Forgotten Voices of the Somme (7 page)

Read Forgotten Voices of the Somme Online

Authors: Joshua Levine

Tags: #History, #Europe, #General, #Military, #World War I

Private Basil Farrer

3rd Battalion, Green Howards

In one trench, there was an arm protruding, which we used to shake every time we went by, going, 'Cheerio chum.' I have been in trenches where you thought, 'Hello, there's a body here.' The ground would be soft and smelly, and there would be a nasty sweet smell. You became acclimatised to it.

Private Thomas McIndoe

12th Battalion, Middlesex Regiment

One particular morning, I was in the corner of a traverse, and I thought, 'Hello! I just heard a high-calibre shell being discharged!' There had been one or two over beforehand, and this one was coming a bit close. And I thought, 'Good heavens, yes it is, it's on its way!' Instinctively I got down under the parapet. Sometimes you wish the earth would shrink, so as to let you get in, you know. The shell landed – but no bang. And it covered me with dirt. I wouldn't be here if it had gone off. It was a calibre 4.7 shell which is round about the size of a jug.

In my excitement, I scooped it up in my hands, and brought it down to the

An

unexploded

German shell. Not to be moved ...

fire-step. It was still warm, see, and I thought, 'Oh yes, it's a cracker. I'm glad you didn't go off, old man!' Some ten minutes afterwards my platoon officer came round. He was a nice chap and he said, 'What have you got there, mate?' I said, 'Well, I'll tell you what I've got here, sir. It's one that dropped right on the parapet where I was standing.' He said, 'Yes?' I said, 'It buried itself in that sandbag there.'

So the officer got on the phone to an artillery officer from a battery, who came up later that morning. I explained it to him. And he said, 'And when did you take it from the sandbag?' I said, 'Oh, when it landed.' And he called me a bloody fool. And he said, 'The mere fact of you touching it and disturbing it, it could have gone up. You're lucky! You're very lucky!' I said, 'I know. I realise I'm lucky. It should have gone up when it landed.' So he said, 'I want you to put it back exactly where it was.' So I did. And before I had done it, he said, 'If I had seen that

when

it landed, we could have located that battery within twenty yards.' So I expressed my regret and promised to be more careful in the future.

Corporal Harry Fellows

12th Battalion, Northumberland Fusiliers

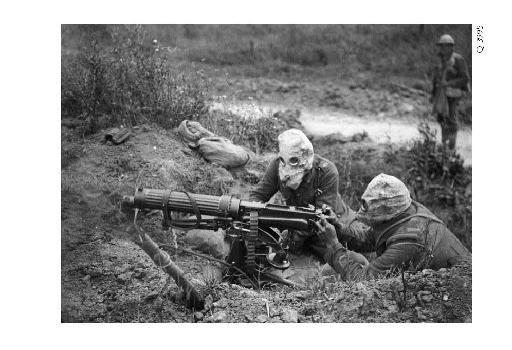

Artillery fire was spasmodic – but machine-gun fire was deadly. With a machine gun, men could be mown down, like mowing a field of standing corn.

17th Battalion, King's Liverpool Regiment

The

Vickers

machine gun was water cooled, and the water was contained in a jacket. Providing you had been continuously firing, you could take the tube away that led from the jacket and you had enough boiling water to make a cup of tea. Or a pot.

Private Tom Bracey

9th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers

They couldn't get anyone to go on the machine gun. People thought the machine-gunners only lived a month. We were respected by the rest of the company, though.

Sergeant Ernest Bryan

17th Battalion, King's Liverpool Regiment

The Lewis gun was an air-cooled machine gun. This had advantages and disadvantages. The advantage was that you could cover ground that couldn't be covered by the Vickers machine gun. You could sling it on your arm, and drop it down in another portion of the trench, just like a rifle. And it had terrific firepower – it could fire at between seven and eight hundred rounds a minute. Of course, that doesn't mean you could get that off – because there were only forty-eight rounds in a magazine, and unless you had a tremendous target, you wouldn't fire a full magazine.

Corporal Harry Fellows

12th Battalion, Northumberland Fusiliers

There were only forty-eight rounds in each Lewis gun magazine. It was a very delicate gun. You only had to have the slightest bit of dirt in it, and you had a stoppage. In our training, we were shown a drill to run through, 'Number One Stoppage, Number Two Stoppage, Number Three Stoppage' and so on. I went on a course with about forty other NCOs, and the instructors were members of the

Honourable Artillery Company

. They were going through this drill, when suddenly an NCO jumped up, and he said, 'I want to ask my friends a question. When the Germans are coming at you, and your gun has seized up, have you ever gone through this drill?' Not one NCO said they had. The gun had a little wooden handle, called a cocking handle, and when the gun stopped, you put this handle in, and you pulled it back to reload the gun. You fired again, and if it didn't fire this time, you dumped the bloody gun. That was all there was to it. When the Germans were attacking you, and you were looking into their eyeballs, how could you start doing a drill? It was the last thing you were thinking of.

