Forgotten Voices of the Somme (13 page)

Read Forgotten Voices of the Somme Online

Authors: Joshua Levine

Tags: #History, #Europe, #General, #Military, #World War I

When I was on relief duty, the Germans blew a small mine, which killed an officer and two men. That was one of the accepted risks. It was all right in the mine shafts. There was a primitive form of ventilation from the surface – a man blowing a bellows down a long pipe leading under the chalk. There was

very little support needed, so we didn't need lots of props holding the roof up. The tunnels were about three feet high by two feet wide.

The unit was commanded by a relation of the Duke of Wellington, a very nice chap called

Wellesley

, who was killed in a stupid way while souvenir hunting, when he tried to pull a rifle grenade to pieces and it blew up in his face. The men of the company were miners. They did the digging. No troops came in to help. The earth had to be carried out in sandbags, because any noise of a truck trundling would give away the situation at once. They brought out all the spoil themselves. Morale was very high amongst the tunnelling company, strangely enough. One of the strangest things was that we were supplied with very nice little 21/4 horsepower twin-engined

Douglas motorbikes

. Why they were supplied to a tunnelling company, I have not the least idea. I can only assume that the authorities considered the tunnelling companies certain death to belong to, so their morale might improve if they had a motorbike with which to get out of the line and have a drink. I certainly considered it pretty risky. You were bound to feel that death was around the corner.

Sergeant Charles Quinnell

9th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers

The miners were a rough lot but, by God, they were brave men. They used to mooch into the trench. They had a rifle but they didn't know how to fire it; they weren't supposed to, they were just miners, you see. You could always tell a miner, he never bothered to clean his buttons. He was a miner, he wasn't none of these posh soldiers. We had a sergeant who was a very regimental type of man. His first day in the trenches, two of these miners slummocked along into the front line, walking along with their heads down. They took no notice of us, and we took no notice of them. Anyway, this sergeant didn't know who they were and he yelled out, 'Halt!' – and they didn't attempt to halt, and he gave the order 'Halt!' again – they didn't, so he brought up his rifle – bang, he shot the first man through the head and the bullet went through both of their heads. He killed them stone dead.

Corporal Don Murray

8th Battalion, King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry

Before the battle there was a constant procession of guns, guns, guns going up.

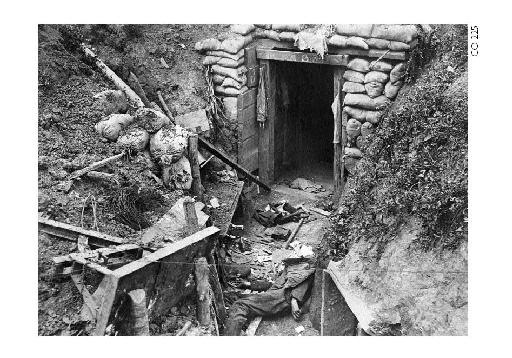

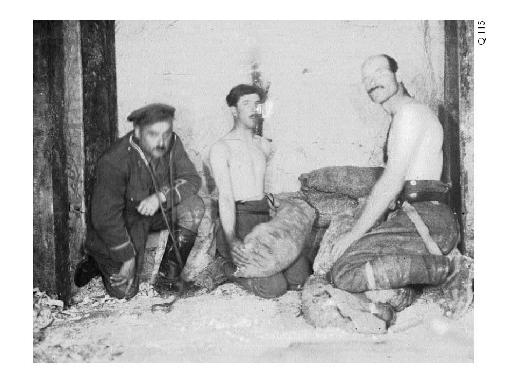

Miners laying a charge in a mine chamber.

The big guns used to lie miles back, but they were bringing them right up into the front. Right up.

Second Lieutenant Stewart Cleeve

36th Siege Battery, Royal Garrison

Artillery

We were the first battery to arrive with guns any bigger than 6-inch, and caused a great deal of attention by the higher authorities because of the sheer weight of ammunition which these

8-inch

howitzers could produce. But they were improvised howitzers, because they were old

6-inch Mark Is

, cut in half and the front half was thrown away. They were monstrous things, and extremely heavy, but the machinery of the guns was very simple and that's why they did so extremely well, and they didn't give nearly as much trouble as some of the more complicated guns that came to appear later on.

We moved to a splendid position near

Beaumetz

. The guns were dug into an enormously deep bank about ten feet deep by the side of a field. The digging we had to get into that gun position was simply gigantic. We camouflaged it extremely well by putting wire netting over it, threaded with real grass. We had an awful job to manoeuvre the guns into it. We had to manhandle these enormous monsters – they weighed several tons. When they were in position, they were very well concealed – so much so that a French farmer with his cow walked straight into the net, and both fell in. We had the most appalling job getting this beastly cow out of the gun position. The man came out all right ... but the cow ... However, it was enormous fun. It was one of those delightful moments when you all burst out laughing.

Signaller Leonard Ounsworth

124th Heavy Battery, Royal Garrison Artillery

For our four

60-pounder

guns, we accumulated 5,000 rounds of ammunition in holes and pits. We dug some pits, but we'd strewn them out within a radius of a hundred yards behind the battery, so as not to risk too much being hit, in case the enemy started shelling round there. And by the end of the week of bombardment, we'd used up all that ammunition – plus what had been brought up, as well.

