Framingham Legends & Lore (16 page)

Read Framingham Legends & Lore Online

Authors: James L. Parr

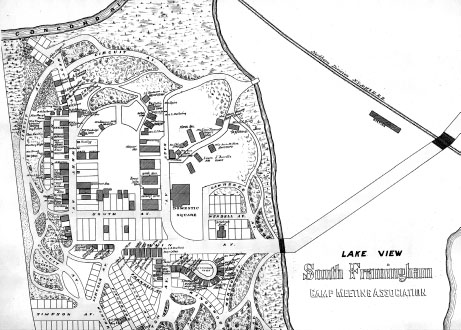

Map of the Chautauqua grounds at Lakeview, 1895.

Beginning in mid-July, trains would arrive at the Lakeview station at the foot of Mount Wayte, depositing hundreds of families and individuals from across the country. Carriages would then transport the attendees to the campground for their Chautauqua experience. The sounding of the Chautauqua bells at the top of the hill would signal the start and the end of each day's activities. While the main focus of the meetings was religious in nature, many cultural and educational lessons were offered during the ten-day sessions. Each week featured special theme days, such as Temperance Day, National Day, GAR (Grand Army of the Republic) Day and Children's Day. Temperance lectures and workshops were a regular part of each year's program. A four-year program of study was offered under the title of the Chautauqua Literary and Scientific Circle (CLSC). Graduation ceremonies for each CLSC class were held in the Hall of Philosophy, with participants marching under a colorful banner bearing their class year. A program from the 1898 assembly contains a variety of offerings including chorus training, concerts, prayers, roundtable discussions, classes in “Physical Culture and Elocution” and lectures on “The Indians, their Haunts and Homes with Glimpses from Prairie and Mountain,” “The Gold Mine and Miners of Nova Scotia” and temperance. While most of the instruction and lectures were given by local ministers and lecturers, several prominent speakers addressed the crowds at Lakeview over the years, including former president Rutherford B. Hayes in 1892 and African American educator Booker T. Washington in 1896.

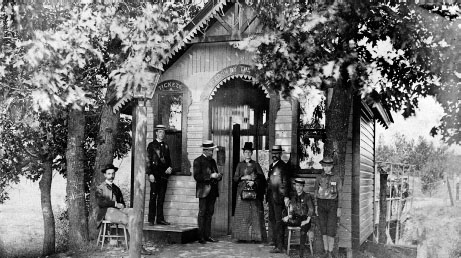

Ticket booth at Lakeview.

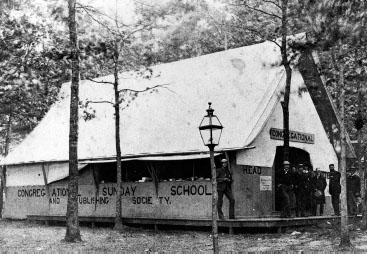

Congregational Sunday school tent at Lakeview.

Outdoor auditorium at Lakeview.

Chautauquans boating on the Sudbury River.

The presentation of such erudite lessons and activities needed an appropriate setting, and over the years the collection of quaint tents and cottages was transformed into a campus of grand halls and spacious auditoriums. The Greek-inspired Hall of Philosophy, dedicated in 1896 and modeled after the Parthenon, stood on the summit of Mount Wayte. An open-air auditorium could comfortably seat five thousand, with room for an additional five hundred people in an adjacent pavilion. Lectures and classes were conducted in the four-hundred-seat Normal Hall. Baptist, Congregational and Methodist social halls were available to those church members who wished to use them. Over one hundred cottages were nestled under the oaks and maples, bearing such nature-inspired names as Sunrise, Oak Dell and Twin Tree. Attendance at the annual meetings began to drop off in the twentieth century, and at the end of the 1917 assembly organizers were scrambling to sell tickets to the following year's events. On November 11, 1918, Armistice Day, the bells at the top of Mount Wayte were rung for the last time, and the property was eventually sold off.

After the sale of the property in 1918, the entire Mount Wayte area fell into disrepair. Many of the cottages burned down or were demolished, and all of the campus buildings were gone within a short time. Today a handful of cottages still stand on Mount Wayte Avenue, some still bearing their distinct Victorian gingerbread decorations. Similar cottages in Oak Bluffs on Martha's Vineyard, also built as part of a Methodist campground, have been designated National Landmarks and a thriving Camp Meeting Association still holds annual summer encampments there. The Chautauqua Movement itself lives on in its birthplace in Chautauqua, New York, where modern pilgrims can still attend a ten-day program of arts, education, religion and recreation. The spirit of the Chautauqua Movement even spawned a short-lived Disney version of the assemblies. In the mid-1980s, then Disney CEO Michael Eisner, inspired by visits to the original Chautauqua near his wife's home in upstate New York, began developing the Disney Institute at Walt Disney World in Florida. Starting in 1996, the Disney Institute offered educational and arts programs at a luxury hotel on the shores of a private lake within the Disney World compound in Orlando. But attendance at the institute never met expectations, and the program was phased out in 2001.

