the practice, yet did not want to tie up hospital beds for obstetrics. So they didn’t push the issue until a woman died in childbirth in late 1931. From then on, medical and sanitation squads added a new responsibility to their ever growing list, as they checked women for pregnancy and made sure no illicit midwifery was taking place.

Once born, children needed care. Dr. McClure had hopes that Dearborn chemists would soon find a “satisfactory substitute for cow’s milk with soy bean milk” that could be used to feed infants and toddlers. But until then, Fordlandia’s hospital distributed Borden’s Klim, a powdered whole milk, to new mothers. The staff quickly learned that utensils had to be provided as well, since most workers didn’t own dishes, or “even a spoon,” to prepare the powdered milk, using instead their fingers to mix the powder in empty cans. Before long the plantation, on instructions from Edsel, had established a day-care center, named after Darcy Vargas, President Vargas’s wife. Working mothers could leave their children in the care of company nurses, under the supervision of doctors who made daily visits. Johnston complained that the center “cost considerable money to operate.” Children also needed to be educated, and before long the company was running seven schools in the Amazon, named after Ford’s son and grandchildren, teaching home economics for girls and vocational training for boys, and gardening and ballroom dancing for all. “Shades of Tarzan!” ran the caption under a photograph of children in a company brochure celebrating the plantation. “You’d never guess these bright, happy healthy school children live in a jungle city that didn’t even exist a few years ago!”

24

Despite such cheery publicity, children on the Tapajós, including many who lived in Fordlandia, continued to suffer. Malnutrition remained one of the plantation’s most obdurate problems. “The cemetery,” McClure reported to Edsel, “contains children’s graves far in excess of adults.”

After the December riot, Dearborn attempted to hire more married than single men, with the idea that men with families would be less transient and more dutiful. But married men often trailed behind them not just a wife and a few children but an extended network of relatives, ever in danger of becoming wards of Ford’s largesse. “These

caboclos

,” wrote Johnston, “all seem to have a lot of hangers on.” To discourage them from coming to Fordlandia, he suggested that they be provided with nothing “other than food.”

Johnston was finding it difficult to abide by his own judgment. He tried to cut off commissary credit to the wife of an injured worker laid up in the hospital, since she was using the food she purchased on the credit to feed her extended family of three cousins and three nieces and to prepare meals for sale to unmarried workers. But when Johnston went to speak with her, she pleaded hardship. “God only knows my worries,” she told the engineer. The “poor woman is probably correct,” Johnston admitted, fearing that if he cut her off her immediate family would go hungry. He relented. “It is hard to know where to stop,” he said. “We take care of all cases which actually need help.”

Workers were still dying, leaving widows behind. “Widow Francisca Miranda” was an “old timer” who has “caused plenty of trouble” for the staff, insisting that she had the right to tap Fordlandia’s wild rubber trees. Johnston concluded it was probably “easier” just to give her some money. And there remained the issue of burials, which the company still paid for, though it did try to pass off responsibility for the cemetery to Santarém’s Catholic bishop. But the bishop’s priests were stretched thin throughout the Tapajós valley, and he was already annoyed that Fordlandia refused to place its schools under his authority or pay for the construction of a proper church. So he demurred, consenting only to have his clerics occasionally pass through the plantation to say mass and minister the sacraments. Without a resident priest, Fordlandia would have to continue to bury its own dead.

25

All these social problems, though, would pale beside the one looming just ahead with nature.

CHAPTER 19

ONLY GOD CAN GROW A TREE

HENRY FORD ONCE CALCULATED, AS PART OF HIS QUEST TO REDUCE the complexities of the production process to their simplest components, that it took 7,882 distinct tasks to make a Ford car, and he divided the number by the physical and mental capabilities of his workforce. “Strong, able-bodied and practically physically perfect men” were required for 949 jobs; 670 could be done by “legless men,” 2,637 by “one-legged men,” 2 by “armless men,” 715 by “one-armed men,” and 10 by “blind men.” The remainder required able-bodied workers, but of “ordinary physical and mental development.”

