Framingham Legends & Lore (18 page)

Read Framingham Legends & Lore Online

Authors: James L. Parr

T

HE

M

USTERFIELD

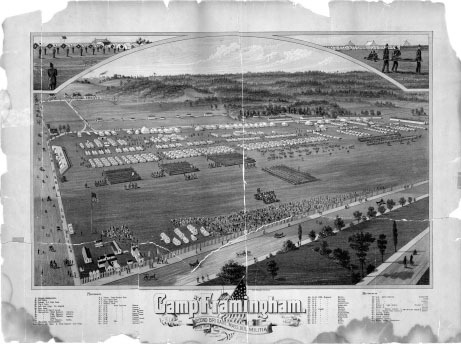

Framingham's central location on the railroad line and Worcester Turnpike, along with its abundance of open land, compelled the state of Massachusetts in 1873 to locate a training ground here for the Massachusetts Volunteer Militia (today's National Guard). State law required each militia unit to spend a week in training, and Framingham's camp was one of several across the state. About 115 acres of former farmland once known as Pratt's Plain situated west of Concord Street and south of the Worcester Turnpike (Route 9) were cleared and developed into the training facility. Several permanent buildings were constructed along Concord Street, including an arsenal, magazine and commandant's house and barn. The fields that had been farmed for nearly two hundred years were graded and cleared for a parade ground. The first militia units arrived at camp on August 7, 1873. The facility was originally called Camp Henry Wilson, after the Natick cobbler who became Grant's vice president, but over the years it took on new names with each new muster of soldiers. Eventually townspeople began referring to it simply as the Musterfield.

A typical encampment lasted one to two weeks. Volunteers would spend that time with their unit marching, drilling and training. The soldiers were housed in white tents that were pitched in perfect lines across the open fields of the camp. Often units would participate in war games and maneuvers in the forests on the north side of town. Nathaniel Bowditch, brother of the Millwood Hunt Club's John Bowditch, often made the vast lands surrounding his “Lilacs” estate available for the exercises, even moving his large herd of prize cattle off of their pasture to accommodate the military.

Residents of the town were often invited to watch parades and drills. A one-day pass would allow visitors to watch inspections, cavalry formations, rifle demonstrations and reviews. The highlight of each summer's encampment was Governor's Day, when the sitting governor of Massachusetts would visit the camp to review the troops. For many years, the governor was chauffeured from the train station to the camp by resident Daniel Cooney in his horse-drawn open carriage.

The arrival of the governor at the Musterfield would be signaled with a salute of seventeen or more guns. Crowds as large as five thousand joined the state leader in watching the day's activities. Events included cavalry parades, band concerts, shooting contests, formal parades and even wrestling. As many as two thousand soldiers would participate in the festivities, representing various militia divisions including cavalry, infantry, ambulance corps, signal corps and artillery.

Bird's-eye view of Camp Framingham, 1885.

Courtesy of Framingham Public Library

.

Regimental colors, Camp Framingham.

Encampment at Camp Framingham.

The military pomp observed at the Musterfield was not reserved only for celebrations and festive occasions. In 1887, residents were witness to one particular military ceremony of great sadness and poignancy. Private Denis Donovan of Boston had drowned in Learned's Pond after going swimming on a hot July day. A few days later, his fellow soldiers escorted his flag-draped coffin down Concord Street to a waiting train while softly singing “Nearer My God to Thee.”

The summer encampments were interrupted only when the Musterfield was used as a staging area for militia units preparing for war. Soldiers gathered in Framingham in 1898 for the Spanish-American War, in 1916 for the Mexican border conflict and again in 1917 for World War I. The final encampment took place in the summer of 1919, ending an almost fifty-year-old Framingham tradition.

A

IRMAIL AND

A

SPARAGUS

The wide, flat parade ground of the Musterfield property was put to a new use in 1920 when the U.S. Army Air Service established an airfield there. Although in operation for only a few years, the airfield was the site of several interesting and exciting aviation events. Commercial aviation was so novel at the time that the public eagerly anticipated and reveled in any and every episode involving planes and pilots.

Perhaps the most historic event at the airfield was the first airmail delivery to New England, in October 1921. Lieutenant Reuben Curtis Moffat piloted a plane from Washington, D.C., to Framingham, carrying mail that was then delivered to Boston by truck. The delivery of a more unusual cargo a few months later made headlines across the country, demonstrating the public's insatiable hunger for all aviation-related news.

On May 17, 1922, a group of more than fifty reporters, photographers and curious residents assembled on the airfield anxiously awaiting the delivery, by plane, of a shipment of asparagus from New Jersey. Included in the waiting crowd were representatives of the governor and the commissioner of agriculture, who had promised both Governor Channing H. Cox and Boston Mayor James Curley a side dish of fresh asparagus on their tables at lunchtime. When the scheduled landing time of noon had come and gone with no sign of the plane, officials at the airport became nervous that something had gone wrong with the flight. Minutes turned into hours and the aircraft and its precious cargo had still not arrived. Finally, at three-thirty, the plane was spotted in the skies south of Framingham and the remaining crowd let out a cheer. But their excitement quickly turned to confusion and concern as they watched the plane turn and head east to Boston. Two quick-thinking pilots on the ground saved the day by hopping into their own planes and flying after the errant asparagus, directing the New Jersey pilot to a perfect landing on the old Musterfield.

