Forgotten Voices of the Somme (14 page)

Read Forgotten Voices of the Somme Online

Authors: Joshua Levine

Tags: #History, #Europe, #General, #Military, #World War I

A German trench hit by artillery fire.

was just like a veil of sequins that were flashing and flashing and flashing. And each sequin was a gun.

The artillery had orders – we were told – not to fire when an aeroplane was in their sights. They cut it pretty fine. Because one used to fly along the front on those patrols, and your aeroplane was flung up by a shell which had just gone underneath and missed you by two or three feet. Or flung down by a shell that had gone over the top. And this was continuous, so the machine was continually bucketing and jumping as if it was in a gale. But in fact it was shells. You didn't see them: they were going much too fast. But this was really terrifying.

Corporal George Ashurst

1st Battalion, Lancashire Fusiliers

It'll never be seen or felt again. I walked along our front line, looking at the German lines, and I could see the bursts of the shells, all over, big ones in the distance. We could see the dirt from the sandbags, dancing up and down, and when you turned around, you would see flashes all along our skyline. Hundreds of them. You couldn't see the guns – just the flashes. And the noise was like a hundred trains over the top of your head, all at once. I thought the bombardment would be a success. I thought it would shift Jerry. He couldn't stand up to something like this! Well, he didn't have to! He had dugouts thirty feet deep!

Stephen K. Westmann

German Army Medical Corps

For seven days and nights we were under incessant bombardment. Day and night. The shells, heavy and light ones, came upon us. Our dugouts crumbled. They fell upon us and we had to dig ourselves and our comrades out. Sometimes we found them suffocated, sometimes smashed to pulp. Soldiers in the bunkers became hysterical. They wanted to run out, and fights developed to keep them in the comparative safety of our deep bunkers. Even the rats became hysterical. They came into our flimsy shelters to seek refuge from this terrific artillery fire.

Looking towards

Thiepval

in the early morning.

18th Battalion, Manchester Regiment

We were told by our officer that we were to take part in the attack, and the men were excited. Everybody thought it would be a walkover. The bombardment was so heavy, and the men were in excellent spirits. They were all volunteers, and they were looking to beating the Germans, and finishing the war quickly. No one believed there could be a defeat. Everyone was eager, and anxious to go forward.

11th Battalion, Suffolk Regiment

A couple of days before the attack, we were waiting to go up. We were in a field, with a hedge between us and the next people, and all of a sudden a rifle shot went off. We didn't take much notice. We thought someone was cleaning his rifle, and let one off, but then somebody said, 'Someone's shot himself in the knee!' We didn't trouble to go through and look, but a few minutes later, through the gate, came this chap being carried on a stretcher, with two men marching each side of him with bayonets fixed. It confirmed that he'd shot himself through the knee. I've often wondered what happened to him.

Corporal George Ashurst

1st Battalion, Lancashire Fusiliers

We were issued with the new

steel helmets

before the battle. I didn't like them. They were damned heavy and uncomfortable things to put on your head. They only just fitted and fellows thought they'd very soon rub them bald. I thought the same. I wore it. I had to. But you got quite used to them in a short time.

Lieutenant Norman Dillon

14th Battalion, Northumberland Fusiliers

I was standing in a reserve trench, when a man came up to me with a peculiarlooking helmet. It turned out to be one of the new steel ones. 'What's that?' I asked, and I put it on – as one does with a new hat. At that very moment, a shell burst overhead and knocked the helmet off, putting a great dent in it, but leaving me unharmed. I was very grateful for that helmet – even if it was a very uncomfortable thing to wear and, at first, a very strange thing to look at.

They looked like straw boaters made in steel, and they were very uncomfortable because they didn't sit on your brow like a straw hat does; they pressed your hair down on your scalp and made you want to scratch the whole time. There were plenty of reasons to scratch in the trenches, without having to add to them.

21st Battalion, Northumberland Fusiliers

During the build-up to July 1, a carrying party was caught in shellfire whilst carrying poison

gas

. One of the gas cylinders was fractured, and before they could do anything, seventeen of these men were gassed, and eventually died. My battalion had to go out into

Albert cemetery

, and dig the graves for these men. It was a very heavy job, because it was chalk subsoil, and when you've got three foot of soil off, the rest is solid chalk. But we got the graves down to the depth required, and then the bodies were brought, and the priest did his work and we laid the bodies down. And I looked across and I saw one of my men, sitting crying. I went across. 'What's the matter?' He said, 'I can't do it, with his face there, looking up at me!' So I said, 'Turn around. I'll cover his face up, and you can get on with the job.' 'Thank you very much,' he said, 'from the bottom of my heart.'