1

Yet the Amazon was a place where 7,882 organisms could be found on any given five square miles, the most diverse ecological system on the planet, one that did not move toward simplicity but stood at the height of complexity. One tree alone could serve as home to a dazzling variety of insects, along with an array of animals, orchids, epiphytes, and bromeliads. About 10 percent of the world’s five to ten million species are found in the Amazon, and there are, as one observer puts it, more “species of lichens, liverworts, mosses, and algae growing on the upper surface of a single leaf of an Amazonian palm than there are on the entire continent of Antarctica.” The region is home to 2,500 kinds of fish, about an equal number of birds, 50,000 plants, and an incalculable number of invertebrates. In 1913, it took one year to reduce the time needed to make a Model T from twelve hours and eight minutes to one hour and thirty-three minutes. Yet it is estimated that half of all the Amazon’s species remain undiscovered, and after centuries of observation scientists are still not exactly sure why the Amazon—unlike other forests, where leaves turn brown during the dry season—grows green and lush when the rain stops or how this reversed pattern of photosynthesis contributes to the broader seasonal distribution of water throughout the region. The slightest intervention could produce changes beyond the ability of Ford’s engineers to foresee, much less control: clearing the forest for rubber removed the leaf cover that sheltered the small creeks running to the river, with the added sunlight enriching the algae, which in turn increased the snail population. The snails were the vector for the small parasitic worm that causes schistosomiasis, a disease that affects human bladders and colons and didn’t exist anywhere in the Brazilian Amazon until it appeared in Fordlandia.

2

The clash between Ford’s industrial system and the Amazon’s ecological one, Chaplinesque in its absurdity when it took place over logistics, labor, and politics, grew even sharper when it came to the nominal reason for Fordlandia’s founding: to grow rubber.

EVEN AS ARCHIE Johnston struggled through 1931 and 1932 to comply with Dearborn’s social planning directives, he never lost sight of why he was sent to the Amazon, and at the end of his first year at Fordlandia he wrote to Charles Sorensen about how to move forward. “Everyone agrees that a great amount of work has been done at Boa Vista, and a great deal of money has been spent,” Johnston said, yet “very little has been done along the lines of what we came here to do, namely plant rubber.” He lamented that, having planted 3,251 acres after nearly four years of work, “we have merely scratched the surface. We have provided comforts for the sick, the staff, and the caboclo, but have done very little towards creating an early income for the Companhia Ford.”

3

Johnston shared the belief of his predecessors—Blakeley, Oxholm, Perini, and Rogge—that the sale of milled wood could potentially cover the plantation’s expenses until rubber was ready to be tapped. Not all of the trees logged could be used or sold. “We are aware that Mr. Ford dislikes very much to burn down timber,” he told Sorensen, “but it has to be done.” Felled trees either too soft or too hard piled up, “rotting in the skid-way.” Milled wood, unable to be shipped until the rainy season swelled the Tapajós enough to allow an oceangoing cargo ship to get to the plantation, warped in the humid climate, infested with termites. Once again caught between the ideals of Ford and the reality of the Amazon, Johnston pleaded for practicality: “We do not consider it wrong to burn this timber, simply because we cannot saw it. When we consider the whole question logically and seriously, it is just a question of whether we burn good American dollars (gasoline to get the timber) or burn the lumber.”

Johnston believed that if proper drying and storage facilities were built there were enough viable trees on the plantation to export three million board feet of milled, kilned hardwood a year. “We think the United States will be a splendid market,” he said. “We have lumber that will delight the eye of the American architects.” And to demonstrate, Johnston sent Ford and Sorensen that carved “little nigger boy” made out of Tapajós trees.