Several months later, a pilot and his passenger were killed as they tried to land on the airfield. On July 22, Harvard medical student and pilot Zenos Miller, along with his brother Ralph and friend Dr. Clarence Gamble, took off from Framingham on the first leg of a cross-country flight to California. The plane was circling the airfield when it unexpectedly went into a spin and crashed in a fiery explosion in the swampy area adjacent to the landing strip. Several pilots on hand pulled the men from the flames, but Zenos Miller and Dr. Gamble both died. (Ralph Miller suffered only minor injuries.) For many years after the crash, neighborhood boys would explore the area for the wreckage of the plane that local legend held was still submerged in the swamp.

Routine activity at the airfield consisted of cargo and passenger flights, with barnstorming pilots offering five-dollar plane rides to thrill-seeking passengers. One such pilot was Framingham native Arthur “Ray” Brooks, a World War I veteran who had shot down six enemy planes, earning him the title of “Ace,” as well as the Distinguished Service Cross. Brooks's wartime SPAD XIII plane was restored and placed on display at the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C. Brooks also had the distinction of being the nation's longest-lived flying ace from the Great War, succumbing to old age in 1991 fewer than four months shy of his ninety-sixth birthday.

P

LANES TO

A

UTOMOBILES

A second, more successful airport began operations in the southern part of town in 1929 on farmland owned by Teddy Gould. The official opening of the Gould Farm Airport took place on November 8 and 9, 1930, with almost ten thousand people in attendance. Spectators thrilled to airplane races and stunts, and over seven hundred people took rides, most likely their first ever, in the many aircraft gathered at the event. Over the next sixteen years, various aviation companies offered both cargo and passenger service out of the Gould Farm location. Air shows and meets, as well as demonstrations of military aircraft, were held on a regular basis. All activity at the airfield came to a sudden stop, however, in 1942 when World War II forced the closing of all civilian airports located within twenty-five miles of the coast. After the war, town officials were working on a plan to make the site a municipal airport when Teddy Gould sold the land to General Motors, ending Framingham's almost thirty-year association with the aviation business. GM built an assembly plant on the site, which operated until 1987.

C

AMP

F

RAMINGHAM IN

W

ORLD

W

AR

II

With the closing of the army airfield, all significant military activity on the Musterfield ended. In the 1920s, the Massachusetts State Police took over a portion of the site, where they built their headquarters and a training academy. With the exception of a small staff headquartered in the commandant's house to oversee the remaining buildings and facilities, the rest of the property lay vacant and neglected. The attack on Pearl Harbor and America's entrance into World War II in December 1941 would change all that and create one final chapter in the Musterfield's long military history.

America was a country on edge in the early days of the war, especially in coastal communities, where citizens and local governments worried about possible enemy air attack. Measures were taken to reduce potential targets for German bombers. Blackouts were enforced across Massachusetts. The golden dome of the statehouse in Boston was painted a dull gray to make it hard to find at night. Even large civic gatherings such as Fourth of July fireworks and parades were canceled. In Framingham, the skylights of the Edgell Memorial Library were painted over and an observation post on the roof of the Memorial Building was manned by volunteers who kept watch for enemy aircraft. Other citizens volunteered as air raid wardens to supervise blackouts, and air raid sirens were installed throughout the town. It was in this atmosphere in the spring of 1942 that Framingham residents noticed increased activity on the old campground. Although the work was clandestine, many questions were answered on May 21, when a convoy of trucks and equipment rumbled through town and entered the Concord Street gates. The convoy was made up of soldiers of the 131

st

Combat Engineering Battalion, which had been assigned to Framingham as part of the coastal defense system.

Old and rusting equipment was hauled away as construction began on new buildings. The soldiers were housed in tents for the next six months while more permanent structures were built, including barracks, supply depots, armories, a headquarters building and a base theatre. But these new buildings were not army regulation. Camp Framingham was the site of a camouflage experiment. The entire base was designed and built to look like a typical New England village from the air, in order to fool any enemy pilots who might attack. Soldiers were housed in “barracks” resembling colonial homes; the attached garages were actually shower and latrine facilities. The double chimneys and the shingled roofs were fake. The whole area was landscaped with bushes and flowers so as to blend in with the surrounding neighborhood. The soldiers even strung clotheslines in the “yards,” and would often awake to find some prankster had strung up women's undergarments during the night. The battalion headquarters looked like a school; the theatre was built as a church and was in fact used for religious services for the soldiers.

The soldiers from the 131

st

spent their days inspecting coastal defenses and working on various construction projects. The regimental band attached to the battalion was kept very busy; within a few days of their arrival, they played in the town's Memorial Day parade and were active for the next year and a half, performing at dozens of ceremonies and activities in towns from Marlborough to Boston. The town welcomed the soldiers with enthusiasm and made every effort to make their stay a pleasant one. A servicemen's recreation room set up in the basement of town hall included ping-pong tables and a small library. One hundred soldiers from the camp attended a welcome dance in town hall in July. A blackout had been ordered for the town that night, causing the soldiers and their invited guests to dance by the light of the moon shining through the windows. Each soldier was allowed to bring his own guest, but if he attended alone, the dance committee promised to “supply attractive girls selected by the sponsoring organizations.” Not surprisingly, many romances developed at these gatherings and several weddings between Framingham girls and servicemen resulted.