Forgotten Voices of the Somme (8 page)

Read Forgotten Voices of the Somme Online

Authors: Joshua Levine

Tags: #History, #Europe, #General, #Military, #World War I

Well now, you always left a little of your tea in the bottom of your mess tin, and you would dip a corner of your towel in the tea and wipe round your face, and that was your morning ablution. Then there'd be a little tiny drop of tea still left – and you put your

shaving

brush in that and you would lather your face and you would have your shave. We had to shave in the front line, otherwise – especially the dark chaps – we'd look like brigands.

Sergeant Frederick Goodman

1st London Field Ambulance, Royal Army Medical Corps

We had always used cut-throat razors, but it was just about this time that Gillette brought out the first safety razor. And on the Somme, we'd only have to put our safety razor down for a moment or two, and when we came back to pick it up, it would be gone.

Corporal Jim Crow

110th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery

You got a wash when you could. Six of us would wash and shave in a pint pot. We had to keep shaving.

Private Reginald Glenn

12th Battalion, York and Lancaster Regiment

For a proper wash, you had to wait until you got back out of the line. We used to use a sugar factory's vats for bathing. There'd be twenty of us in these vats, twenty feet in radius. We had soap and towels, and they filled them with lukewarm water.

12th Battalion, Royal West Surrey Regiment

All the water used in the trenches was chlorinated – and it tasted of chlorine. It was carried from one place to another in old petrol tins, and you could still taste the petrol. With the combination of petrol and chlorine, it wasn't all that pleasant. We had strict orders to boil water before it was used.

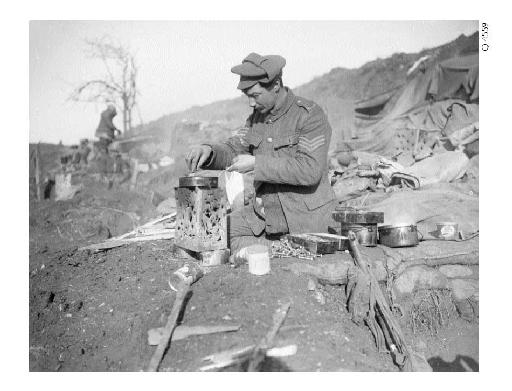

A sergeant cooking his dinner.

Sergeant Charles Quinnell

9th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers

After breakfast, there would be inspection of the trench and also rifle inspection. Although you were in the line, you had to keep your rifles spotlessly clean and always ready for use. The inspection of the trench became necessary because the

rats

and the fleas in summer were really a nuisance. For instance, if you threw your empty bully beef tin over the top, that would attract the attention of the rats so in every bay would be a sandbag pegged on to the wall and in there would be the empty wrappings and empty bully beef tins and such stuff as that. Now these sandbags were collected every night. Every company had a sanitary man and it was his job to come along and take them to a shell-hole, tip the lot out and then cover that with earth. And his job was also to empty the buckets, which were biscuit tins, from the

latrines

. Everybody hated this job and it was given to some men as punishment. Actually, one or two men preferred it, because they could do the job in about an hour, and that was their only duty for the whole twenty-four hours.

Private Reginald Glenn

12th Battalion, York and Lancaster Regiment

There were certain sections put out for latrines. The latrine was a hole in the ground with a piece of board across. You squatted on the board, but there was no paper. You used the earth and the sand. There was a 'sanitary squad' who used to come along and bury the stuff. Very often, the Germans could trace where our latrines were, by seeing people going backwards and forwards, so they got them well taped with

minenwerfers

. You'd be sitting there, and you'd see one of these come over, and you'd run with your trousers down.

Second Lieutenant W. J. Brockman

15th Battalion, Lancashire Fusiliers

The smells in those trenches were terrible. It's stayed with me all my life. Excreta, urine, cordite from exploding shells.

7th Battalion, Dorsetshire Regiment

There were always rats in the trenches. I wouldn't say as big as cats – but as big as kittens. They were enormous. I've never seen any rats in England like

them. They used to feed on anything we threw away, or garbage, or on dead bodies. There were plenty of bodies about. We used to put a pole across the trench, and the rats were very tame, they would run across that pole, and we would punch them off with our fists. Kill them. That was one of our pastimes.

Rifleman Robert Renwick

16th Battalion, King's Royal Rifle Corps

The rats were worst in the trenches we took over from the French. The French were a little bit careless in leaving food lying about. The rats were terrific. We spent most of the daytime putting a bit of cheese on the end of our bayonets. They would come to the end of the bayonet, and then we'd shoot them. We couldn't miss them from there. They were very annoying. Filthy. They'd get at the rations. In one part of the line, we were sleeping in wire beds in dugouts, and the rats were seizing our haversacks with the food in, so we hung the haversacks underneath the bed, and the rats were still trying to get at them.

Private Victor Fagence

12th Battalion, Royal West Surrey Regiment

After being in the trenches for a very short time, every individual became verminous.

Lice

. Body lice. Getting rid of them took part of our time. Usually, when one got back behind the line, in a comparatively quiet place, one would take off one's shirt, and crack the lice between our thumbnails.

Sergeant Charles Quinnell

9th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers

The favourite way of getting rid of the lice – or trying to – was to take your trousers off, turn them inside out and run the seams of your trousers over a lighted candle, and you could hear the eggs going, pop, pop, pop... You'd put your trousers on but next day you had just as many lice. There were various powders sent out from England, from relations and so forth, and also there was a lice belt. That was a piece of thick angora wool which you tied round your waist and it was impregnated with something, but the only thing it did was to give a demarcation to the lice. Those above didn't mix with those below the belt.