Corporal Harry Fellows

12th Battalion, Northumberland Fusiliers

One night, just before July 1, there was supposed to be a raid, and we were all standing to, in the trench, but nothing happened. At stand down, at daylight, the lance corporal who was in charge said he wanted to go to the latrines, so off he went. I was looking though a periscope, over the top, when I heard somebody behind me and I thought the corporal had come back. I turned round – and I saw a German. He had a white bib on his front and back, and a Maltese cross in luminous paint. He had two stick bombs on each side of his belt, a dagger and a revolver, and the only thing he said was, 'Cigarette!' I gave him a cigarette, and I never thought of disarming him. He took the bombs out of his belt, put them on the fire-step, sat down and I sat beside him, and both of us sat there smoking. Some of the other chaps came into the trench, and said, 'Who's this?' He couldn't speak English, we couldn't speak German, and all we understood was that he pointed to himself and said, '

La

guerre kaput

!' meaning the war was finished for him. He showed us a photo of his wife and two kiddies. He gave me his revolver, he gave two of the other lads a bomb each and another lad got his revolver. Shortly afterwards the sergeant-major ran up with his revolver; the word had gone round that a German had captured us, and we were being held hostage in the trench! Then our captain arrived, and he took the German away, and we had to hand over our souvenirs.

Afterwards, our battalion intelligence officer told me that this German had joined a specially trained unit for raiding trenches. They used to lay tapes out across no-man's-land before they made a raid, but on this occasion the tape had been moved, and his raiding party had come to the wrong part of the wire. He'd found a zigzag in our wire, he'd got into the trench and he'd stood at the end of a communication trench for an hour, waiting for daylight, and he never saw a soul. And then he came up behind me. He'd said that the Germans knew there was going to be an attack on June 30.

Private Albert Day

1/4th Battalion, Gloucestershire Regiment

We knew something terrible was going to happen; the Germans knew it as well. My two cousins sorted me out. We were out of the line, and we had an hour or two together. One cousin was a tough young chap, a strong, healthy kid, but his brother Fred was a bit more weak. We spent most of the evening together, and had a few drinks. When they were leaving to go back to their battalions, Fred shook my hand and said, 'You will never see me again, Bert.' 'You mustn't talk like that, Fred,' I said. 'I feel it!' he said.

Corporal George Ashurst

1st Battalion, Lancashire Fusiliers

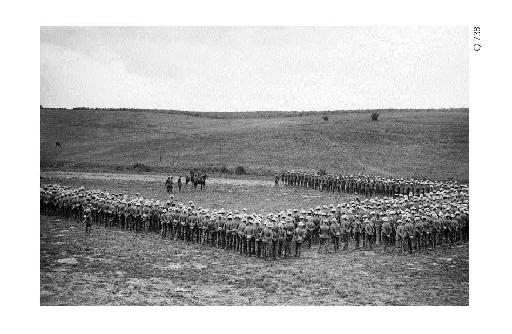

Our battalion was formed into a three-sided square outside our village – and up came the general. He was on horseback, with one or two lagging behind him, and he started to make a speech; he said that we were going to make this attack. And he knew that we would do our duty, as we always had done before. He said that there'd be no Germans left to combat us when we got over there. The barrage and the shelling would be so terrific, the guns would blaze day and night for a whole week. He said that if you placed all the guns side by side, wheel to wheel, they'd stretch from the English Channel to the

The 1st Battalion, Lancashire Fusiliers being addressed by

General de Lisle

on June 29. One of these men is

Corporal George

Ashurst.

Alps. He made it sound like it was going to be a walkover. You can imagine what all the lads were saying round about. They were cursing during the speech: 'Shut up, yer bastard!' Our officer would turn round and whisper, 'Shut up!' But it didn't make no difference. The men all kept swearing and cursing: 'I wish the bloody horse would kick him to death!'

Private Donald Cameron

12th Battalion, York and Lancaster Regiment

On June 30, the Corps Commander,

General Hunter-Weston

, made a speech, saying we were superior to the Germans in arms, artillery and everything else. He said that by the time our artillery had finished bombarding their trench and we went over, we'd be more or less on a picnic. What a lot of bullshit he talked. After that, the regimental band played, 'When You Come to an End of a Perfect Day'. As

Larry Grayson

says, 'What a gay day!'

9th Battalion, York and Lancaster Regiment

On the last day of June, we marched up. We knew that a lot of us would be casualties on the morrow, and it was interesting to see the different response from different soldiers. I remember one man who walked off on his own, communicating with himself. He seemed moody and I tried to cheer him up. Others tried to put on a form of jollification. When the march started towards the line, it was all happy: singing 'A Long Way to Tipperary', biscuit tins being hammered, all to keep up the spirits.

Lieutenant Norman Dillon

14th Battalion, Northumberland Fusiliers (attached to 178th Tunnelling Company Royal Engineers)

The mines were blown on the morning of July 1, and I was within half a mile when they went up. It was tremendous. The craters were eighty yards across. I believe the shock was heard in London.

Lieutenant Cecil Lewis

3 Squadron, Royal Flying Corps

When the zero hour was to come, we were flying over

La Boisselle salient

, and suddenly the whole earth heaved, and up from the ground came what looked

like two enormous cypress trees. It was the silhouettes of great, dark coneshaped lifts of earth, up to three, four, five thousand feet. And we watched this, and then a moment later we struck the repercussion wave of the blast and it flung us right the way backwards, over on one side.

Corporal Don Murray

8th Battalion, King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry

New drafts had come out from England, young boys who'd never been in action, and they made us up to our full strength. And we were all in dugouts, ready to go over.

Major Alfred Irwin

8th Battalion, East Surrey Regiment

I was young and optimistic. I didn't think much about the future. I took it for granted that the wire would be cut, and that we would massacre the Boche in their front line.