Johnston proposed a program of rapid expansion: he planned to run logging roads through 200,000 acres of the Ford concession, felling as many trees as the mill could cut and the market would bear. As the jungle gave way to machetes, broad axes, and cross saws, his men would burn the underbrush and prepare the ground to plant rubber. It would be only a few years, Johnston thought, before he had 100,000 acres planted with over 10,000,000 trees, producing 54,000 tons of rubber a year. That is, he hedged, “if all the trees were 100%.”

Sorensen responded quickly to Johnston’s letter, impressed with its determination and clarity. As to his planned “clearing of large areas and burning of same,” the head of the Rouge wrote, “you have outlined this in a manner that we all understand, and everybody here is in accord with your program.”

4

Success seemed in reach. After the initial troubles adapting Michigan sawing techniques to Amazonian wood, Mulrooney, Rogge, and Fordlandia’s other Upper Peninsula lumbermen had finally managed to get the sawmill and kiln to produce enough timber for the plantation’s basic needs. And though the mill would have to be refitted to produce lumber for export, Johnston was confident that all obstacles could be surmounted. “The lumber is there,” he told Sorensen, and “we know that the Ford organization can order any equipment and do anything within the power of man.” Though he did concede that “only God can grow a tree.”

5

But it was the Great Depression, and Dearborn was having trouble selling cars, much less exotic veneers. The company tried to find mills and furniture manufacturers in Michigan, North Carolina, and New England interested in Amazonian hardwood. Ford put out a glossy brochure highlighting the wide variety of wood and veneer available from Fordlandia’s mill. Sucupira, with its “unusual blend of colors,” resembled fumed oak. Massaranduba was an unusually strong wood, good for structural work on docks, railroads, and dance floors. Pau d’arco was attractively dark, while andiroba, a mahogany, would be perfect for radio cabinets and caskets. Spanish cedar lent itself to hand carving, as well as to cabinetry, and the mottled and striped muiracoatiara would nicely accent wall paneling where variation in color was desired.

6

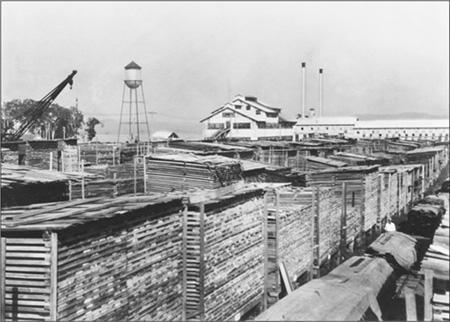

Fordlandia’s sawmill, with lumber stacked and waiting to be shipped

.

There were few takers, however. “The banking system is still very much of a muddled state” and the Rouge was running at reduced capacity, wrote the head of the Purchasing Department to explain why he hadn’t been fully devoted to finding a market for his wood. By 1933, Dearborn worked the numbers and concluded that, assuming it found a market and assuming that the mill could produce four million board feet of lumber a year, it would still lose $12,000 a month.

7

RUBBER WAS AN even bigger problem. From Fordlandia’s inception, it was assumed that the company that had perfected mass industrial production would grow plantation rubber. Observers of Ford noticed that he treated machines as “living things,” so in the Amazon it was to be expected that his men would treat living things—rubber trees—as machines. The model naturally was a Ford factory, either Highland Park or the Rouge, with its close-cropped rows of machinery, which cut down wasted movement, and its enormous windows and glass skylights, through which sun poured in, saving electricity by bathing the factory floor in cathedral-like radiance.

“You know,” Ford once said, “when you have lots of light, you can put the machines closer together.”

8

Johnston strove to apply the same kind of regimentation to the plantation that Ford did to the factory, spacing the trees close together and insisting that with the right discipline two men could plant between 160 and 200 trees in eight hours, at 2½ to 3 minutes per stump. But he soon admitted that he had trouble making the math work, as the pace of planting rubber was subject to more uncontrollable conditions—bad weather in particular—than was the tempo of an assembly line.

9