Private Thomas McIndoe

12th Battalion, Middlesex Regiment

I had a very sensitive skin, and my sister used to send me Keating's powder to deal with the lice. But that was no good at all. Then one day, a member of the

Pioneer

Squad came into this latrine. He had been disinfecting the trench with a cylinder of white disinfectant powder. I was young and inexperienced, and didn't know what this powder was, but I asked him if he'd oblige me by giving me a little. But I didn't tell him what purpose I wanted it for. And he gave me a little in an envelope that I gave him. And after he'd left I emptied the contents of this envelope down the inside of the seam where the lice had gathered. But I soon realised that the powder I'd used had a destructive nature to it, and was burning the cotton of the seam of my trousers. And eventually it rotted the seam and the trousers fell apart. I subsequently found out that it was chloride of lime.

I went along to the medical officer because this stuff had burnt the inside of my legs and my legs were very raw. When I sweated, it had set the powder into a burning mass which was burning my legs and also the clothing. The medical officer gruffly said, 'What's your trouble?' so I said to him, 'I'm lousy, sir.' He said, 'Lousy? Hm . . . we're all lousy.' I said, 'Well, I've never been used to it, sir.' He said, 'Do you think I have?' I'll never forget that. And he said, 'What have you been doing?' So I told him, I briefly outlined what I'd done. And he said I'd rendered myself unfit for duty. But in no way I was going to be excused duty. So I had to just carry on as usual.

Sergeant Charles Quinnell

9th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers

For the midday meal, two or three chaps could amalgamate and one would open his tin of Fray Bentos bully beef [corned beef]. On top of the bully, there was always a quarter of an inch of fat. Now that fat was very precious because with it, you could chop up the bully beef, and fry it up in your mess tin lid. And you could smash up your biscuit with your bayonet, powder it, and put it in with the chopped bully. That was quite tasty.

Sometimes we were issued with raw potatoes. Now raw potatoes in the front line – to the uninitiated – were simply a waste of time, but when the chaps had been out there a few months they utilised everything they could lay their hands on. You could take a raw potato and if you cut it into

very, very thin slices then you could fry that in your bacon fat in the morning. It was like sauté potatoes, and it was quite edible.

124th Heavy Battery

, Royal Garrison Artillery

We used to have Maconochies – a sixteen-ounce tin, which was supposed to have ten ounces of meat and four ounces of potato and two ounces of other vegetables in it. And it was a flat tin, you could heat it up on a fire – puncture a hole in it, you see, otherwise it would burst.

Private Harold Hayward

12th Battalion, Gloucestershire Regiment

We carried emergency rations that were not to be eaten until we were given instruction to eat them. The best thing I can tell you is that they were made up of hard dog biscuits. It had to be a good dog to bite them. When we were in action, and there was no orderly ration, I had recourse to these biscuits. I saw several fellows with broken teeth trying to bite them. I used to try and break them with my knife, and then just suck them down. Hardly any taste at all. But there must have been some nutrient in them.

Rifleman Robert Renwick

16th Battalion, King's Royal Rifle Corps

We used to go on ration parties when we were out of the line, on rest. It was almost worse than being in the trenches. You could be out in the open, sometimes under heavy fire. You'd carry the food in sandbags, and the water in unused petrol tins. You'd collect it from a dump, and you'd go up through the communication trenches. You'd take it up to the front line, and give it to the sergeant, or the officer, and they'd distribute it.

14th Battalion, Northumberland Fusiliers

There were constant

carrying parties

. We were carrying forward rolls of barbed wire, pickets for hanging it on, shovels, sandbags, wood, posts and wire for revetments and the sides of trenches, duckboards for wet places. Everything had to be carried up.

Sergeant Charles Quinnell

9th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers

During the day, in the front line, there was always some

digging

to be done. You see, the sides of the trenches were always giving way especially in wet weather, and you would find that perhaps during the night the side of the trench had come in. Well, the trench had to be built up with sandbags filled with earth. There was always a repair job to be done; there was always a support trench needed repair.

And there was always a lot of sleep going on during the daytime. You see, you reversed the order of your usual living.

Night-time

was the period of activity. There was always something to do at night-time. There was the ration party, there was the water party, there was a

wiring

party, there were patrols. After a few weeks, a soldier could curl up, and he could be asleep in two minutes. If nobody came for you to do a job you simply got down to it and you were asleep, any time of the day.

At night-time, if there was any suspicion of activity,

Very lights

would go up. Each platoon sergeant had a Very light pistol and he also had his cartridges, and if the sentry reported any activity in front, the sergeant would send a Very light up. This pistol was like a brass starting pistol, and you'd cant it at what angle you think you want the light to drop, and plop! And that would go up in the air and light everything up.

Second Lieutenant W. J. Brockman

15th Battalion, Lancashire Fusiliers

If you were in

no-man's-land

when a Very light went up, your instinct was to lie down – but that was wrong. You should stand absolutely still. There were all sorts of things you could be mistaken for in no-man's-land – wire and stumps of trees.

Sergeant Charles Quinnell

9th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers

Wiring was always done in the dark and it was done by a party who had been trained. It sounds peculiar I know but there was a certain amount of waltzing to it. Barbed wire used to come on a wooden framework with a hole through the centre, and a pole used to be put through that framework, one man on either side. The man who did the actual wiring was always issued with a pair of very thick leather gloves because barbed wire can be very, very vicious.