T

HE

“H

OLY

R

OLLER

R

IOT

”

OF

1913

Over the years, the Lakeview site had also been used by various other organizations, including the Salvation Army and the Odd Fellows. One particular group, the Pentecostal Disciples of the Latter Reign, arranged to lease the property for several weeks in 1913 for a camp meeting. The leader of the group was sixty-nine-year-old Madame Maria Woodworth Etter, a Pentecostal preacher and faith healer. Mrs. Etter had spent over thirty-five years traveling the country, holding meetings in tents with crowds of twenty thousand or more. Often, Mrs. Etter's followers, after experiencing the healing power of God, would fall to the ground writhing and speaking in tongues, thus earning the nickname “Holy Rollers.”

The Holy Rollers began their prayer meetings at Lakeview in early August. The meeting had been going on for several days when word spread throughout town that amazing healings and cures were taking place at Mount Wayte. Within no time crowds at the campground grew from two hundred to two thousand, and a near riot ensued. The Framingham Police arrived to break up the crowd and ended up arresting Mrs. Etter and several of her staff on the charge of obtaining money under false pretenses. After posting $300 in bail, Mrs. Etter appeared in the courtroom of Judge William Kingsbury, who would decide whether to pursue the charges against the faith healer.

A parade of witnesses gave testimony for both sides, with many in support of the preacher. One woman who claimed to be a cousin to President William McKinley had traveled all the way from Pennsylvania in order to be healed and testified that Mrs. Etter had restored her ability to walk. Other witnesses claimed to be healed of drunkenness, deafness and muscular ailments. A blind eighteen-year-old Saxonville boy named Joseph Tuttle attended the meeting one night and took the stage in hopes of regaining his sight. Church ministers rubbed Tuttle's forehead, eyes and legs while shouting, “Come out devil, come out!” and “Hallelujah!” When asked by the prosecutor what happened next, Tuttle replied, “Nothing special.” Other witnesses testified that Mrs. Etter had pleaded for money to cover travel expenses, and that her assistants had warned that anyone testifying against her would have the wrath of God come down upon them. Doctors for the prosecution believed that Mrs. Etter used hypnotism to lead her followers into believing that miracles had occurred. After four days of testimony, Judge Kingsbury dismissed all charges and the Holy Rollers left Framingham for good. Maria Woodworth Etter continued preaching until her death in 1924. Today she is regarded as an important voice in the Pentecostal movement of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and many of her writings are still in print.

F

RAMINGHAM AT

P

LAY

There were other ways of passing the time in Framingham that were perhaps less high-minded than the Chautauqua assemblies and Methodist meetings at Mount Wayte. Some preâCivil War attractions soldiered on into the postwar era. Harmony Grove continued as a family-oriented destination for speeches and lectures as well as recreation, although Mount Wayte soon surpassed it in both size and appeal, and the Grove closed in 1877. Its once picturesque grounds were fully redeveloped into rail yards and housing lots by 1900.

Agricultural fairs had always been a staple of entertainment in such a farm-rich town and continued to be so for many more decades. In 1868, the South Middlesex Agricultural Society moved its annual fair to a twenty-four-acre site on the Sudbury River in South Framingham. The event was held over two days each September after the harvest was taken in and was a local institution for nearly fifty years. Framingham was still primarily an agricultural town in the early twentieth century, and the livestock exhibitions and produce displays at the fair were always the main attractions. Horses, hogs, cattle, sheep and poultry were exhibited and judged in the large barns and stables. Prizewinning fruits and vegetables were displayed and sold. Farmers showcased their skills behind the plow in friendly but spirited competitions, and a greased pig chase with the winner taking home the pig was always a hit with the crowd.

The fair also offered a variety of nonagricultural activities over the years, including bicycle and foot races, baseball games between local teams and dog shows. At times the fairgrounds resembled an old-time carnival, complete with sideshow attractions such as giant lizards and a skeleton man. Visitors in 1873 were treated to a balloon ascension by the amazing Professor King.

The highlight of each year's fair was the afternoon of horse racing on the half-mile track. From time to time, the races would feature a head-to-head match between horses owned by two of Framingham's “country squires,” John Macomber and John Bowditch. Macomber owned a 220-acre estate called Raceland on Salem End Road, where he had his own race track installed in 1927 after the fairgrounds closed for good. Horse racing continued at the Macomber track until 1935, when parimutuel betting was legalized in Massachusetts.