It was brought up in wagons to the nearest point on the road, and then we had to carry it from there by hand after dark, to whatever pits we were putting it into. We carried it by slinging two shells together with a stick, and slinging

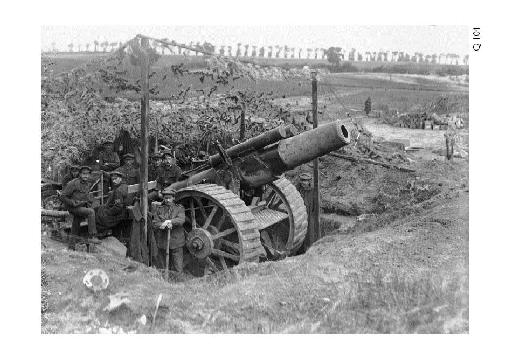

An 8-inch Mark V howitzer in a

camouflaged

emplacement.

them over the shoulder. They were very hard on your shoulder, a 60-pounder shell, so we used to put a folded sandbag under our braces, like a shoulder pad, otherwise your shoulder was very sore by the end of the spell.

Bombardier Harold Lewis

240th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery

On the

18-pounder

gun, the officer was Number One and he would shout at the rest of us. The best gun layer, the Number Three, was an NCO. He opened the sights. Number Two was the range drum. Numbers Four and Five were the loaders. Five had to work the 'corrector bar', a brass affair like a slide rule. I was Number Four, and I had to be pretty active, because if we were keeping up a rate of fire, I would have to dispose of the hot charge case as it came out. If the cases were just thrown on the ground, people would fall over them. I would have the next round ready as the breech opened, catch the brass charge case as it came out, throw it aside and load. We could achieve twenty rounds in a minute, but not continuously all day long. The gun had to be laid for each individual round, because the recoil could interfere with the accuracy.

Corporal Don Murray

8th Battalion, King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry

We were working like beavers. We were carrying trench mortars that weighed fifty-six pounds each, one on each end of a sandbag, slung over our shoulders, taking them up the communication trench into the front line. Stacks and stacks of them.

1/11th West Riding Howitzer Battery, Royal Field Artillery

Most of our ammunition was

shrapnel

shells. A shrapnel shell was a shell with a small charge at the bottom and the body of the shell was filled with small balls; dozens of little pellets. The fuse on a shrapnel shell could be set to explode a given number of seconds after it left the gun. The case of the shell itself got very much thinner towards the top – so when the explosive charge at the bottom went off, it threw all the pellets forward, rather like the shot out of a shotgun. The idea was to set the fuse so that the whole thing exploded short of the advancing infantry. So that all these pellets would spread out and cause death and destruction.

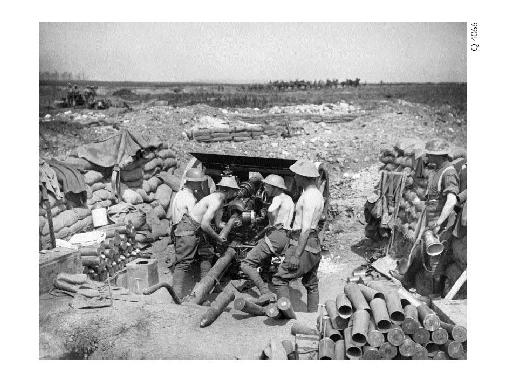

An 18-pounder gun team in action.

Captain Philip Neame VC

Headquarters, 168th Infantry Brigade

All the German trenches were defended with a thick belt of barbed wire in front of them, and in the early attacks in the war this barbed wire had to be cut either by hand or by what were known as

Bangalore torpedoes

[twentyfoot long steel pipes filled with explosives, placed in position by hand]. Well, then it was discovered that shrapnel shells – set to burst very low – would blow lanes through this barbed wire. So artillery fire became the recognised way of cutting the wire. They would cut a series of lanes through the barbed wire through which the infantry could get.

6 Squadron, Royal Naval Air Service

We were ordered through to take up a spotting position for a whole week before the battle started. We lay in a little valley there – a slight proclivity in the chalk, and observed quite successfully for some time. On the eve of the battle, the night before they were to go over at dawn the next morning, the combined armaments were crashing all together. The whole earth trembled.

The line that was holding down the balloon was shaking. You could feel the vibrations coming up through the earth, through your limbs, through your body. You were all of a tremor, just by artillery fire only. Not so much from the crashing of the shells, as the gunfire from the rear, all concentrating in one wild blast of gunfire. It was shattering. The whole ground trembled, and you felt sorry for anyone within half a mile of wherever they were piling it. It must have been terrible for them.

3 Squadron, Royal Flying Corps

Flying through the bombardment was terrifying. We were flying down to about one thousand feet. And when you went right over the lines, you were midway between our guns firing and where their shells were falling, and during that period the intensity of the bombardment was such that it was really like a sort of great, broad swathe of dirty-looking cotton wool laid over the ground. So close were the shell bursts, and so continuous, that it wasn't just a puff here and a puff there, it was a continuous band. And when you looked at the other side, particularly when the light was failing, the whole of the ground

British artillery bombarding German trenches at

Beaumont Hamel

.