Private Ralph Miller

1/8th Battalion, Royal Warwickshire Regiment

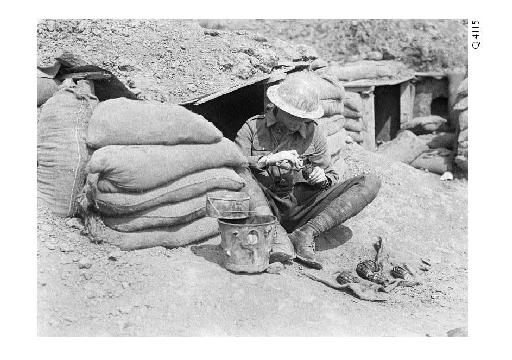

The finest hand grenade of the war was the Mills bomb. It had a pin to pull out, and then you held the lever down, and when you loosed it, it flew up, shook the detonator, and the bomb exploded about three or four seconds after you threw it.

A Lewis gun in action in a front-line trench.

British machine-gunners wearing gas helmets.

Second Lieutenant Tom Adlam VC

7th Battalion, Bedfordshire Regiment

Certain people were frightened of

Mills bombs

. I was teaching one fellow, and he was absolutely shaking. I knew he was a good chap. But he was so afraid, you see. 'Take the pin out of the bomb,' I said, which he did, 'and while you've got it in your hand, don't let the spring go off and you're all right.' Then I said, 'Now, now, hold yourself. Nothing can happen while you've got hold of it like that. Now, just put your arm back and throw it over there.' But he hung onto it until the last minute, and he brought his arm down and let go. And it lodged in the parapet he was supposed to be throwing it over. I shouted, 'Run, you silly . . . !' We both ran back and got behind the traverse. And it blew the parapet down. He was a grand chap really – just frightened of bombs.

Private Basil Farrer

3rd Battalion, Green Howards

I was in a bay, once, and a Royal Engineer came along the trench, and he had got one of these bombs in his hand. He was playing with it – and he was drunk. I shouted to him, 'Hey! Be careful, chum!' He went around the next traverse, and 'BANG!' I looked around, and it stank of rum. He was dead, in absolute pieces.

Sergeant Ernest Bryan

17th Battalion, King's Liverpool Regiment

The Mills bomb could be thrown twenty-five yards – quite accurately – by the average man. If you were throwing it a short distance, you had to be very careful, because the enemy could pick it up and chuck it back at you.

11th Battalion, Border Regiment

The part of the line I was on was just fifteen yards from the German line. We were so near that every morning, a German used to shout to me, 'Hello, Tommy!' and I would reply, 'Good morning, Fritz!'

Corporal Jim Crow

110th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery

One of our infantrymen was on the German barbed wire, badly wounded. We could see him moving every now and again. In the end,

Major Anderton

A soldier cleaning Mills bombs. These were hand grenades, serrated like a pineapple on the outside, which exploded to form shrapnel.

pulled his revolver out, climbed over the parapet, walked straight to this man, picked him up and carried him back. He walked as though he was on parade. The Germans never fired a shot at him as he went, they never fired a shot as he went back, and they cheered him as he lifted the man on to his shoulders.

16th Battalion, West Yorkshire Regiment

There was something very strange about our sector. Every time the battalion was changed, the Germans knew who was coming in. How they found out, I don't know. But this footballer,

Dickie Bond

, a right-winger who played for

Bradford City

, came into the front-line trenches. And the Germans called out to us, 'We know Dickie Bond's in the front line!' Not long after that, he became a prisoner of war. And we heard later that he was playing football for the German army.

Sergeant Charles Quinnell

9th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers

Every morning in the front line, everybody 'stood to' – from half an hour before dawn, until half an hour afterwards. The sentries would be looking through periscopes, and everybody was prepared in case there was an attack – because the favourite times for attack were dawn or dusk. That was because, at dawn and dusk, nobody could get a sight on you with a rifle. After 'stand to', if nothing untoward had happened, the order came to 'stand down'. And then instead of a sentry to every bay, there would be perhaps two or three sentry groups in the whole company's front, and the rest of the men would see about having their breakfast.

Each man prepared his own breakfast. You'd go along to the sergeant, and your mess tin would be three parts filled with water. You put that on the hob and then you would light your chips of firewood under it, and boil your water. When the water was boiling, you'd put your tea and sugar in that, and you'd go along to the man who had the milk. You'd never open a tin of milk or a tin of jam fully because the rats would get to it: you'd simply punch a hole on either side of the lid, and blow on that one and it would squirt out the other. Primitive Methodists we were!

Now you've got the glowing embers of your fire and with your mess tin lid which had a folding handle, you'd open that, you'd put your rasher of bacon in

there and put a few more sticks on your fire, and you would fry your bacon, and in the fat you would put a slice of bread, or perhaps a piece of biscuit to soak up the fat – and there you are with a breakfast.